A Revived Arab Peace Initiative from Saudi Arabia Could Save the Middle East

Understanding Saudi pragmatism toward Israel, and its historical balancing act, is crucial for reviving the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative and countering the Abraham Accords’ erasure of Palestinian rights

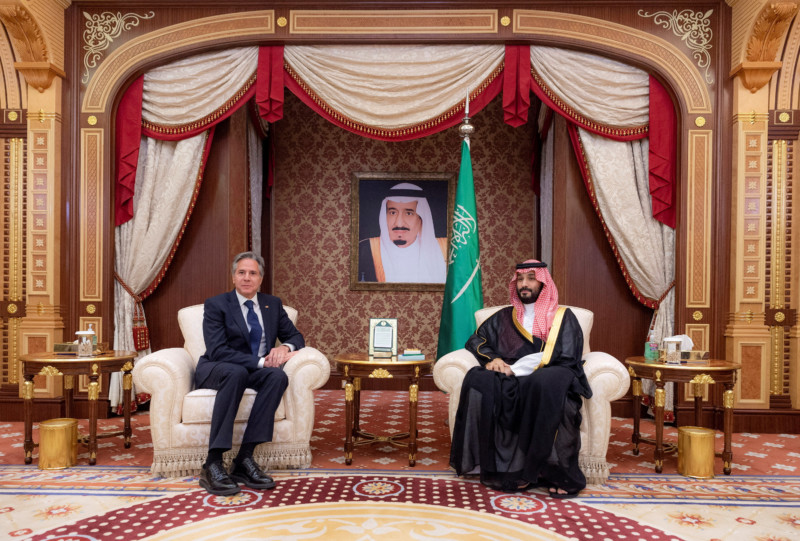

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken meets with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Nin Salman, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, June 7, 2023. Bandar Algaloud/Courtesy of Saudi Royal Court/Handout via Reuters

In 2002, during their annual summit in Beirut, the twenty-two members of the Arab League proposed the Arab Peace Initiative (API), which called for normalizing relations with Israel on the condition of the establishment of a viable Palestinian state.

The API was initially meant to be a framework to peacefully end the decades-old conflict. While that framework still remains intact today, the API has played a different function since the Arab Spring jolted the region into an intense zero-sum game between Saudi Arabia and Iran. From then on, Saudi official discourse treated the API as a focal point in the Kingdom’s pragmatic policy toward Israel. It gained a simultaneous function that allowed the Saudis to express their willingness for cooperation, yet still distance themselves from such willingness by emphasizing the centrality of Palestinian rights.

In the years since the 2002 summit, the API would not only become the last vestige of the land-for-peace formula as a solution to Israel’s occupation of Palestine, but also came to be seen by its progenitor, Saudi Arabia, as the most enduring basis for a lasting peace in the Middle East.

With successive peace efforts failing and falling to the wayside, the API was eventually overshadowed when several Middle East states signed normalization agreements with Israel in 2020 and 2021 within the framework of the Abraham Accords—without guarantees for Palestinian rights. Nevertheless, in the past year, and prior to the current Israeli war on Gaza, Saudi Arabia was considered by both Tel Aviv and Washington to be the biggest regional player expected to normalize relations with Israel.

For this reason, the Kingdom’s pragmatic policy toward Israel is often misunderstood by a wide range of regional and global observers and actors, to the detriment of the API. Therefore, it is important to properly frame Saudi engagement with Israel within Saudi Arabia’s history of strategic balancing, and to focus on recontextualizing the API in the post-October 7 world rather than looking to the Abraham Accords as a pathway to peace.

History of Strategic Balancing: “Not Too Close But Not Too Far”

The Saudi position toward Israel can generally be depicted as operating in a constant state of balance; the Saudi ruling elite have historically had to weigh normative Arab and Islamic obligations that are crucial to their image and legitimacy on one hand, with a great deal of diplomatic and security interests with their traditional Western partners on the other.

This weighted approach by the Saudi monarchy to Israel is all the more complex when one considers that it is based on a trilateral relationship with the United States, perhaps the Kingdom’s most influential strategic partner.

