Pains and Dreams on the Silk Road

Chinese activity in the Middle East has been a lesson in non-involvement and support for local economic projects; yet, as the Belt and Road Initiative kicks off, China’s role in the MENA region will inevitably change.

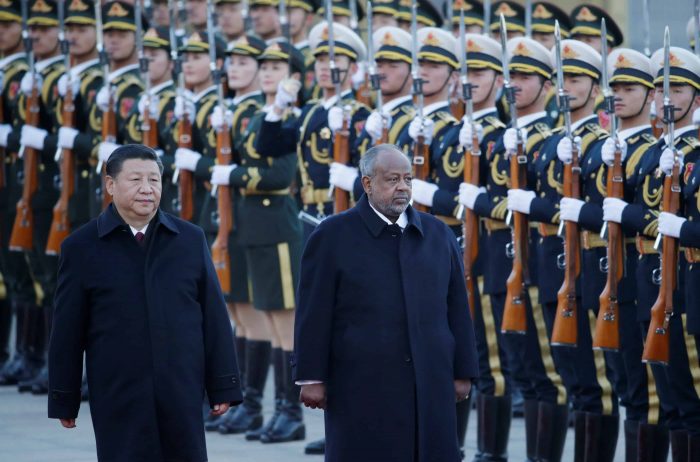

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Djibouti’s President Ismail Omar Guelleh inspect the honor guard during the welcoming ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China November 23, 2017. Jason Lee/Reuters

In 2013, when Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the “Belt and Road” initiative, China and the Middle East rediscovered their common historic legacies and shared memories of the ancient lands and maritime Silk Roads linking Imperial China and the Arab World. Because of policies arising from the Belt and Road initiative, China has taken a deliberate turn to “look west,” designating Eurasia and Africa as its priorities for international cooperation and deal-making.

Today, Middle Eastern oil, natural gas, and markets are crucial revenue sources affecting daily life in China. In 2017, China imported about 200 million tons of oil from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), which was close to half of its total crude oil imports. With its domestic manufacturing market becoming increasingly saturated, China has pinned high expectations on exporting to the MENA region, which boasts 450 million consumers.

By 2017 China had become the largest overseas investor in the Middle East and signed contracts with states across the Arab World that amounted to $33 billion. Sino–Arab trade reached $191 billion that same year while Sino–Iranian trade hit $37 billion. Also in 2017, Israeli trade with China witnessed an increase of 19 percent to reach $12 billion and trade with Turkey hit $26 billion.

Ultimately, many economic and cultural partnerships have been spurred between China and the Middle East. In contrast to Western and Russian heavy-handed military involvement in the Middle East, China has built a substantial economic presence in the region, ranging from construction of seaports, highways, and railways to nuclear power plants, industrial parks, and oil refineries. Chinese banks have also opened branches across the region. While traditional powers perceive the region as a “battleground,” rising powers like China and India regard the MENA region as an untapped market. That’s why the Chinese government has generally sought to practice political neutrality and avoid getting mired in regional politics and conflicts, concerning itself more with possible security threats to its overseas projects and expatriates. Overall, China adheres to a business-oriented and pragmatic foreign policy in the Middle East, in which communist ideology or political advocacy are largely downplayed.

In particular, China has been increasingly creative and innovative in implementing its traditional diplomatic dogmas of the “Four-No” policies with regards to the region: non-interference in others countries’ internal affairs; non-alignment between aligned powers; no construction of foreign military bases; and no political strings attached in offering foreign aid. However, as Beijing’s involvement becomes more far-reaching and intensive in the years to come, China will likely face unpredictable situations where it will be required to slightly bend its four dogmas.

Although China adheres to a “zero-enemy” policy with regards to the Middle East, in recent years it has attempted to engage with Middle Eastern powers militarily in an incremental manner. Yet, while inching toward military engagement, Chinese leaders have kept in sight the goal of enhancing Beijing’s capacity to provide public good to locals in the region in five key ways.

China sent convoy fleets to the Gulf of Aden. From 2009 to August 2018, China has dispatched thirty convoy fleets to the Gulf of Aden and the Somali waters at large. These fleets have visited Port Djibouti, Mombasa of Kenya, Port Sultan Qaboos of Oman, Jeddah of Saudi Arabia, Port Abbas of Iran, Karachi of Pakistan, and other seaports adjacent to the Red Sea and the Western Indian Ocean. The fleets were used to serve the UN World Food Programme ships and help the international commercial ships against pirates, as well as rescue Chinese and other nationals.

China’s military engagement in the Middle East, albeit insignificant and non- institutionalized, indicates that China has an interest in participating in Middle East security governance. Although it has shied away from military affairs due to its non-interference principle, Beijing is exploring feasible and legitimate ways for its military to play a positive role, a breakthrough of its “Four-No” policies.

