Speed Bumps on the Silk Road

China has unveiled a “win-win” policy paper to guide its approach to the Middle East. Its $1 trillion One Belt One Road infrastructure initiative will extend all the way to North Africa. But can trade buy Beijing political clout in the region?

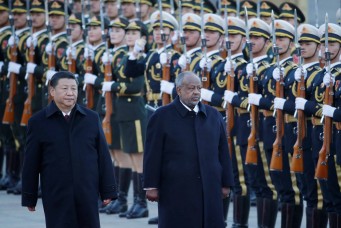

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Saudi Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman Bin Abdelaziz Al-Saud at G20 summit, Hangzhou, Sept. 4, 2016. Ma Zhancheng/Xinhua/ZUMA

China released its first-ever Arab Policy Paper in 2016, detailing the official government approach to the Middle East. “Friendship between China and Arab states dates back to ancient times,” the paper begins. It speaks about the land and maritime Silk Roads linking Imperial China and the nations to its west. Quickly, the paper pivots from the distant past to the immediate present, invoking Beijing’s foreign policy mantra: “Learning from each other, mutual benefit, and win-win results.”

“Win-win” is the official guiding framework for Beijing’s relations with the rest of the world. It is meant to set China apart from the perceived lingering colonialism in the foreign policy of Western nations. It stresses mutual benefit while respecting every country’s sovereignty and right to self-governance. It shuns military brandishing (notwithstanding its current maneuvers in the South China Sea) and emphasizes economic deal-making.

A nice slogan will not be enough for Beijing to pack greater influence in the resource-rich, politically unstable Middle East. For perhaps understandable reasons, China is unwilling to challenge American and Russian power in the region. China lacks the military might to engage in prolonged combat operations in the Middle East. It has no military presence in the Gulf or the Indian Ocean, rendering it incapable of any meaningful projection of hard power. Nor has China been willing to use its position on the international stage to influence political developments in the region, even as its failure to build diplomatic credibility in the Middle East undermines its larger objective of achieving great power status.

The turmoil unleashed by the Arab Spring presented Beijing with a challenge and an opportunity to reconsider its studied neutrality and take a more assertive posture. The People’s Liberation Army sprung into action to evacuate some thirty-five thousand Chinese workers stranded by the civil war in Libya. As Enrico Fardella of Beijing University has noted, with conflict also raging in Syria and Iraq, influential voices within China began to agitate for at least “a system of prevention” and “constructive intervention” aimed at safeguarding Chinese interests and Chinese nationals abroad.

Yet little in Beijing’s cautious approach has changed, to the consternation of many in the region who would like to see China’s influence, especially as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, put to constructive ends. “I don’t even need to explain that human rights—including the most basic one, the right to life—means nothing for Beijing,” wrote a commentator in the Turkish daily Hürriyet in 2012, unleashing fury after China vetoed punitive measures against Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad. “This is simply a mercantilist dictatorship without any principles.” At the same time in the Saudi-owned daily Asharq Al-Awsat, a commentator called China “an economic giant but a political dwarf.” In international politics, the writer went on, “China’s image reminds one of the Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland, fading away behind an enigmatic smile. Name any issue and you are unlikely to find a coherent Chinese position. In the United Nations Security Council, China seldom goes beyond cryptic and confusing statements.”

Bandung and Beyond

After China’s Communist revolution in 1949, Beijing took an assertive role in the Middle East, in support of anti-colonialism. It was a force at the 1955 Bandung Conference hosted by Indonesia, which brought together twenty-nine countries from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East to denounce colonialism as “an evil which should speedily be brought to an end” and lend support to Arab liberation struggles; the gathering inspired the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement six years later.

China took a keen interest in the Middle East for a variety of reasons. It sought diplomatic recognition in its campaign to displace the Republic of China (now Taiwan) as the sole legitimate government of China in foreign relations between countries and admission to the United Nations. Chairman Mao Zedong also feared that control of the Middle East by a hostile power, whether it be the United States or the Soviet Union, would threaten China’s national security. In addition, China was intent on showing support for Muslim causes in order to bind China’s own Muslim population to Beijing’s rule. Besides initiating trade relations with Arab countries, Beijing supported Arab national liberation movements. In 1956, President Gamal Abdel Nasser made Egypt the first Arab and African country to recognize the People’s Republic, and Beijing in turn provided diplomatic and financial support to Cairo amid the Suez Crisis—the tripartite invasion of Egypt by Israel, France, and Great Britain.

