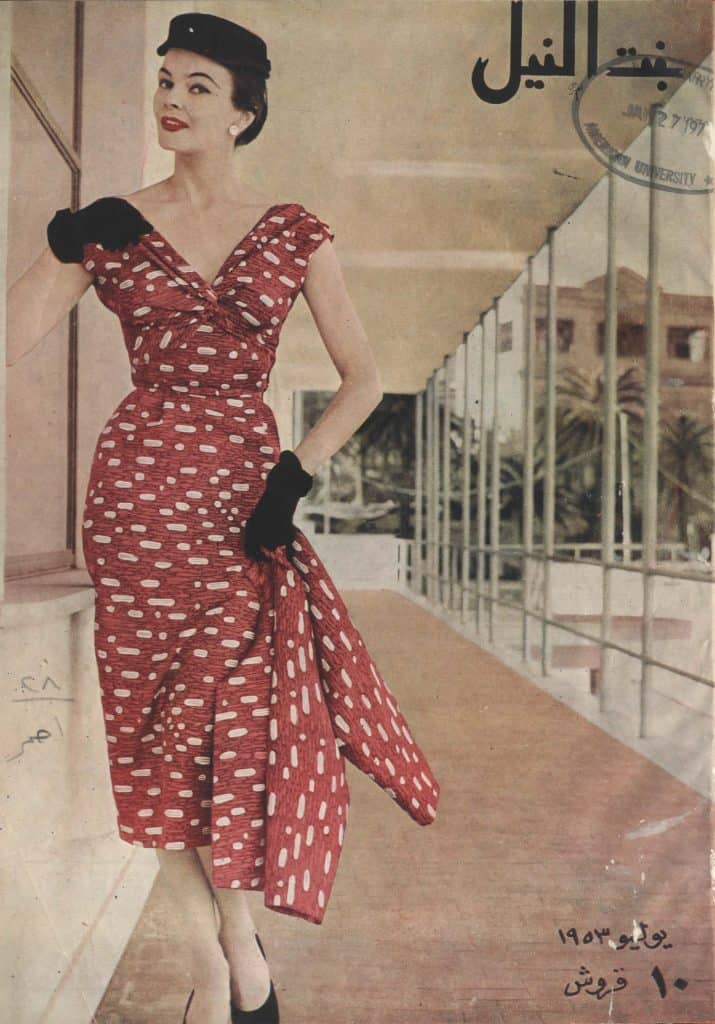

Daughter of the Nile

A profile of Egyptian feminist and founder of Bint Al-Nil journal Doria Shafik.

Doria Shafik. Courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library/Van Leo Collection

Doria Shafik, Egypt’s best-known feminist and suffragette, started the women’s journal Bint Al-Nil at a low point in her life. She wanted to counter the public’s image of her as being “too French.” As editor-in-chief of La Femme Nouvelle, a Francophone culture magazine, Shafik was often associated with its publisher Princess Chevikar, the vengeful and publicly hated divorcee of King Fouad of Egypt. This association caused Shafik to be excluded from the Egyptian Feminist Union and regarded as one of Chevikar’s opulent “ladies of the salon de thé”—a tea-sipping detached elite, removed from the suffering of common Egyptians. Moreover, Shafik was bored with her job as a French-language inspector in the Education Ministry, and was frustrated with the limited progress made on women’s rights in her country. Her burning desire was to enter public life. To her, journalism was the gateway into that world.

The glossy Arabic-language Bint Al-Nil journal appeared on newsstands in November 1, 1945. It sold out within the first two hours, and did not stop circulating until 1957, when the government forced its closure. With a name derived from Shafik’s own self-identification as the “daughter of the Nile,” the purpose of the journal was to awaken Egyptian and Arab women to the women’s rights movement.

Looking through the select articles of the journal made available by the American University in Cairo, one encounters an archetypical lifestyle magazine, featuring motherhood tips, philanthropic news and profiles of celebrated women in history, but the occasional dip into activism is hard to miss. Shafik used Bint Al-Nil as a platform to broadcast her radical feminist voice and promote better conditions for women.

The magazine successfully turned heads at a time when the women’s movement was buried in the heightened nationalism that marked the run-up to the Gamal Abdel Nasser-led revolt against the British and the ruling monarchy in 1952. Close reading reveals the evolution of Shafik’s own intellectual thought and entrance into public life, which led her to some of the most profound feminist undertakings in her lifetime and in the Egyptian suffrage movement.

The journal also raises questions about the difficulties of generating a feminist discourse within a culturally impenetrable and patriarchal society in a country that gave women the right to vote only in 1956. As the editor, publisher, and owner of Bint Al-Nil, Shafik faced such challenges head-on. The first such challenge came from within the publication. In the first two years of Bint Al-Nil, Shafik’s editorial partner, Ibrahim Abdu, toned down her language in her editorials after they had been translated from French in order to avoid the “Al-Azharites’ immediate wrath and violent opposition to Bint Al-Nil.” At the time, Abdu claimed that Al-Azhar—Egypt’s top religious body—was strongly against women entering the same workforce as men. Aware of the mounting opposition to her project, Shafik fought hard to maintain editorial and financial independence.

By 1949, four years after the journal’s launch, Shafik was fighting criticism from the public and the press that she was inciting women to ignore their domestic responsibilities and engage in politics. Three times during the span of a year, she churned out editorials defending her publication’s mission and identity, arguing that it was neither a political organization nor did it aim to embolden women against religion. In the May issue of 1949, Shafik maintained that the magazine only hoped to encourage women to fight for their political rights. That women’s lack of political emancipation was at the core of their oppression pervaded Shafik’s feminist thinking.

In another editorial, she scoffed: “What will our men in Paris say when they are asked about the status of women in political life? Do they say they are at its bottom? […] Or do they say that they are at its zenith but are not equal to an illiterate carpenter or shoemaker who can fingerprint the ballot.” She signs off the piece with a call to parliament to grant women suffrage.

Understandably, Shafik was locked in a fight with the public, whose antagonism toward her was deepening. As she intensified her efforts to bring women political and social rights such as curbing one-sided divorce and polygamy, her foes multiplied. In 1948, when she created a union named after the journal, she came under attack from the clergy, conservatives, and progressives alike, and even the older generation of feminists, who were students of famed feminist Huda Al-Shaarawi. Although Shafik’s feminism reconciled Islam with equality and modernity and aimed to reconceive public life for women through political participation, her beliefs were hardly tolerated.

Against this backdrop, Shafik’s political consciousness radically shifted from a bourgeois understanding of women’s rights to a more class-conscious, and later militant, kind of feminism. By the early fifties, Shafik began to enter the political fight, Marxist lawyer Loutfi Al-Kholi, who was involved in the work of the magazine, noted. “She transformed Bint Al-Nil into a movement that related the liberation of women to the larger political struggle,” he is quoted in Cynthia Nelson’s biography of Shafik as saying.

In February 1950, an intensity emerged in Shafik’s writing. In an editorial addressed to the Egyptian prime minister, she writes with incisive irony: “Why are we doubting the prime minister’s words? Didn’t His Excellency, Mustafa Al-Nahas, announce last summer that the Wafd [Party’s] primary goal was to grant Egyptian women the right to vote?” It was time to change tactics, she added—“to assail men, surprise them right in the middle of injustice, that is to say, under the cupola of parliament.” Her bold words hinted at a major protest that she was planning.

In the afternoon of February 19, 1951, Shafik, along with 1,500 women, stormed parliament. They held a four-hour demonstration before being received in a parliamentary office and extracting a promise from the president of the senate to take up their demands for suffrage, amendments to the personal status law, and equal pay with men. Although a draft bill was in the pipeline, the prime minister blocked shepherding it through parliament.

Shafik stood trial for staging the sit-in, and her case was postponed indefinitely. Then, after a group of army officers calling themselves the “Free Officers” took over the country in July 23, 1952, things slightly looked up: Shafik praised the new rulers and wrote that they would herald “the beginning of a renaissance” for women. But the officers’ authoritarian bent soon became apparent, and in response to the lack of female representation on the constitution-writing committee, Shafik held a hunger strike.

Lasting for ten days, the strike turned Shafik into an international figure and earned Egyptian women a written promise by the government for full political rights. However, the 1956 constitution granted women only vaguely-worded political rights on the condition of literacy. Unassuaged, Shafik headed an all-out confrontation against Nasser, protesting in the Indian embassy and holding a “hunger unto death” strike against what she viewed as his dictatorial rule. Nasser himself ordered Shafik’s house arrest and banned her publication. Shafik withdrew into an eighteen-year period of seclusion before allegedly throwing herself off the balcony of her apartment.

Shafik’s solitary demise was shocking for a woman who had pioneered feminist consciousness-raising and championed women’s suffrage and advancement for many years. Her publication and organizing are key to Egyptian women’s emancipation even today. Finding solace in poetry during her final days, Shafik reflects on her broken legacy and the lone march ahead: “My name begins with a D/and I am a woman…Daughter of the Nile/I have demanded women’s rights/My fight was enlarged to human freedom/And what was the result?/I have no more friends/So what?/Until the end of the road/I will proceed alone.” But it is only after her death that Egypt began to mourn the loss of Shafik and understand the sacrifices she has made for feminism.