China has built a logistics base in Djibouti. For a long time, Beijing was opposed to building foreign military bases in the Middle East, claiming that the bases’ presence may worsen the security dilemma and even invite proxy wars among Arab countries. In May 2015, however, Djibouti President Ismail Omar Guelleh announced that China was in talks regarding the establishment of a military base in the northern Obock region of the country, implying that the new Chinese base is to overlook U.S. military installations there. The base was officially opened in August 2017 by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy.

Yet, to provide a favorable political environment for Beijing’s first overseas logistics base—which in essence goes against China’s anti-foreign military base policy—China has actively participated in the construction of Djibouti’s free trade zone, which covers 48 square kilometers. The initial investment for the project was around $340 million. As of August 2018, the China-funded free trade zone of Djibouti was completed.

Also, along with the construction of the base, China built the Port of Doraleh, a multipurpose port with a total investment of over $590 million. The port was financed by the Hong Kong conglomerate China Merchants with a total of $185 million and by the Export-Import Bank of China.

China is increasing interest for arms sales to the MENA region. Compared to the United States, the European Union, and Russia, China’s arms sales to the Middle East are not significant. In 2012 for instance, China’s arms sales to the region only reached $753 million, while those of the Barack Obama administration were as high as $28.5 billion, according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. However, there have been signs of increasing minor arms sales between China and the region despite China’s zero-enemy policy. Turkey, for example, declared in September 2013 that it would purchase China’s FD-2000 missile defense system, which defeated other arms manufacturers in a bid, with a sale price of only $4 billion. The Turkish government finally had to suspend the transaction due to U.S. opposition. The United States opposed this planned purchase because were Turkey to buy from China, the new purchase would put an end to the monopoly of Western arms dealers’ selling to the NATO member. Besides Turkey, in recent years, the Gulf countries, such as the United Arab Emirates and Iraq, were interested in China’s “Pterosaurs-1,” an unmanned aerial vehicle capable of carrying BA-7 and YZ-212 missiles.

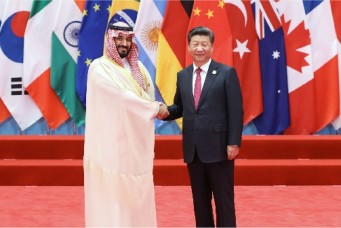

China is performing joint military rehearsals in the region. In recent years, China has sent more and more military delegations to the Middle East and carried out several joint military rehearsals. For instance, China held joint military rehearsals with Turkey in 2010, with Saudi Arabia in 2016, and with Iran in 2017. Moreover, China and Russia had several military exercises in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Despite China’s inability to project hard military power in the area, the exercises are signs of Beijing’s soft military footprints in the MENA region.

China is participating in the UN peacekeeping operations in the Middle East. In September 2015, President Xi attended the UN peacekeeping summit in New York, declaring that China would build eight thousand UN standby peacekeeping forces, representing about 20 percent of the world’s total. He also stated that China would donate $1 billion to the UN for its Peace and Development Fund and that China would train two thousand peacekeeping troops for other UN member states. As of April 2018, China has contributed over eighteen hundred soldiers and police to the UN peacekeeping missions in or near the MENA region. China’s police and troops have taken part in five UN peacekeeping missions in the area: Western Sahara (MINURSO, ten persons), Darfur of Sudan (UNAMID, 371 persons), Lebanon (UNIFIL, 418 persons), South Sudan (UNMISS, 1,056 persons) and Palestine-Israel (UNTSO, five persons). China wants to show the world that Beijing is willing to fully embrace multilateralism and do its duty as a responsible power, which forms a sharp contrast to the U.S. government’s unilateralism and populism.

China’s New View

The Middle East and North Africa is at the converging points of modern-day silk roads connecting Europe, Asia, and Africa. The MENA countries are China’s natural business and political partners. China has never colonized any part of the Middle East, nor has China any historical burdens in developing friendly and mutually beneficial relations with MENA countries. Beijing’s “non-alignment,” “no sphere of influence,” and “no proxy” policy will give China an upper hand in its rivalry with other global powers active in the region. That said, rising from a regional to a global power, China will inevitably encounter its “growing pains” regarding its engagement with the area.

For example, China’s non-alignment policy cannot bring it authentic friends. Also, China’s huge investment in the region may add fiscal burden to the countries that accept this investment. China finds it hard to implement its mediation diplomacy between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and between Palestine and Israel. China lacks clear-cut proposals for conflict resolution in Syria, Yemen, and Libya.

However, China’s economic, political, diplomatic, military, and cultural engagements with MENA will enhance Beijing’s capacity to participate in the region’s governance. Ultimately, China and Middle East countries will establish a closer partnership, linked by the Belt and Road initiative.