But China’s political overtures have generally failed to resonate with Middle Eastern countries. For their part, as Kurt Radtke of the International Institute for Asian Studies in the Netherlands has explained, Chinese Communists explicitly rejected the kind of feudal, patriarchal, or religious political culture found in much of the region. Arab countries in turn were left unimpressed by China’s relative lack of military and economic power prior to the 1970s. Today, political relations remain tied by many of the principles adopted at the Bandung conference, such as abstention from intervention, interference, or exerting pressure in the affairs of other countries. Beijing, for example, does not pressure Arab states to democratize or reform. The Arab Policy Paper lays out Beijing’s current ideological synergies with the Middle East: “Safeguarding state sovereignty and territorial integrity, defending national dignity, seeking political resolution to hotspot issues, and promoting peace and stability in the Middle East.”

Oil and Arms

Trade remains at the center of China’s relations with the Middle East. After China opened its economy for international commerce in the late 1970s, trade and energy security became the foundation of its foreign policy. China and Middle East nations have reached lucrative deals encompassing oil, infrastructure, and arms.

The Middle East is currently China’s second-largest supplier of crude oil and seventh-largest trading partner. Trade between Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states and China reached $92 billion in 2010 and is projected to hit $350–550 billion by 2020. To hit that target, China envisions a “1+2+3” development of economic relations with the region. The core will continue to be energy cooperation. Infrastructure construction, trade, and investment will be layered on top, and nuclear energy, space exploration, and new types of energy will be the third phase. The project that encapsulates all three of these areas is the One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR), a $1 trillion infrastructure development initiative led by China that will span East Asia to North Africa. From Beijing’s point of view, OBOR is critical to securing its energy supply in the Middle East and Central Asia and opening new trade routes should current supply channels through Asia be compromised.

Though it is searching for alternative energy sources as part of a larger drive toward improving environmental sustainability, China’s oil consumption is nonetheless projected to grow over the next decade. The country’s consumption in 2010 was 9.57 million barrels a day (5.5 million of which was imported), second only to the United States. By 2020, China is expected to import 70 percent of its oil needs from the Middle East—5.9 to 6.9 million barrels a day. By 2025, China’s demand for oil will increase by another 30 percent, to 12.8 million barrels a day.

Each Middle Eastern country has received its own share of this demand from China. Saudi Arabia is China’s largest Arab oil trading partner, providing 17 percent of the country’s oil imports. As demand from the United States continues to fall, China is also emerging as the largest importer of Saudi oil, averaging well above 1 million barrels a day over the last few years. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), China’s second-largest trading partner in the region, registers comparatively modest oil exports to China but is determined to increase that volume. PetroChina, the third-largest oil and gas company in the world and a subsidiary of the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), has incorporated nearly twenty companies in the UAE in less than five years.

Iraq is China’s third-largest Arab trading partner, after Saudi Arabia and UAE, providing 10 percent of Beijing’s oil imports. In 2014, China purchased nearly a third of the oil that Iraq produced that year and was the country’s largest oil customer. The CNPC and China National Offshore Oil Corporation have contracts with the Iraqi government to develop oilfields in Rumaila, Halfaya, Al-Ahdab, and Missan. Iran, meanwhile, is China’s third-largest oil supplier, providing 11 percent of China’s oil imports by 2009. Zhuhai Zhenrong Corporation, a Chinese state-owned oil company, signed a twenty-five-year deal in 2004 with Iran to import 110 million tons of liquefied natural gas.

To strengthen its ties to Middle Eastern nations and facilitate the trade in oil, China has maintained a long-term policy of supplying arms to the region. Since 2005, Iran has been one of China’s biggest customers, accounting for 14 percent of its military exports. From 2006 to 2011, China sold Iran $312 million in arms, second only to Russia’s $684 million. China has similar arrangements with Algeria, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq. In turn, these countries offer Beijing economic concessions in the form of equity stakes in oilfields as well as other natural resources and precious metals.

With the global diversification of energy portfolios and resulting drop in oil prices over the past five years, the Middle East has been looking to expand its trade with China into areas outside of oil and defense. Chief among these is construction and infrastructure. Following the 2003 American-led invasion of Iraq, China took a discount on contracts with the Iraqi government for reconstruction, even building its own airports to provide transport for Iraqi oil workers. The Economic Cooperation Organization, comprised of Central Asian countries and Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey, established a rail link between Iran and Kazakhstan that connects with China. Another new rail project led by China Railway Construction Corporation Limited transports Muslim pilgrims from around Saudi Arabia to the annual Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca.

Egypt is one of only five countries on the African continent to have a special economic zone with China. In 2012, Chinese–Egyptian trade reached $9.6 billion, though the growth rate of the trade deficit (in favor of China) reached 16.2 percent between 1995 and 2012. During his 2014 visit to Beijing, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi signed a strategic partnership with China for cooperation on technology, economic development, new and renewable energy, and space exploration. Chinese–Egyptian trade reached $11 billion by the end of 2014.

The UAE similarly uses free trade zones to facilitate its trade with China. There are roughly thirty-nine hundred Chinese companies in the UAE, nine hundred of which are registered in these zones. As a result, despite being China’s second-largest trading partner in the region, it is nevertheless China’s hub for business dealings with the Middle East, Africa, and even Central Asia. Because trade between China and the UAE in oil is comparatively low, other goods account for overall volume. China exports manufactured goods such as textiles, electronics, machinery, and solar panels to the UAE while the UAE exports natural gas, merchandise, and services. Emirati companies are also making headway in China. Dubai Ports World, for example, has been managing property construction projects, hotels, and ports in China.

Despite the progress, the China–Middle East trade corridor remains relatively quiet compared to those with China’s other trading partners. China and the Middle East differ on the extent to which the current situation is a “win-win.” While China sees much potential and little downside in the status quo, its Middle Eastern counterparts are more skeptical of the economic gain and wary of China’s official positions on the geopolitical stage.

One issue is that China has a history of exporting its own labor to execute projects in the Middle East, even to the point that the Chinese violate local labor laws protecting local workers. The state-owned enterprises running these projects have lagged behind in market competitiveness, leading to neglect in cost control. In 2004, six GCC states sent their finance ministers to Beijing to negotiate a Framework Agreement on Economic, Trade, Investment, and Technological Cooperation governing the establishment of free trade zones with China. Although seven rounds of negotiations have taken place, there is a lack of urgency of both sides since neither views the other as a crucial economic partner in the short or medium terms.

Another factor holding back trade is China’s search for alternative energy providers, particularly in North America, after having lost tens of billions in investments due to the conflicts in Libya and Syria. Chinese trade officials told their Arab counterparts at an energy cooperation forum in Beijing in late 2016 that they had to diversify their economies and offer more than energy exports if they wanted to expand their trade relationships with Beijing. Even though the Middle East has been explicitly diversifying its exports, China’s message was clear: there is still much to be done, and there’s only so much China can do to support those efforts in the early stages.

Lost in Translation

Historically, China has been confused by the disunity in the Middle East, dating back to the inability of Arab states to form a common position on Palestine after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. China tends to judge the region’s issues in isolation, rather than in consultation with relevant Arab stakeholders. The lack of engagement and understanding about local dynamics ensures a degree of distance between China and its Middle Eastern partners. It practices neutrality to avoid getting mired in regional politics and conflicts, yet blatantly plays Middle East countries off of one another to maintain advantageous positions. For example, China supported both Iraq and Iran during their 1980–88 war and continues to be on both sides of the UAE-Iran dispute over islands in the Gulf.

Writing in 2011 in the International Herald Guidance, a Chinese foreign policy journal published by the Xinhua News Agency, researchers Liang Jiawen and Zhang Bingyang argued that when it comes to the Middle East, China’s policies are “accepted by all parties, but fail to satisfy any one party.” There is no sign that China will abandon that neutrality in the foreseeable future. Not only is China unable to project hard power in the Middle East due to a relative lack of military capacity, Beijing values working within the Western order and prefers to influence international governance institutions with its economic clout.

Yet Beijing does have options for upgrading its standing in the Middle East. One is to improve conditions for the twenty-five million Muslims in China, whose mistreatment by the Communist regime, which officially promotes atheism, angers many in the Middle East. In 1982, the government promulgated Document 19, which discourages the building of new religious structures and brought all existing structures under the Bureau of Religious Affairs. The move exacerbated the conflict in Xinjiang province in western China, where Uyghur separatists are demanding independence from what they consider Chinese occupation.

In 2005, a survey conducted by the Arab American Institute indicated that 15 percent of Egyptians and 41 percent of Saudis held unfavorable views about China. By 2011, the unfavorable ratings increased to 43 percent and 66 percent, respectively. China detractors range across the spectrum from Islamists to militants to more moderate sections of the Arab population. After the Arab Spring, then-Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi expressed disgust at China for backing Arab dictatorships, particularly China’s veto of a UN resolution for action against the Syrian regime. Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, has also singled out China for abuse. He called on China’s Uyghur minority to join the jihad against infidels.

Beijing can also improve perceptions of China in the Arab World through extensive cultural and academic exchanges and the facilitation of tourism. China has been slow to establish Arabic-language satellite television channels to reach Arab households. China publishes one Arabic-language magazine, Jinri Zhongguo, and it is distributed only in Egypt.

Finally, China can cultivate its soft power in the Middle East by ensuring that its economic activities do not lead to exploitation and resentment. GCC nations are concerned that the flood of cheap Chinese manufactured goods will lead to an economic form of colonialism and retard the development of local industries. The violation of local labor and environmental protection laws by Chinese-operated firms is another source of resentment. Given the centrality of trade in China’s relations with the region, addressing such concerns will be critical to Beijing’s outlook for winning long-term influence in the Middle East.

Rebecca Liao is vice president of business development and strategy at Skuchain. She served as a foreign policy advisor to Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Financial Times, Foreign Affairs, Atlantic, and Dissent, among others. On Twitter: @beccaliao.