This balancing act requires delicate strategic measurement and a discursive process that may lead analysts and policymakers worldwide to adopt false working assumptions that the Saudis will largely abandon Palestinian rights in any future peace process. Therefore, it would be fruitful to provide a historical perspective of how far back Saudi pragmatism toward Israel stretches to get a clearer idea of its future.

One of the enduring misconceptions on this topic is the idea that Saudi willingness to normalize ties with Israel is something new when it actually dates back to the late 1960s. When an American consular delegation met King Faisal in Dharan in 1969, American officials were surprised by the tone of the late king regarding Israel. The King even then was already blessing negotiations with Israel, but not direct Saudi–Israeli talks. This attitude was mainly due to the prevalent opinion among most Arab leaders after the 1967 Arab defeat that Israel was a de facto reality on the ground, and therefore there would be no recourse but to engage and pursue a settlement with it.

Even in the years after the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, Saudi officials were still not opposed to negotiations with Israel. In fact, their intention to lead the oil embargo was a means to apply pressure on the Richard Nixon administration to start a negotiated process to resolve the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Even when Egyptian President Anwar Sadat surprised the Arab World with his trip to Jerusalem, the Saudi ruling elite, notwithstanding their bitterness for not being informed beforehand, were supportive of negotiations with Israel. Of course, these instances were discussed quietly and discreetly, and such a position could not have been made public at the time due to popular sentiment. However, this illustrates that the balancing and measured position of Saudi Arabia toward negotiations with Israel is something that has been present for decades and ought not be considered new.

It was not until 1981 with Saudi Crown Prince Fahd Abdul Aziz’s peace plan, which materialized into the Fez plan of 1982, that the position of Saudi pragmatism toward Israel became more public. The Fez Plan called for an independent Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital and for the “dismantling of the settlements established by Israel in the Arab territories since 1967”. The response of then-Prince Abdullah, when asked whether or not the Fez plan offered recognition of Israel, was to the effect of “how could it not”. This demonstrates that even public Saudi pragmatism and willingness to recognize Israel is really nothing new. On the other hand, the eruption of the Iran–Iraq War (1980-1988) and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait (1990) forced Saudi Arabia to focus on its imminent security issues rather than on peace in Palestine and Israel.

Operation Desert Shield/Storm during the 1991 liberation of Kuwait was a milestone in Saudi–Israeli relations. It essentially forced both states to be at the receiving end of Iraqi missiles amid Saddam Hussein’s miscalculated madness. Israel’s passivity in the war and its lack of complication of the Arab coalition amassing on Saudi territory to dislodge Iraq from Kuwait helped thaw the negative perception that the Saudi ruling elite had of Israel. However, they were still reluctant to imply any sort of tacit recognition of Israel—something they wanted to avoid—through their attendance of the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference. The Saudi ruling elite were already wary of public sentiment and society’s response to the large American presence on Saudi soil—they had to be careful.

Notwithstanding, the ruling elite did what they do best and balanced their position during the Madrid conference, attending the proceedings but only as the representative of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), and not the Kingdom on its own. This balancing process demonstrated the lead-from-the-back style of leadership the Saudi ruling elite tend to prefer.

In a discussion with U.S. diplomat Dennis Ross, the Saudi ambassador to the United States said that by representing the GCC, it would look as if Saudi Arabia itself is there due its dominant role in the Council. This strategic balancing exemplifies the policy of “not too close but not too far”. Saudi officials communicated their tacit willingness to be present, but also provided themselves deniability of their role in direct negotiations.

The 1990s illustrated the ebb and flow of Saudi policy toward Israel. After the Oslo Accords and the Jordanian–Israeli peace treaty the year after, Saudi policy thawed even further. In 1994, the ruling elite agreed to remove secondary and tertiary measures on the economic boycott of Israel, allowing interaction with companies that do business with Israel. In addition, against the backdrop of efforts toward an American brokered Syrian-Israeli peace, the Saudi ruling elite were willing to normalize relations with Israel as an incentive. However, the breaking down of the Syrian-Israeli peace track and the ushering in of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was not favorable to the Palestinian–Israeli peace process, made the Saudis distance themselves even further.

