Locked-in Emissions: The Climate Change Arms Trade

With militaries’ locked-in fossil fuel systems and looming climate chaos, the arms industry continues to take advantage of nefarious profit opportunities.

An unexploded missile is seen in a field off the road outside Maarat al-Numan, Syria, Jan. 30, 2020. Omar Sanadiki/Reuters

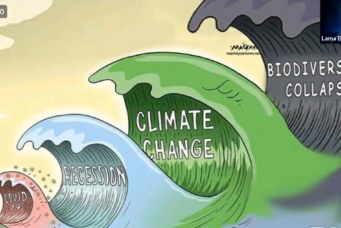

The consequences of climate change threaten the survival of the planet, with people in poorer countries being the first and worst affected. For some, however, climate change is yet another opportunity to make money. With new wars and internal armed conflicts a projected consequence of the increased scarcity of arable land and fresh water, continued competition over fossil fuels, the development of a new market of “green” arms, and border militarization to inhibit climate refugees, the arms industry is bound to profit from the climate crisis. The exclusion of the military from international emission reduction targets and growing global military spending further accelerates this process.

The continued dependence of Western militaries on fossil fuels makes the Middle East an important customer of Western arms companies. Aiming to control vital fossil fuel stores, Western militaries transfer weapons in an effort to outsource regional control and bolster the military capacity of recipient states. Arms trade to allies such as Egypt or Saudi Arabia continues to be huge, accounting for 35 percent of total global arms imports between 2015 and 2019. This trade, however, is not in line with the UN Arms Trade Treaty and the EU Common Position on military exports. These countries, as regional powers who control both fossil fuel sources and sea lines of transport, fulfill a crucial military role that overrides any peace or human rights scruples arms exporting governments might have.

Although militaries are well aware of climate change and have to deal with its consequences, NATO prioritizes its deterrence and defense posture over emission reduction. Military infrastructure is made more energy independent, but experiments with sustainable propulsion fuel, one of the largest sources of military emissions, are met with technical, financial, and environmental constraints. The most realistic way to reduce military emissions is to reduce the military itself. In a world where the biggest threats come from global problems, such as pandemics and climate change, international cooperation will provide more security than military competition.

The Inextricable Link Between the Arms Trade and Fossil Fuels

The international arms trade and oil are inextricably linked. The clearest examples of this are literal arms-for-oil deals. The most well-known is the Al Yamamah series of arms deals between the UK and Saudi Arabia—Britain’s largest arms deal ever. The deals, the first of which was concluded in 1985 and the most recent of which encompasses the 2008 sale of Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jets, has earned prime contractor BAE Systems tens of billions of pounds. Saudi Arabia paid the UK by delivering up to 600,000 barrels of crude oil per day. The deals have been surrounded by allegations of corruption; an investigation by the British Serious Fraud Office was aborted in 2006 under pressure from the Saudi and British governments.

More generally, fossil fuels have been a major driver of many recent wars and military interventions. Fuel is essential for the mass consumption-based economies of Western countries. As formulated in the NATO Strategic Concept: “All countries are increasingly reliant on the vital communication, transport, and transit routes on which international trade, energy security, and prosperity depend.” Not only are fossil fuels essential for economies, they are also a precondition for military action; they are as essential as bombs and ammunition. There is no military superiority without energy, and fossil fuels are the primary source. Uninterrupted access to energy—energy security—is a precondition to winning a war. “Energy security should be a constant item to be monitored, assessed, and consulted among Allies,” writes the high-level NATO Reflection Group in a 2020 paper preparing a new NATO strategy.

While military infrastructure is well on its way to becoming more energy independent, it is much harder to update military transport and mobility fuel sources, which is where most climate pollution takes place. A shift to sustainable propulsion fuel is not expected soon, and the military will therefore continue to be a huge fossil fuel consumer. For that reason, control of fuel-rich areas and sea lines essential for supply will stay on top of the military’s priority list, to not only secure one’s own access to fossil fuels but also to have the ability to deny access to major competitors, notably China.

If nothing changes, control of fuel resources and supply lines will remain a top priority for Western militaries for years to come due to fossil fuel lock-in caused by ever-increasing military investment coupled with the long life-cycles of existing military technology. This is a driving force for military power projection outside Western territory. In particular, the Middle East is paying a high price for the struggle for control over fossil fuel. For example, the official reason for the 2003 military invasion of Iraq by the United States and allies was the claim, later proven false, by U.S. intelligence services that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. While the arms industry and private military companies profited considerably, the Iraqis paid a high price. At least 185,930 civilians have lost their lives in the violence since the overthrow of the Saddam Hussein regime. Then, in 2004, former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney was honest about the cause of war: “Oil is unique because it is so strategic. We are not talking about soap powder or fashion here. Energy is really fundamental to the global economy. The Gulf War was a reflection of that reality.” In short, the war in Iraq was waged to guarantee the free flow of oil.

Allies in the Middle East play a central role in securing Western fuel supplies. Arms exports are used as an instrument of foreign policy and by transferring weapons, either for profit or as a gift, countries seek to improve the military capacity of recipient states. By a kind of “outsourcing” of regional control, allies are provided with military equipment, including weapons, and training. The aim to control fossil fuels leads to extensive and uninterrupted arms transfers to strategically located countries, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. Arms imports into the Middle East increased by 61 percent between 2010 and 2019 and accounted for 35 percent of total global arms imports between 2015 and 2019. The majority of these arms are provided by the United States and European nations, who are also major buyers of Middle Eastern fossil fuels. Thus, arms-exporting countries experience an additional advantage when fossil fuel revenues earned in the Middle East are “recycled” into their economies. In addition, the amount of arms imported has a direct correlation with the amount of oil exported to the arms supplier. Oil-dependent countries tend to export more arms to oil-rich states, on the premise that it will help guarantee stability in these countries and prevent price increases.

Many of the top clients for the EU arms industry are authoritarian regimes and/or are guilty of internal human rights violations. Treaties and policies to control arms trade, such as the UN Arms Trade Treaty and the EU Common Position on arms exports, include criteria that should prevent weapons from arriving in countries where rights are violated or which are involved in war. However, these criteria are formulated in deliberately vague terms, specifically to leave space for military and strategic interests to overrule peace and human rights. A reviewof EU arms exports in 2018 alone shows exports to eleven countries involved in armed conflicts, including in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Israel, and Turkey. The EU’s intention to “set high common standards which shall be regarded as the minimum for the management of, and restraint in, transfers of military technology and equipment by all Member States (…and) to prevent the export of military technology and equipment which might be used for internal repression or international aggression or contribute to regional instability” does not seem to work in all situations. Economic and military interests override peace and human rights considerations.

The same is true for U.S. arms exports. Although U.S. President Joe Biden is preparing an overhaul of arms export policy to increase the emphasis on human rights, he made his priorities very clear when his government announced major arms sales to the Al-Sisi regime in Egypt in February. A government press release argued that the sale would “support the foreign policy and national security of the United States by helping to improve the security of a Major Non-NATO Ally country that continues to be an important strategic partner in the Middle East… The proposed sale will support the Egyptian Navy’s Fast Missile Craft ships and provide significantly enhanced area defense capabilities over Egypt’s coastal areas and approaches to the Suez Canal.”

Oil a Priority, Despite Conflict

In a world facing a climate disaster one would expect defense organizations to become less focused on fossil fuels. This is not the case. Militaries are adapting to climate change by integrating climate risks into security assessments, not by reducing fossil fuel consumption and emissions. It’s not that they are not aware of the severe consequences climate change might have. Troop readiness might become hampered by heatwaves; weapon systems might suffer from extreme temperatures; installations, notably naval bases, are vulnerable to impacts such as melting ice, crumbling coastlines, and extreme weather conditions. In 2019, the U.S. Congressional Research Service identified more than 1,700 global military installations on coastlines that could prove vulnerable to rises in sea levels. Additionally, a 2019 survey of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) involving 79 installations warned that about two-thirds are vulnerable to recurrent flooding and another one-half are under threat by drought or wildfires. Armed forces are busy adapting their infrastructure, gear, and weapons to extreme weather conditions instead of investing in renewable alternatives.

The consequences of climate change will increase the risk of conflict. Diminishing resources, scarcity, drought, floods, and extreme weather fuel tensions and will add to other inflammatory factors, making violence more likely. Until now climate change has not been a primary contributor to armed conflict, but experts predict it will become a major driver if countries fail to reduce emissions and climate change continues.

NATO consents that climate change will make it harder for militaries to carry out their tasks and has potentially disastrous consequences. The NATO Climate Change and Security Action Plan states: “The implications of climate change include drought, soil erosion and marine environmental degradation. These can lead to famine, floods, loss of land and livelihood, and have a disproportionate impact on women and girls as well as on poor, vulnerable or marginalized populations, as well as potentially exacerbate state fragility, fuel conflicts, and lead to displacement, migration, and human mobility, creating conditions that can be exploited by state and non-state actors that threaten or challenge the Alliance.”

For the victims of climate change—the poor, vulnerable, or marginalized populations that will be forced to migrate—Western countries are preparing a harsh welcome. In response to the increasing number of refugees and migrants, borders are militarized and then legitimized by depicting migrants and refugees as security threats. Yet, for the arms and security industry, this offers business opportunities. The global market for border technology was estimated to be worth approximately €17.5 billion in 2018, with an expected annual growth rate of at least 8 percent in the coming years. Big arms companies, such as Airbus, Thales, Leonardo, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Northrop Grumman, and L3 Technologies, are among the biggest profiteers of this market. The dramatic consequences of the border technology market can be seen in the Mediterranean, where hardly seaworthy boats are intercepted by European and North African navies and coast guards, forcing desperate people to take even more dangerous migration routes.

Estimating and Eliminating Carbon Emissions

Under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, military forces are excluded from greenhouse gas emission reduction targets. This compromise, the result of military influence on the U.S. negotiation team, should have helped garner U.S. support for the protocol. Unfortunately, the United States never ratified the agreement, and the military exemption continued. Now, under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, signatory nations are free to choose whether or not to include military carbon emissions in their reduction targets. This decision is left to individual countries, a policy increasingly criticized by civil society organizations and climate activists. Both Scope 1 emissions, (direct emissions from systems and operations) and Scope 2 emissions (emissions from military infrastructure) do not have reporting or reduction obligations. For a complete calculation of military emissions, indirect emissions from the military supply chain (Scope 3) should be included, although arms production is not singled out from national industry emission figures.

The full extent of military carbon emissions is not known—since there is no reduction requirement under the Paris Agreement there is no obligation to report either—but researchers have deduced figures from other sources. Based on U.S. Department of Defense energy consumption, it is estimated that, from 2001–18, U.S. military forces emitted 1.267 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e), a standard to convert all greenhouse gasses into CO2 equivalents for comparison. The war-related portion of those emissions—including for the major war zones of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and Syria—is estimated to be more than 440 tCO2e. The U.S. military alone creates more planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions through its defense operations than entire industrialized countries such as Sweden and Portugal. For the EU, the carbon footprint of military expenditure of member states in 2019 was approximately 24.8 million tCO2e, with the arms production by military industry responsible for 1.7 to 2.3 million tCO2e. Large European arms companies such as Airbus, Leonardo and Thales are among the largest emitters in this sector.

The real challenge lies in reducing Scope 1 emissions from ships, aircraft, and combat vehicles, which are significantly greater than infrastructure emissions. Just as in the civil sector, propulsion fuel forms a bottleneck in the transition to sustainable operation of the military sector. Replacement of fossil-based propulsion fuel with sustainable alternatives so far has not taken off. Transport and mobility of modern Western armies account for about 70 percent of their energy consumption, the majority of which is consumed in the form of jet and diesel fuel. Although land and sea forces use considerable amounts, the air force is the largest consumer of petroleum jet fuel of all the branches of the armed services.

Reducing emissions by enhancing energy efficiency and introducing sustainable energy in infrastructure is relatively easy and already in progress. Solar panels and bio waste installations increasingly contribute to the energy supply of military installations, improving the endurance of military forces during conflict. Their strategic value is undisputed; fuel supply lines are very vulnerable, especially during deployment. Energy independence for military bases and installations will save human lives. For example, fuel convoys supplying military compounds in Afghanistan encountered notorious attacks along a thousands-of-kilometers-long road through rough Pakistani mountains. For the military industry, it creates a new market of mobile green power products to replace traditional generators. Easily transportable, easy to handle, and quick to set up power systems are already advertised as “combat proven,” meaning their merit has been demonstrated on the battlefield which is the ultimate recommendation for military products. Renewable energy can also be used for modest purposes such as heating or cooling barracks or powering small electric vehicles.

Using sustainable energy sources instead of fossil fuels also has a substantial financial advantage as fossil fuel consumption claims a huge fraction of the military budget. This advantage might dissolve, however, when futuristic plans permeate military budgets. One such ambitious plan involves beaming solar power directly from the sun to military outposts in remote locations. A constellation of satellite-mounted solar panels would collect energy on orbit and transfer it to mobile equipment on Earth. U.S. Air Force engineers are developing serious plans, and the world’s fourth-largest military company, Northrop Grumman, is the primary contractor, receiving a $100 million award to further develop the technology. While making military infrastructure more energy efficient and introducing renewable or sustainable energy for strategic and financial purposes, greenhouse gas emission reduction becomes almost a given by-product.

Slow Technology Development

Aircraft manufacturers, many of whom produce for the civilian as well as for the military market, make an effort to let the world believe they are on the brink of developing low, or even zero, carbon planes. Independent research, however, points out that this is overoptimistic despite options being tested, such as mixing biofuel with fossil-based fuel. Unfortunately, a large-scale use of biofuel can hardly be called sustainable, considering that biomass plantations will inevitably operate at the cost of food production. Producing biofuel crops such as palm oil, corn, sugar cane, or soybeans competes with food production for water and land resources and might increase food costs, especially in developing countries. Additionally, land grabbed and trees deforested to grow profitable biofuel crops forces people from their land and destroys their livelihoods. Furthermore, replacing forests withsingle crop plantations causes a further deterioration of biodiversity. The other biofuel alternative, waste-based biofuel, suffers from a finite quantity of usable waste.

The UK Ministry of Defence predicts it will soon introduce 50 percent Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) for the Royal Air Force including for fuel intensive F-35 and Typhoon fighter jets. In 2020, UK Defence Secretary Wallace said: “The UK is leading the way in sustainability and by refining our aviation fuel standards we are taking simple yet effective steps to reduce the environmental footprint of defence. … As we strive to meet this government’s Net Zero carbon emissions target by 2050, it is right that we step up to spearhead these positive changes across both military and civilian sectors.” But this optimistic promotion of a fossil-free air force smells like green wash— creating a false “green” perception to delude a concerned public—instead of drawing the inevitable, but politically unpopular, conclusion that a green military is unlikely to happen in tandem with Paris Agreement targets. Technology, so far, does not support the minister’s claim.

Considering the long time that weapon development takes from first design to final product, the end of fossil fuel- based military systems is far away. Armed forces are locked-in fossil fuel technology. All new fossil fuel-based weapon systems now developed and commissioned will serve for many years to come, contributing to future military emissions. The NATO Summit 2021 communiqué shows the reality of the military’s approach to low-emission warfare. NATO has agreed “to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from military activities and installations without impairing personnel safety, operational effectiveness, and our deterrence and defence posture. We invite the Secretary General to formulate a realistic, ambitious and concrete target for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by the NATO political and military structures and facilities and assess the feasibility of reaching net zero emissions by 2050.” NATO is asking for a feasibility assessment in which effectiveness, deterrence, and defense come first. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is not the priority.

In the civil sector, aircraft builders such as Airbus boast they will produce a zero-emission hydrogen plane ready for service around 2035. Rolls-Royce promises net zero by 2050. It will most likely take many years—if ever—to develop zero-emission planes for civilian transport, let alone to replace supersonic fighter jets or aircraft carriers. However, the climate is running out of time, and 2050 is too late if we want the planet to stay under a 1.5 degree Celsius temperature increase.

Toward a New Security

Armed forces are serious contributors to climate change, and therefore it is high time to give them emission reduction targets. There are several calls from civil society organizations in support of these targets, such as the Conflict and Environment Observatory which asks governments to use COP26—the 2021 United Nations climate change conference—as a platform for taking action. However, with sustainable fuel alternatives lacking, reducing military emissions might require alternative approaches; for example, it is possible to make greater use of simulated environments to reduce training emissions. Additionally, some emission reduction can be gained from improving the energy efficiency of military vehicles and from a shift towards more fuel-efficient systems such as drones which, by virtue of having no crew aboard, are lighter and emit less than their inhabited equivalents. This, however, only makes sense when fighter jets are replaced by drones, not by adding drones to traditional air fleets, as is now planned with Europe’s Future Combat Air System. Moreover, the use of drones raises many ethical problems that are yet unsolved, including the possibility of lowering the threshold of violence by removing the political costs of deploying manned military operations.

Realistically, the best way to reduce military carbon emissions is to reduce the size of the military itself. In both the military and the civil sector, limiting emissions requires a change from more and bigger to less and smaller. Recent reductions in U.S. military carbon emissions can be expected from the reduction in large-scale overseas operations, such as the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan. On the other hand, rising defense budgets, such as the 2.7 percent increase in NATO members military spending in 2020, will inevitably lead to higher emissions. While larger military budgets are warmly welcomed—and lobbied for—by the arms industry, they are disastrous for the future of our planet, leading us further down the path of growing international tensions, increasing violence, and a worsening climate crisis.

The key to shrinking the military is reducing military tensions. Rather than looking for new, lower-carbon ways to fight wars, governments should be prioritizing measures such as diplomacy, international disarmament treaties, addressing the root causes of conflict such as unfair distribution of wealth, and, of course, reductions in carbon emissions across the economy to prevent further climate destabilization. Idealistic as this may sound, these measures are more realistic than increasing military and economic competition in a world where a global pandemic and climate change are the outstanding threats, both of which can only be solved if countries cooperate. We must change the way in which we strive for security—from competition to cooperation—and we have to do it soon. Because, as protesting youngsters in the streets are desperately screaming at us, we are running out of time.

Wendela de Vries is a long-time researcher and campaigner against arms trade and military industry at the independent peace organization Stop Wapenhandel, of which she is co-founder. She is part of the Steering Group of the European Network Against Arms Trade and coordinates an international working group on arms, militarism, and climate justice.

Read More