Egypt’s Wildest Women

A study of Egypt’s art, culture, and politics of the 20th century is incomplete without a look at the leading ladies of the interwar period.

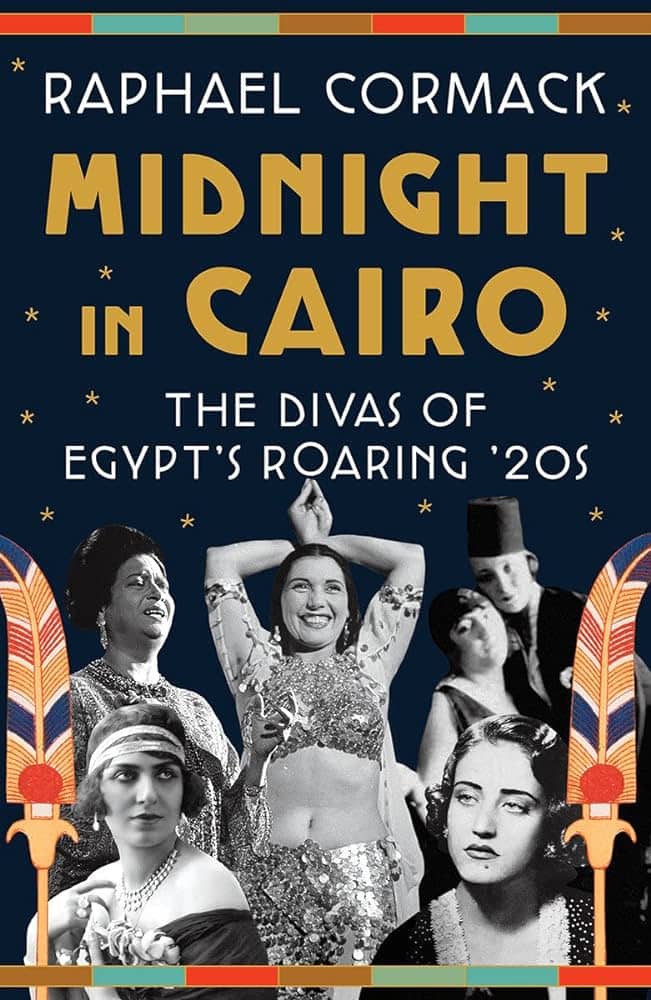

Midnight in Cairo: The Divas of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s. By Raphael Cormack. W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 2021. 384 pp.

Raphael Cormack’s newest book combines serious historiography and solid, extensive archival research with an approachable, engaging style. The result is a work that is at once instructive and entertaining—that opens new ground yet does so without the impenetrable terminology and abstract theoretical positioning characteristic of some contemporary scholarship.

Midnight in Cairo: The Divas of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s follows a timeline roughly delineated by the revolutions of 1919 and 1952. The book sheds light on a group of historical characters—only a few of whom are well known in Egypt for their artistic accomplishments or unusual lives—and shows that they were powerful agents of historical change. This may be Midnight in Cairo’s most significant contribution: to tell “an overlooked story of theatre, song, and dance that shows the modern Middle East from a different angle—not one dominated by wars, ‘intellectuals’, ‘great men’, or high politics, but by late nights in cabarets, wild music, and women calling for change.”

Cormack tells a fascinating story, and does so in a witty and understated tone. He eschews the salacious accounts, racist jabs, and arch tone of some historical fiction on Egypt. Yet it would be faint praise to focus only on Cormack’s efforts as a writer of accessible and entertaining history. He weaves a complex and rich social history, tracing connections between the evolution of social and political power dynamics, the appearance and transformation of institutions like the music hall, the spread of new technologies like the 78 phonograph record, and the diffusion of genres like the taqtuqa, light romantic songs that were popular at weddings and then gained prominence in the nightclubs of early twentieth-century Cairo.

While Midnight in Cairo is a fast-paced and easy read, Cormack does not give in to facile generalizations about his topic or the geopolitical context. Readers of Ottoman or Egyptian history may be unsurprised by erudite archive-based scholarship that nevertheless espouses orientalist tropes or leaves racist notions unquestioned; especially at the current moment, when some academics are casting fondly nostalgic glances back at the colonial period, it is heartening that Cormack manages to make accurate points about the real brutality of the British occupation of Egypt. Thus, he notes that “British accounts of the events of 1919 reveal noticeable gaps. They do not include the stories of soldiers opening fire on protestors, villages being burned to the ground, and the looting or sexual assault committed by soldiers who said they were trying to bring the country under control”.

Socially, Cormack documents all manner of transgressive behavior that would shock or at least astonish those who believe that Egyptian society was more narrowly conservative and morally straitlaced in the past than it is today. Clothing and behavior that flouted gender norms, sexually emancipated women entrepreneurs, political activism that called for the egalitarian redistribution of resources. Cormack offers his readers food for thought at every page. Nor does he paint an idealized picture of Ezbekiya, the hub of cultural and social effervescence as stated on page 57: “The dance halls and cabarets in turn-of-the-century Cairo … were obviously predicated on the commodification and exploitation of female bodies … but certain women … ended up with considerable control over their own lives and influence over others”.

Midnight in Cairo depicts widespread drug and alcohol use, women’s freedom to choose their sexual partners, a proliferation of new venues, artistic genres, and political ideas. One of Cormack’s talents lies in showing how the elements contributing to this effervescence reinforced each other and created an atmosphere of openness and possibility, even under the oppressive constraints imposed by colonial rule.

We meet renowned characters such as Shafiqa al-Qibtiyya, the dancing and singing “queen of [the] music hall stages in the 1890s,” whose “reputation for lavish spending was as famous as her colourful lifestyle … In [an] apparent dig at the Egyptian upper class, who overwhelmingly relied on Sudanese and Nubian domestic labour, she hired a staff of Italians and dressed them in the finest tailored suits. She is also remembered for her wild generosity with money … If people could not afford to pay for her to dance at their wedding, she would do so for free, and give them enough money to pay for a luxurious honeymoon”.

Another prominent figure is Mounira al-Mahdiyya, who “would appear onstage as a man,” playing roles that “almost always had the best songs. However, theatregoers regarded one of Egypt’s most famous cabaret singers’ decision to appear onstage as a man as unusual. They were used to men dressing as women to play female parts, but not the opposite. Notices in newspapers for the performances would often entice the audiences by announcing that ‘Mounira al-Mahdiyya is appearing in men’s clothes’”.

Perhaps less familiar even to those who know the main events of this period are characters such as Ibrahim al-Gharbi, “a Nubian brothel owner [who] went through the streets of Cairo dressed as a woman, wearing a white veil on his head, makeup on his face, and jewellery on his head, arms, neck, and fingers”.

These individuals, and many others like them, add depth and texture to Cormack’s nuanced and lively account. It is difficult to imagine that anyone would fail to enjoy it—from students to established academics, from amateur historians to those interested in cultural change and social movements. This book is that rare beast: a work of serious scholarship, written with wit and sensitivity by an author with a passion for his subject, so steeped in his archival material that he can bring it to graceful, enchanting life.

The paragraphs where Cormack describes the top singers’ fan clubs, for example, are particularly revelatory for those who imagined that only Um Kulthoum commanded fanatical loyalty in her audiences. “Although some Egyptians viewed these liberated women who were making their way into the entertainment industry at that time as corrupters of the country’s morals, many others idolised them.”

Cormack’s observations and anecdotes are situated within broader themes of social change, class relations, and women’s rights. The shift in political atmosphere in the post-World War II period is palpable, and Cormack chooses figures such as Tahia Carioca, dancer, actress, and political activist, to illustrate the ways in which the entertainment world adapted and contributed to this transformation.

As Egypt moved through the 1950s and into the 1960s, Cormack writes, the old world of interwar Ezbekiyya changed radically along with the rest of society. Cinema, radio, and television marginalized the cabarets in the city’s cultural life.

Midnight in Cairo leaves readers with a sense of awe at the optimism that prevailed in the interwar period; it seems impossible today to imagine that such hope once prevailed.