What contributed to this distance was the eruption of the Second Intifada. After some hope of peace in the Camp David summit in 2000, relations took a turn for the worse. In fact, it was one of the lowest points in Saudi–U.S. relations as then-crown Prince Abdullah sent a measured, yet firm message to the newly sworn in U.S. President George Bush Jr. that Saudi Arabia will have to take its business elsewhere, in light of the president’s overt support of Israeli actions during the Intifada. This public spat between the traditional partners and willingness to strategically shift away from the United States by then-crown prince Abdullah is yet another reminder of the trilateral dynamic of Saudi–Israeli relations. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attack only compounded tensions further. With all the turbulence ensuing from the Intifada, and against the backdrop of the early days of the War on Terror, the crown prince put forth the Saudi peace plan in February 2002. This, in turn, was adopted (with amendments) as the Arab Peace Initiative in March 2002.

After the Arab Spring, the API gained a new function of being a Saudi mechanism to harmonize relations with Israel in the context of the turbulent post-Arab Spring Saudi-Iranian regional rivalry. It performed this function by allowing the Saudis to express their willingness to move closer to Israel and in opposition to Iran, yet maintain a publicly acceptable distance by conditioning peace upon the creation of a viable Palestinian state.

The overture is akin to extending their hand yet pulling themselves back, so as to keep the gesture of normalization there, while deliberately being elusive. The API has therefore been caught in this overarching process of Saudi balancing. Accordingly, it may now require re-articulation in order to become the framework of peace it was supposed to be and evolve beyond merely serving as a focal point of Saudi pragmatism.

How to Revitalize the API

In legal literature, the term living constitution is used to explain how the nature and spirit of laws are relevant for the time in which they are introduced; peace initiatives may be considered in the same manner.

The API, viewed as a living peace initiative, allows itself to absorb the political and geopolitical changes that have dominated the Middle Eastern landscape. What makes the API the go-to framework for peace in 2024 is that it has been imbued and designed broadly and with flexible language that was seen to help negotiations address the core issue: the Palestinian-Israeli conflict—a key component missing in the Abraham Accords. However, the inherent strength of flexibility that facilitates negotiations with Israel is also a soft underbelly, as detractors will use this flexibility to discredit the essence of the API.

Therefore, if the API is to be readopted in the new era, the flexibility within it needs to be used to bring it back into the mainstream through shifting to more explicit language and increasing economic and non-economic incentives for peace. For example, a new API could define the framework of negotiations more explicitly and highlight specific projects that could be collaborated on once progress in talks is made. Moreover, it could highlight a roadmap to peace that clearly indicates milestones and a timetable within this process. Most rulers in the Middle East seem to be entrenched in their seats for the foreseeable future, so they could use time to their advantage rather than operate according to the political calendar of the United States.

Given the growing Saudi ability to position itself in the ever-evolving multipolar world, this is its opportunity to help induce new language. This will entrench the API further into a peace process, and will allow negotiations within the framework of a Palestinian state rather than as a bilateral normalization agreement.

Moreover, the mechanisms of explications should not be confined to governments or official discourse in the region—Middle Eastern civil society, academics, and think tanks can play a more explicit role in this, too. While one is not oblivious to the fact that the regional environment may curtail a certain freedom of expression, the intellectual community in the region needs to play a more public role that can explicate the API.

For example, the intellectual community of regional analysts and academics could elevate the API by conceptualizing notions of sovereignty, security, and peace in a way that complements the spirit of the API and adheres to its paradigm. It may work toward a different understanding of sovereignty that is befitting to the complex situation the Palestinian-Israeli dynamic faces. It could, for example, reimagine and work toward a sovereignty that enables an inclusivity over exclusivity—a sovereignty that is about being broad rather than about being insular. Regarding security, the intellectual community could broaden its conceptual horizon and build a more intertwined, overlapped, and regionalized understanding of security. In a nutshell, what is missing is an intellectual effort that would have political impact and would push the API forward.

Rather than having a purely out-in approach where regional normalization ensues, and then the Palestinian issue gets addressed, the new and improved API could be used as a simultaneous process fusing the Palestinian-Israeli peace with regional reconciliation. In order to bridge the gap between Palestinian-Israeli peace with regional normalization, Saudi Arabia ought to be at the negotiating table to reduce the asymmetry between the Palestinians and Israelis.

Given the evolution of the API and conception of the Abraham Accords, with the latter receiving significant attention, one may question whether it is more prudent to expand upon the more recent initiative given that it is just over three years old. This is a fair question, but the Abraham Accords is beleaguered by a number of conceptual shortcomings which are resolved in the API, making the older paradigm the one worth embracing and expanding.

Look to the API, Not the Abraham Accords, for Regional Peace

One of the aspects that Israel’s War on Gaza has shown is that the region is not ready for more normalization. Instead, there is, more than ever, a dire need for a comprehensive peace in the region.

Leading up to the October 7 war, a great deal of the focus in the halls of the U.S. government was on Saudi-Israeli normalization. The danger of this sensationalist rhetoric of region-wide normalization and abandoning of a Palestinian state is overlooking the simmering and explosive issues on the Palestinian-Israeli front. Focusing on expanding the API, rather than the Abraham Accords, helps recalibrate the bearings toward a sustainable peace, as it is imperative not to conflate nor misunderstand the two different paradigms of peaceful conflict resolution.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to argue that the Abraham Accords have not brought economic benefit to the signatories involved. Economic relations have increased, but this is no surprise, as the economies of the GCC and Israel are complementary due to their tech-based markets. So, in that regard and from a purely bilateral economic perspective, the Abraham Accords are successful—notwithstanding polling suggesting they are unpopular. It is no doubt a milestone in Arab-Israeli relations fashioned in the likes of Jordanian-Israeli and Egyptian-Israeli peace deals.

However, the very DNA of the Abraham Accords is extraordinary, as it is a new paradigm in Arab-Israeli relations. While the API is based on a land-for-peace formula, which means Israel will return occupied Arab land in return for diplomatic recognition, the Abraham Accords is what would be described as a peace-for-peace paradigm: Israel would gain diplomatic recognition from the Arab signatories without any concessions to the Palestinians.

For Israel, as Netanyahu said: the “Abraham Accords enabled us to get out of the equation of land for peace to peace for peace, and we did not give up a span.” This was a strategic gain for Israel not just for more access to the signatories’ markets, but it created an inevitable interaction with Saudi Arabia by flying Israeli commercial airliners over its airspace to the United Arab Emirates, for example. As a result, the Abraham Accords gave confidence to Israeli leaders that they can achieve normalization of ties with the Kingdom without any concessions and without taking Palestinians rights to sovereignty and self-determination seriously.

That is precisely why the API, not the Abraham Accords, needs to be expanded upon and adapted to the new geopolitical context of the post-October 7 Middle East—it simultaneously influences the expectations of a peace process and a peace treaty with Israel so that it has, at its heart, a Palestinian component. The emphasis on the Palestinian cause is exactly what is needed at this juncture, and what the Abraham Accords lack.

At their very foundation, the Abraham Accords are fundamentally not about a Palestinian state, but a circumnavigation of it.

More specifically, the framework of the Accords are dual-layered. The first is an overarching layer of an American foundation that offers the principles of the Abraham Accords—a text that revolves around regional prosperity and ushering in a new era. While that does sound noble, it does not make any reference to a Palestinian state.

The second layer is made of the respective bilateral agreements between Israel, and the signatories of the UAE, the Kingdom of Bahrain, the Kingdom of Morocco, and the Republic of Sudan.

Though the first layer and the overall spirit of the Abraham Accords is not about addressing the Palestinian-Israeli impasse, it still does allude to the conflict in the bilateral texts. Starting from the UAE-Israeli bilateral text, Palestinian rights are mentioned, but only in passing. Moreover, where it was mentioned in the text is even more revealing. Palestinian rights were only mentioned in the preface to the agreement, in a historical context and not part of the clauses that both the UAE and Israel agree on. What the UAE-Israeli document outlines and upholds is a broad scope of bilateral relations.

Furthermore, there is one element of the Accords which is noteworthy for its design to insulate the UAE-Israel agreement to entrench this relationship and shield it from any regional tremors that may affect the relationship—namely turbulence on the Palestinian-Israeli front through the boycott of support of any Palestinian cause that may threaten the Abraham Accords. Said differently, if any problem occurs, the UAE is committed to maintaining its relationship with Israel. This can be seen in clause 9 as it says: the “Parties undertake not to enter into any obligation in conflict with this Treaty […] in the event of a conflict between the obligations of the Parties under the present Treaty and any of their other obligations, the obligations under this Treaty shall be binding and implemented.”

When it comes to the bilateral agreement between Bahrain and Israel, it does mention that it is striving toward solving the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The entire text was a mere description of meetings between the respective representatives. So, one can say it was more of a declaration of principles rather than a clear-cut transactional process. In the entire text, Palestine was mentioned only once.

The Moroccan-Israeli text mentioned the Palestinian issue, but also in passing. It recalled a conversation between “Mohammed VI and His Excellency Donald Trump, on the current situation in the Middle East region, in which His Majesty the King reiterated the coherent, constant and unchanged position of the Kingdom of Morocco on the Palestinian question”. What makes the Morocco-Israel agreement stand out is that it was more clearly a trilateral agreement, where the United States was the one who offered the incentive of recognizing Moroccan sovereignty over the Western Sahara, as a substitute for any Israeli concessions to the Palestinians. In addition, like the UAE-Israeli agreement, it was mentioned in the preface.

The entire texts of the Abraham Accords, be it the American declaration of principles or the respective bilateral agreements, mention Palestine or the Palestinians only four times. Moreover, where Palestine was referred to in these respective texts within the broad framework of the Abraham Accords suggests it was used as an attempt to legitimize the normalization of relations—trying to make the Abraham Accords somewhat palatable to their respective citizens.

In contrast, the Saudi-based API has the Palestinian cause at its heart. While the entirety of documents pertaining to the Abraham Accords explicitly mention the Palestinian issue four times, the short API document mentions it once in the preface, but three times in the texts to be agreed upon. In addition, what the API mentions that the Abraham Accords do not are United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 and United Nations Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338. As a result, the API, while not perfect because it does not propose an explicit negotiation framework with time-sensitive milestones toward a resolution, still does have the ingredients for solving the core issue of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, which the Abraham Accords lack. Only the API has the legal ingredients and building blocks to sustainably address the core issue.

Misunderstanding Leads to Division

Saudi pragmatism toward Israel has often been conflated with a disvalue of Palestinian rights—this is certainly a misreading. As we navigate through the aftermath of the October 7 war, and the aftermath of the catastrophe that is still unfolding in Gaza, understanding the very nature of Saudi pragmatism toward Israel is crucial for having accurate working assumptions in a future peace process.

Such a misunderstanding is used by political elites in Israel to isolate the Palestinians further from regional normalization. Just before the eruption of the war, the Israeli prime minister tried to push the narrative that Saudis no longer care about the Palestinians, and that negotiations should negate any regard for Palestinian rights.

The October 7 war is yet another tragic illustration of the results of a faulty policy of “kicking the can down the road”, which is not only a failure, but a strategic mistake with consequences for regional security. That is precisely why the API must be re-articulated with more explicit language, in a more clearly defined peace process, with a more involved Saudi role on the negotiating table, as it, unlike the Abraham Accords, has the necessary building blocks and references for reaching a Palestinian-Israeli settlement.

Aziz Alghashian is a Saudi Arabian Fellow with the Sectarianism, Proxies and De-Sectarianization project (SEPAD) and the Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient (CARPO) as a researcher who focuses on Saudi foreign policy and Arab-Israeli relations. Alghashian was a lecturer of International Relations at the University of Essex from 2019 to 2021 and is frequently invited to provide analysis on international media outlets.

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter