The Gulf’s Global Moment

A major business deal tests the aspirations of Gulf business leaders.

A KFC restaurant in Fujairah, United Arab Emirates, Feb. 22, 2008. Basil Soufi/Wikicommons

The $2.5 billion deal announced earlier last month that a Dubai-based consortium of investors will acquire Americana Group, one of the world’s largest food and franchising conglomerates, is important in ways that transcend finance. The acquisition is a crucial test for the Gulf’s business environment at a time of deep economic uncertainty brought on by weak oil prices and real estate market.

Americana Group, a Kuwaiti corporation, operates across the whole Middle East, and in parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe. In addition to employing thousands of people, it has a global logistical infrastructure. Large networks of businesses (comprising thousands of medium-sized companies) revolve round its operations. And it is a major taxpayer in many countries.

For few years now, Americana Group has not been at the height of its performance. This means that the consortium acquiring Americana believes it is able not only to manage such a complex global behemoth, but lead a needed operational transformation. But the acquiring consortium, headed by Emaar’s chairman Mohamed Alabbar, is neither a leader in Americana’s industries, nor is it a private equity firm, supposedly, with the skills to effect a transformation. This demonstrates the confidence and self-belief that many Gulf investors, increasingly, have. They are convinced that the success many Gulf companies have achieved, in the last fifteen years—for example in real estate, hospitality, retail, logistics, and aviation—has given them sufficient experience to lead and transform global businesses.

Two factors strengthen that belief. The first is the availability of funding. Despite the decline in oil prices to less than a third of its height in 2007/2008, cash inflows to most Gulf economies have remained strong, and importantly, concentrated within relatively small networks of ultra-high net-worth merchant families. And so, relative to many global investors, especially in the U.S. and Europe where low-growth and austerity have taken their toll, leading Gulf investors have a comparative advantage in mobilizing and securing funding. As the old dictum goes: cash is king, especially in boosting confidence.

The second factor is that the Gulf has indeed made impressive strides, not only in business management, but more importantly, in attracting—and increasingly nurturing—talent. Many business (and political) leaders in the Gulf believe that their and their principal skills, experiences, support systems, and exposure, enable them to compete with the best in the West.

For thirty years now, the Gulf has been on an upward trajectory. Economically and in most living standards metrics, the Gulf has by far surpassed the rest of the Arab World, to the extent that Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries no longer measure their economic progress against that region. The Gulf’s ruling political-economy circles have also been expanding their holdings (and influence) far beyond North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. But what’s new here is the business mindset that believes that the “Gulf has arrived at its global moment”, as one of the Gulf’s most prominent thinkers recently put it to me.

However, that “moment” comes at a time when large constituents in the West are increasingly not only wary of Arab and Muslim presence, but hostile to it. Already, several Gulf-led bids for major economic assets in the U.S. and Europe were thwarted on “national security” grounds. Despite its international presence, Americana is controlled by the Kuwaiti Al-Khorafi family. The deal to acquire it will, largely, be determined in the Gulf. But the more GCC economic actors pursue global assets, the stronger the barriers that will be erected against the region’s ambitions.

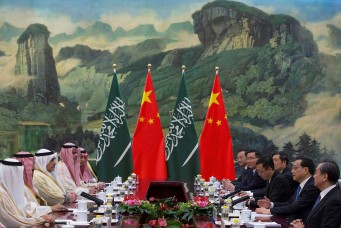

This will drive some in the Gulf to look east to Asia, where economic growth is more promising than in the West, and where political apprehension of Arab ownership isn’t pronounced. Despite the growth and the young demographics, Asia continues to lack the global brands that many emerging-market investors covet and, broadly speaking, the technology and best practices that attract international capital. Almost inevitably the Gulf’s economic expansionism, especially when it goes after top-tier assets, will trigger political opposition and trade tensions.

The Gulf’s record as owners of global businesses will either vindicate or doom its ambitions. As leading Gulf power centers assume conspicuous and active managerial roles in global businesses, they will have to gradually prove themselves desirable investors, and so subtly lessen the apprehensions against Arab and Muslim money. Or their rise will be marked with inexperience and over-confidence, which could add another layer of foreboding towards Arabs on the global stage.

Tarek Osman, a political economist and broadcaster focused on the Arab and Islamic worlds, is the author, most recently, of Islamism: What It Means for the Middle East and the World.