Delivering the Palestinians to Israel: The Lasting Effects of the 1973 War on the Palestinian Question

In the years following the creation of Israel, the United States became the game master of the Arab-Israeli peace process. For Palestinians, this meant that they would not have a seat at the table for decades to come

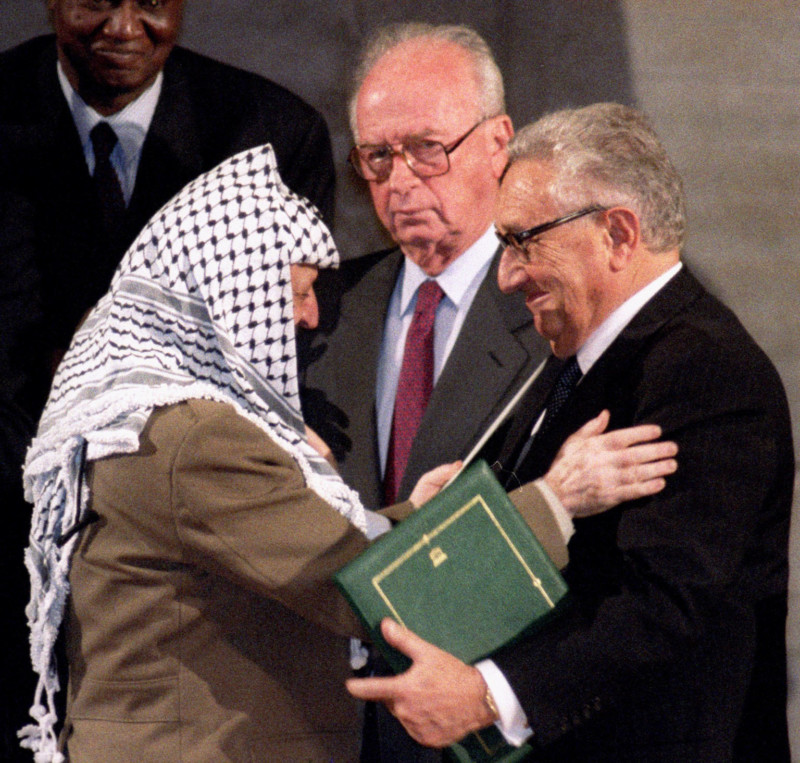

Nobel laureates Yasser Arafat embraces Henry Kissinger after being awarded the Félix Houphouët-Boigny Peace Prize. July 6, 1994. Christine Grunnet/Reuters

While the June Six-Day War in 1967 is widely regarded as the seminal event in Arab-Israeli geopolitics and diplomacy, the effects of the October War of 1973 have been equally, if not more critical, in shaping the post-1967 political and diplomatic order. The period following the 1973 War remains perhaps the most dynamic and formative in shaping Arab-Israeli peacemaking and U.S. and Palestinian official postures toward one another over the next half century. Almost every aspect of the contemporary Middle East peace process and U.S.-Palestinian relations can be traced to the critical months and years immediately following the 1973 War.

It was only after the 1973 War that the United States, with all its political and ideological idiosyncrasies, emerged as the undisputed leader of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Moreover, the policies and priorities put in place by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger—seen as both the architect of the Middle East peace process and the godfather of U.S.-Palestinian policy—would go on to shape Arab-Israeli peacemaking for most of the next half century. These included the preference for a piecemeal peace process over comprehensive settlement negotiations, reliance on American and Israeli preeminence, and, most importantly, the strategic downgrading of the Palestinian issue. The 1973 War also marked a decisive shift in the diplomatic strategy of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In the wake of the war, PLO leaders came to the stark conclusion that the road to Palestinian statehood ran exclusively through Washington, even as U.S. officials sought to exclude Palestinians from the diplomatic process in the decades that followed.

These same basic dynamics persisted even after the PLO joined the peace process in 1993, whereby the Palestinians were granted a conditional seat at the table in the hope of transforming the Palestinians into a suitable peace partner. Palestinian leaders were prepared to cede a measure of their internal autonomy with the expectation that the United States would eventually deliver Israeli concessions. In the end, the process succeeded only in institutionalizing Palestinian dependency and weakness.

The Conflict Begins (1948–1973)

Israel’s creation in 1948 entailed the destruction of Arab Palestine and the displacement of roughly two-thirds of its Arab population, an event known as the nakba, or “calamity”. Afterwards a new generation of Palestinian political leaders and institutions took up the mantle of Palestinian liberation. New paramilitary units, known as fedayeen, took up arms against the nascent state of Israel with the aid and encouragement of various Arab regimes. The 1950s and 60s also saw the emergence of new semi-autonomous Palestinian political forces, such as Fateh in 1959 and the Arab National Movement (ANM)—the precursor of the leftist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP)—as well as the Arab League-sponsored Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1964. The United States and other western powers, while nominally supporting a diplomatic resolution based on United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, which affirmed the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, continued to view the Palestinian question as a distinctly humanitarian and increasingly pressing security issue, rather than a political one.

It was only after the 1967 war that U.S. officials began to look at the Palestinians as political actors in their own right. Israel’s occupation of the remnants of Arab Palestine, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), and Gaza Strip, foisted the Palestinian issue back into the global spotlight. Even so, UN Security Council Resolution 242, which called on Israel to withdraw from Arab territories occupied during the war in return for peace with Arab states—the so-called “land for peace” formula—failed to mention the Palestinians as being anything other than refugees. Meanwhile, the humiliating defeat of combined Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordan forces convinced the Palestinian factions and fedayeen groups on the need to take matters into their own hands. By early 1969, the fedayeen had taken control of the PLO and, under the leadership of Fateh’s Yasser Arafat, transformed the organization into a genuinely autonomous, and broadly representative Palestinian, decision-making body.

In the years after 1967, particularly following the PLO-Jordan civil war of late 1970, Palestinian nationalism had emerged as a potent political force in the region. Moreover, despite its defeat and subsequent expulsion from Jordan, the PLO was now the central address for the Palestinian national movement. With its commitment to armed struggle and positioning Palestinian liberation within the global context of anti-imperialism and decolonization, the PLO built alliances with other liberation and revolutionary movements across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, while remaining largely ambivalent toward the superpower rivalry. Although the PLO was formally part of the nonaligned movement, sentiment within the organization leaned heavily toward the Soviet Union while remaining deeply distrustful of the United States because of its role in Israel’s creation.

American officials, for their part, remained highly conflicted in their approach to the Palestinians. While a growing number of U.S. officials in the foreign service and intelligence communities recognized the need to accommodate Palestinian political aspirations in some form, most U.S. officials remained highly distrustful of the PLO, in no small part due to intense Israeli opposition to any accommodation with the PLO or Palestinian nationalism. The PLO’s involvement in violence, including terror attacks on U.S. and other western targets, also soured U.S. officials on the organization.

Despite their mutual suspicions (and perhaps because of them), starting in 1970 the PLO leadership and U.S. security officials agreed to establish a mutually beneficial secret backchannel run through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). While the PLO leadership hoped the clandestine talks would ultimately lead to a political dialogue with Washington, U.S. officials viewed it in strictly utilitarian terms. The PLO-CIA track proved invaluable in the intelligence and security realms, providing valuable intelligence on a wide range of anti-American threats, including thwarting terror plots by rogue Palestinian factions, but would remain decidedly apolitical.

Few U.S. officials were more hostile to Palestinians than Henry Kissinger, the chief architect of Nixon’s foreign policy who served as national security advisor before becoming secretary of state in the weeks before the 1973 War. For Kissinger, a staunch Cold Warrior, the PLO was little more than a group of radicals and a tool of the Soviet Union as well as a political nonstarter for Israel. Thus, not only would the PLO have no role in any future peace process but would need to be marginalized and weakened for Arab-Israeli diplomacy to succeed. Despite intense antipathy toward the PLO, however, Kissinger was not opposed to engaging with it, both for its utility in the intelligence sphere and as a way to limit its troublemaking ability.

Shifting Perceptions: The 1973 War and its Aftermath

The October War reshuffled the geopolitical deck once again, as well as U.S. and PLO postures toward one another. The war shattered the aura of Israeli invincibility, giving rise to a new diplomatic process centered around an international peace conference to be held in Geneva before the close of the year with the aim of pursuing a comprehensive peace between Arab states and Israel. Although officially sponsored by both superpowers, the Geneva conference and the peace process itself was now the sole purview of the United States in general and of Kissinger in particular. The war also marked a strategic, decisive shift in the PLO’s approach to Palestinian liberation, which now began to downplay armed struggle in favor of diplomacy. Moreover, like Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Arafat had concluded that the United States held all “the cards” and that the road to a future Palestinian state ran inexorably through Washington. While the Soviet position was considerably more in line with the PLO’s sentiments and aspirations, only the United States, it was believed, could deliver Israel—a belief that would shape PLO diplomacy for the next half century and is still evident today.

Hoping to earn the PLO a seat at the table in the Geneva process, Arafat intensified his outreach to Washington in the months following the war. This time American officials were more responsive, with Kissinger authorizing CIA Deputy Director Vernon Walters to meet with Arafat’s confidantes in Morocco in the months before and after Geneva. Tapping both the CIA track and various third parties, Arafat conveyed a series of increasingly bold messages to the Nixon administration, including explicit recognition of Israel and willingness to live in peace with it. The PLO “in no way seeks the destruction of Israel, but accepts its existence as a sovereign state,” Arafat privately assured the Americans in December 1973, while noting that the PLO’s primary political aim was “the creation of a Palestinian state out of the ‘Palestinian part of Jordan’ [i.e., the West Bank] plus Gaza.” This was the first, albeit unofficial, endorsement by the PLO leadership of a peace settlement based on a two-state solution, fifteen years before it became official PLO policy and a quarter century before either the Israelis or the Americans came around to the idea. It was also a highly risky move from the standpoint of domestic Palestinian politics, where such ideas remained highly contentious, if not treasonous.

Despite Arafat’s apparent willingness to engage with his adversaries, Kissinger had no intention of bringing the PLO or the Palestinians into the negotiations, which he felt would only “radicalize” the Arab states and enrage the Israelis. Thus, while Arafat hoped to use the dialogue to demonstrate the PLO’s moderation and pave the way for its entry into the peace process, Kissinger viewed it solely as a way to gain some diplomatic “maneuvering room” while limiting the PLO’s ability to create problems for his diplomatic strategy—the central focus of which was not the Geneva conference.

Kissinger had little interest in a multilateral process that would afford the Soviets an equal role to the United States or that would allow Moscow to serve as the “lawyer” for the Arab side at the United States’ and Israel’s expense. The Geneva process was therefore primarily for international, and especially Arab and Soviet, consumption. The real process, meanwhile, would be conducted by Kissinger through “step-by-step diplomacy.” Under this formula, the Egyptian, Jordanian, and Syrian tracks would be handled separately, thus preventing the emergence of a unified stance toward Israel and ensuring both American and Israeli preeminence. In the first phase, Kissinger focused on brokering disengagement agreements between Israel, Egypt, and Syria, with the ultimate aim of securing separate peace deals between Israel and each of its Arab neighbors. Egypt, as the most potent political and military threat to Israel, was especially crucial to Kissinger’s plan, especially since Sadat had signaled his intention to turn away from the Soviet Union in July 1972. The Palestinians would be brought in at the end of the process, preferably after the PLO had been weakened. The “Palestinian problem,” in any event, was not a matter that concerned Israel but rather “an inter-Arab concern” whose resolution lay with Jordan’s King Hussein rather than the PLO.

Despite being cut out of the Geneva process, Arafat continued to push a pragmatic agenda, both internally and externally, while working to enhance the Palestinians’ international standing. In June 1974, Arafat’s convinced the PLO’s parliament-in-exile, the Palestine National Council, to adopt a new political program which called for the establishment of a “fighting national authority” on any liberated part of Palestinian territory. Although rejected by hardline PLO factions like the PFLP and the Syrian-backed Al-Saiqa, the measure was widely regarded as a win for PLO moderates.

The PLO’s stepped-up diplomacy underscored a broader shift in international and U.S. attitudes toward the Palestinian issue in the aftermath of the October War, especially among large segments of the U.S. national security and intelligence establishments. By early 1974, the Soviet Union had effectively normalized ties with the PLO, while the Europeans for the first time publicly acknowledged the Palestinians as a party to the conflict as well as their “legitimate rights”. Moreover, by early 1975, key elements within both the State Department and the White House had come out in favor of engaging with the PLO, which despite some if its more distasteful activities, was a political reality that enjoyed the sympathy and support of millions of Palestinians. Even Congress, where pro-Israel and anti-PLO sentiment ran especially high, was beginning to show signs of change, as a number of senators and representatives spoke openly for the first time about Palestinian rights and past suffering.

Yet, Kissinger remained unmoved and viewed the PLO’s growing international acceptability with growing frustration and alarm. After the Arab League’s October 1974 vote to recognize the PLO as “the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people,” Kissinger blasted the decision as a “fit of emotional myopia” that undercut King Hussein’s claims over the West Bank while empowering the one actor [the PLO] Israel was unwilling to negotiate with. A month later, the UN General Assembly—despite strong U.S. objection—followed suit and voted to recognize the PLO as the official “representative of the Palestinian people” while affirming the “right of the Palestinian people to self-determination”. To add insult to injury, Arafat was invited to address the world body. “Today I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom-fighter’s gun,” declared Arafat in his now famous address before the UN General Assembly, “Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.”

Despite Washington’s intense hostility toward the Palestinian leader, U.S. officials continued to engage with the PLO. As if to underscore U.S. ambivalence, on the day of Arafat’s speech, senior PLO and CIA officials met in an upscale Manhattan hotel to hammer out an agreement on security- and intelligence-sharing and on the training of Palestinian forces that would provide security for U.S. diplomats in Beirut. But if Arafat thought that collaborating with the CIA would make it impossible for Washington to continue ignoring the PLO politically, then he was in for a rude awakening.

Following the UN vote, developments on the American-Palestinian front evolved rapidly—but in two different directions. As Washington became more open to Palestinian perspectives and aspirations, the door to Palestinian participation in the political process was simultaneously being closed. Within weeks of the UN vote, even as PLO forces began providing security escorts for U.S. diplomatic personnel in Beirut, the Ford administration issued a blanket ban on visas to PLO members, exempting only the PLO’s UN personnel. American official ambivalence was on full display in late 1975.

The shift in attitude was particularly pronounced on Capitol Hill, where in the fall of 1975 the House of Representatives held a series of groundbreaking Congressional hearings covering all aspects of the Palestinian issue, including, for the first time in decades, testimonies from prominent Palestinian voices. While a handful of Congress members spoke about Palestinian rights, a few of their more daring colleagues set off to meet with Arafat at his headquarters in Beirut.

The Ford administration was also showing signs of change, using the fall 1975 Congressional hearings as a platform to announce a new approach to the Palestinians. Administration officials reiterated the standard U.S. position that any future peace process should take into account “the legitimate aspirations or interests of the Palestinians,” and for the first time also recognized the Palestinian question as a political matter and not merely a humanitarian one.

Washington’s apparent openness to the Palestinian question did not translate into a more accommodating policy toward the PLO or the Palestinians, however. In fact, the opposite occurred. Even before the Congressional hearings on the Palestinians had commenced, in an attempt to push stalled Egyptian-Israeli disengagement talks, Kissinger signed a secret memorandum of agreement (MOA) with the Israelis, pledging that the United States would not “recognize or negotiate with” the PLO until it recognized Israel’s right to exist and accepted Security Council Resolution 242. Arafat, owing to his own domestic opposition, was in no position to publicly accept such conditions, as Kissinger and the Israelis no doubt understood, particularly in the absence of any comparable concessions by Israel.

Lasting Legacies: From Camp David to Oslo and Beyond

Kissinger’s MOA would effectively tie the hands of subsequent U.S. administrations in their ability to effectively mediate between Israelis and Palestinians. More to the point, the peace process designed by Kissinger in the aftermath of the 1973 War—with its focus on American and Israeli preeminence, piecemeal progress, and a strategic aversion to the PLO—would become a template for all future American peacemaking in the Arab-Israeli arena in both procedural and ideological terms. In addition to solidifying U.S. “ownership” over the Arab-Israeli negotiations, Kissinger’s policies succeeded in keeping the PLO out of the peace process for nearly two decades, as well as in prioritizing separate peace deals between Israel and each of its Arab neighbors over a comprehensive peace settlement, all of which were designed to prioritize U.S. and Israeli interests over those of the Arab states and their backers. Even the Carter administration, despite its preference for a comprehensive peace and persistent attempts to bring the PLO into the peace process, ultimately reverted to the Kissinger model, thanks both to the 1975 MOA and Egypt’s decision to pursue a separate peace with Israel in 1978.

The proposal for limited Palestinian autonomy contained in the 1979 Camp David Accords became a precedent for dealing with the Palestinian track, not just as a model for a future interim arrangement (i.e., the Palestinian interim self-governing authority stipulated in the 1993 Oslo Accord) but also for its willingness to determine the fate of Palestinians without their participation.

Moreover, the exclusion of the PLO was not strictly a function of the group’s actions but also reflected a particular ideological view that fundamentally devalued—even pathologized—the politics and aspirations of the Palestinians. While Kissinger’s disdain for the Palestinians was by no means unique—and may well have been an inevitable byproduct of the “special relationship” and the Israel-centric lens through which U.S. policymakers and politicians viewed the issue—he nevertheless succeeded in elevating this mindset into an article of faith of the U.S.-led Middle East peace process, of which the formal exclusion of the PLO was only one part.

This same constancy is evident on the other side of the equation. Since the mid-1970s, the PLO leadership, with very few exceptions, has remained remarkably loyal to a U.S.-led peace process—even when it was clear that the United States could not deliver. Israel’s disastrous invasion of Lebanon in 1982, in which a U.S.-brokered ceasefire failed to prevent the massacre of some one to three thousand Palestinian refugees at the hands of pro-Israel Lebanese militiamen, marked one of the bloodiest episodes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as well as the first instance of U.S. mediation between the PLO and Israel. The Lebanon debacle left the PLO badly weakened and internally divided but otherwise did nothing to diminish the PLO’s faith in Washington, which only intensified in the decades that followed.

The PLO eventually joined the peace process in 1993, although from a position of weakness, as Kissinger had hoped. Indeed, the Oslo process itself, as a set of interim deals with a focus on incremental progress and lacking a clear endgame and in which the United States served as the sole mediator, was quintessentially Kissingerian.

Moreover, if the PLO leadership had spent most of the 1970s and 80s trying to join a U.S.-led peace process, the advent of the Oslo process effectively cemented the PLO’s American strategy. The fact that Oslo was not simply a process of conflict resolution between two parties but also a process of “state-building” for the Palestinians gave outside actors, including the United States, foreign donors, and even Israel, a direct say in—and in many ways an effective veto over—key aspects of Palestinian political life. Under U.S. stewardship, the Oslo process became as much a tool for transforming Palestinian politics as for Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking. If the Palestinians’ entry into the peace process was predicated on the PLO being tamed, as Kissinger had sought, then the Oslo process would help ensure that its successor, the Palestinian Authority (PA), would be fully domesticated.

The Palestinian leadership, for its part, was willing to give up a degree of control over internal Palestinian politics and decision-making in the hope that the United States would ultimately “deliver” Israel, namely by convincing Israel to end its occupation and enable the creation of a Palestinian state. Oslo did not lead to Palestinian independence, however, but instead deepened Palestinian dependence on the United States and on Israel. Moreover, as the two most powerful actors bound by a special relationship, the United States and Israel had both the ability and the incentive to shift as many of the political risks and costs onto the Palestinians as possible, especially when things went wrong. This was the case following the collapse of the Camp David summit and the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada in 2000, as well as the repeated violent eruptions in Gaza and other subsequent crises.

Despite occasional attempts by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to break free from, or at least moderate the PLO’s longstanding “American strategy,” the Palestinian leadership remains too weak and dependent on the United States, as well as Israel, to abandon the strategy completely. In the end, initiatives such as attempts to join international bodies, seek redress from the International Criminal Court, pursue reconciliation with Hamas, or sever security ties with the United States and Israel have almost always been either tactical in nature, short-lived, or both. Moreover, the Palestinian leadership’s inordinate dependence on the United States has come at an increasingly high price domestically. Not only has the single-minded focus on American deliverance over the previous five decades failed to bring Palestinians closer to independence, it has actually helped weaken Palestinian politics, institutions, and leaders, limiting the Palestinian leadership’s freedom of action while simultaneously eroding its domestic legitimacy.

When Success Breeds Failure

Looking back at the last half century of Arab-Israeli peacemaking and American-Palestinian relations, it is hard to escape a basic paradox. On the surface, both the U.S.-led peace process and the PLO’s “America strategy” were highly successful, as both largely achieved what they initially set out to accomplish. The diplomatic process that Kissinger engineered, with considerable help from Congress and the pro-Israel lobby, effectively kept the PLO and the Palestinians out of the peace process for the better part of two decades, while domesticating Palestinian political and governing institutions thereafter. Likewise, the PLO succeeded in eventually joining the U.S.-led peace process and in enlisting American support for Palestinian statehood.

And yet, both of these seem like pyrrhic victories today. Indeed, the process Kissinger created worked too well, first by delaying the PLO’s entry into the peace process and then by attempting to tame it. In the end, the Oslo process institutionalized Palestinian weakness and dependence on the United States and Israel, in ways Kissinger could only have dreamt. At the same time, a weak and divided Palestinian leadership, far from being an asset to the peace process as Kissinger had expected, has instead become a source of chronic violence and instability. For most of the last fifty years, the Palestinian leadership, from Arafat to Abbas, has wagered on the United States as the only party capable of compelling Israel to end its occupation and of allowing the emergence of an independent Palestinian state. The lopsided power dynamics that Kissinger was so keen to enshrine in the peace process, however, reversed that formula. Instead of the United States delivering Israel, the U.S.-led peace process ended up delivering the Palestinians to Israel. Instead of Palestinian statehood or independence, the peace process eroded Palestinian agency, as well leadership’s domestic legitimacy and internal Palestinian political cohesion.

Khaled Elgindy is senior fellow and director of the Program on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli Affairs at MEI. He is the author of the new book, Blind Spot: America and the Palestinians, from Balfour to Trump (Brookings Institution Press, April 2019). Elgindy previously served as a fellow in the Foreign Policy program at the Brookings Institution from 2010 through 2018. Prior to arriving at Brookings, he served as an adviser to the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah on permanent status negotiations with Israel from 2004 to 2009, and was a key participant in the Annapolis negotiations of 2007-08. Elgindy is also an adjunct instructor in Arab Studies at Georgetown University.

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter