A Long View of the Middle East

Middle East historian James Gelvin speaks to Cairo Review editors Sean David Hobbs and Leslie Cohen about Middle Eastern current affairs, including where Syria is headed, and whether America’s moment in the Middle East has passed.

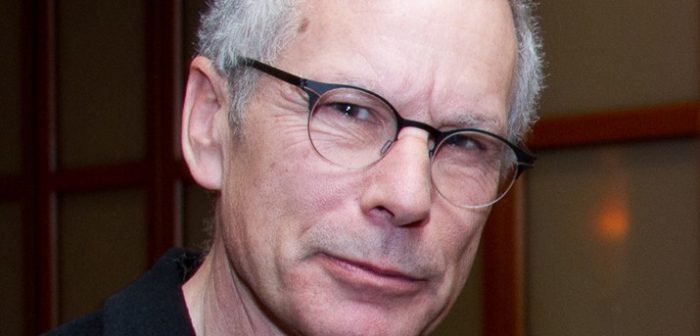

James Gelvin at the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) conference, Washington D.C., November 2014. Courtesy of James Gelvin.

James Gelvin, 67, is a leading historian and American scholar of Middle East history. His 2004 book, The Modern Middle East: A History, which surveys five hundred years of Middle East history, is a core text in Middle East studies.

Gelvin has written extensively on the making of the modern Middle East, taking a particular interest in country nationalisms and cultural history. He has produced notable works such as The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War (2005), The New Middle East: What Everyone Needs to Know (2017), and The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know (2012), among others.

Given Gelvin’s extensive knowledge of the region, he is one of the most prominent pundits on Middle Eastern affairs. As a historian commentating on current events, Gelvin believes he has a special responsibility, despite his expectation that not much will change in the Middle East. “[I understand the] Saudi tail will continue to wag the American dog, governments in the region will continue to jail prisoners of conscience, and Syria and Yemen will continue their descent into hell,” he once wrote, “However, to paraphrase former Czech dissident Václav Havel, appalling circumstances demand clarity, accuracy, and directness from those equipped to provide it.”

Gelvin spent most of his life teaching Middle East history. After almost two decades at the University of California at Los Angeles, Gelvin was awarded the 2015 Middle East Studies Association Undergraduate Education Award.

Among other distinguished positions he held were co-director of UCLA’s Center of Near Eastern Studies, and the Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al-Nahyan visiting professor at the American University of Beirut.

Cairo Review editors Sean David Hobbs and Leslie Cohen spoke with Gelvin on July 2, 2018.

CAIRO REVIEW: Why has Syria turned out the way it has?

JAMES GELVIN: We tend to look at all the uprisings through the lens of Tunisia and Egypt, and that’s a problem. There’s a real difference in the way the uprising in Syria broke out and the way the uprising broke out in, say, Egypt. The uprising in Syria began like the uprising in Libya. It was spontaneous, broke out in multiple locations, and it was leaderless. There were three factors in general that made the Syrian uprising end up the way it has: the extent to which it was militarized, the extent to which it was sectarianized, and the extent to which it became a proxy war.

In the beginning, the Syrian government relied on its security services to put down the uprising. But as the uprising leapfrogged from city to city, town to town, the government brought in the army to destroy the resistance. The government laid siege to neighborhoods and cities, then bombed and shelled the besieged areas indiscriminately to destroy the opposition. Armed members of the opposition—mostly deserters from the Syrian army—who had been protecting unarmed demonstrators from government snipers, had to flee into the countryside where they regrouped as the Free Syrian Army. This severed the connection between the military and political wings of the opposition. The military wing came to dominate the uprising and the civilian wing atrophied.

The government sectarianized the conflict to ensure that a society that had been polarized between the government and its supporters, on the one hand, and opponents of the government, on the other, would repolarize along sectarian lines. Seventy-five percent of the Syrian population is Sunni Muslim; the remainder consists of Alawites (who form the core of the ruling group), Christians, and other minorities. While the opposition initially included members of all sects, the government attempted to identify it with the most radical elements of the Sunni community to break it up.

They did this in several ways. As soon as the uprising broke out, the regime labeled its opponents Salafis, terrorists, jihadis, and agents of Saudi Arabia. To ensure this would be a self-fulfilling prophecy, the regime released Salafis, Islamists, and jihadis, including those associated with Al-Qaeda, from prison.

Many ended up in the Al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria or in ISIS. The regime also polarized society through violence. It organized armed “popular committees” to protect Alawite villages, and it equipped pro-regime vigilantes with knives and clubs for use in street battles with mostly unarmed protesters.

The regime strategy worked, and among the minority population the government achieved what the United Nations Development Programme has called “legitimacy blackmail.” In other words, minorities came to see the government as their only protection from the majority Sunni population.

Finally, the Syrian civil war has been difficult to resolve because it became a proxy war. Russia, Hezbollah, and Iran support the government; the West, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and others have supported the opposition. Every time one side looked as if it were gaining the advantage, the patrons of the other side would increase their support to offset that advantage. This has killed the possibility for a negotiated settlement, which depends on what political scientists call a “mutually hurting stalemate” among belligerents. All sides have to see they have nothing to gain from further fighting.

How the proxy nature of the war has worked can be seen in the history of the conflict. In the summer of 2015, the government was on the ropes, mainly as a result of Western and Gulf assistance to the opposition. The tide turned after the Russians intervened on the side of the government in the fall of 2015 and began their bombing campaign. And that’s where we are now.

CAIRO REVIEW: So, it appears that Al-Assad and his allies are headed toward victory.

JAMES GELVIN: There’s no doubt that Al-Assad is on the road to victory. Let’s first eliminate some possible endgames. Since this is a proxy war and each side is supported by outside powers, it is unlikely that either the Syrian regime or the opposition can completely eliminate the other. Syria will not be divided, since neither the outside powers nor Syrians want that. There is no possibility of a negotiated settlement. Now that the government holds 99 percent of the battlefield cards, why would it want or need to negotiate?

The most likely end is what former United Nations and Arab League mediator Lakhdar Brahimi called “Somalization.” As in the case of Somalia, Syria would have a single government, which will reign, but not rule, over the entirety of its territory. It would have a permanent representative to the United Nations, issue passports and postage stamps, and even, if it so desires, send a team to the Olympics. As in the case of Somalia, armed militias would control swaths of territory outside the control of the government. There will certainly be a devolution of power downward to the local level in many places, but this system will likely resemble warlordism, not democracy. And the government will be the largest and most powerful warlord.

But even though the government is likely to be the biggest beneficiary of this outcome, what’s Al-Assad going to win? We are, after all, talking about a country that’s suffered at least 500 thousand deaths, with close to half the prewar population displaced, where more than 80 percent of the population is below the poverty line, and almost half of all children of school age are not attending school. We’ve seen a reappearance of diseases that had been eradicated, like polio. You have an unemployment rate of close to 60 percent, with about one-third of those employed working in the war economy. There’s been about $180 billion worth of damage to infrastructure. And who will fund recovery? Russia? Yes, it’ll be a government victory, but a Pyrrhic victory at that.

CAIRO REVIEW: Is there a way that the people of Syria can eventually move toward a more representational government? Economic freedoms? Perhaps with some areas not controlled by the central government, but where the country comes through what looks like a brutal peace?

JAMES GELVIN: I’m afraid I don’t see that happening. When people talk of economic freedom these days, they usually mean the adoption of neoliberal economic policies, like those at play in the United States. Neoliberalism has been nothing but a big, fat failure everywhere it has been introduced in the Arab World. Instead of free market capitalism, it has brought crony capitalism. By destroying the social safety net, it has severed the bond connecting governments with their citizens. Instead of integrating the Arab World into the global economy, the Arab World remains the world’s second-least globalized region. Before the uprising, the Syrian government tried an economic policy it called a “social market economy,” that was, in fact, written by the IMF [International Monetary Fund]. It led to minimal growth but widespread corruption and grumbling.

In terms of politics, I doubt there will be any movement toward a more democratic system. Any voices for democratic change will be silenced, if they haven’t been already. The population has been totally brutalized, and very likely the psychological effects of the war will keep it demoralized. Things may simmer below the surface, but for now most of the population is focused on little more than survival. I don’t see democracy on the horizon, not in five, ten, twenty years. Then again, I didn’t see an uprising on the horizon either.

CAIRO REVIEW: What are the prospects for the “Deal of the Century” and such a peace under the Donald Trump administration?

JAMES GELVIN: I’m doubtful that there will be an Israeli–Palestinian peace under Trump, or frankly in the foreseeable future for a number of reasons. The most important of these is that the Israelis don’t want a deal. The last thing [Benjamin] Netanyahu wants is to see his coalition fragment, which it would in the unlikely event of his offering to compromise on territory or settlements. So it’s easier for him to not make a deal. Under [Barack] Obama he pretended under pressure that he was interested in a two-state solution, but under Trump he won’t even have to pretend. There won’t be any pressure. And the fact that the Palestinian national movement is hopelessly divided is another disincentive.

Two other factors are important to consider: First, you have the most pro-Israel government in American history, which will not say no to any Israeli action, no matter how outrageous. Would Trump say anything were the Israelis to annex the West Bank? He would probably applaud it. This is the guy who moved the American embassy to Jerusalem, after all.

Second, the Israelis are doing quite well for themselves regionally, so they have no incentive to reach an agreement with the Palestinians. There used to be a time when Saudi Arabia or some other state would hold out the incentive of diplomatic ties or trade. Now Saudi Arabia is dropping hints that normalization may be in the future, and other Gulf nations have warmed up to Israel. This is because Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf countries are on the same page when it comes to Iran—a problem they’ve inflated for their own purposes—and Saudi Arabia and its allies would be more than willing to betray the Palestinian cause for the strategic depth an alliance with Israel would bring.

CAIRO REVIEW: Is the American moment over in the Middle East?

JAMES GELVIN: There really are two questions here: Is the American moment over in the Middle East, and is the American moment over as the “indispensable” broker of an Israeli–Palestinian peace? In terms of the first, the answer is both yes and no. During the Cold War, the United States and its allies were linked in a common purpose: to maintain the status quo in the region.

This meant not only blocking the spread of Soviet influence but blocking the emergence of any regional power that might upset that status quo. The United States was quite successful in both, mainly because America’s interests were the interests of its allies, and its allies took on much of the policing of the region while the United States gave them support from afar. True, there was the occasional American foray into the region—Lebanon in 1958 and 1983, for example—but for the most part Israel acted as America’s proxy in the west and Saudi Arabia and prerevolutionary Iran in the Persian Gulf. Alignment with the United States became the rule and alignment with the Soviet Union became the exception.

You have to remember, however, that even during the Cold War the United States was anything but omnipotent. There were outliers to the American order—for example Syria, Libya, Iraq, Yemen, and for a time, Egypt. There were significant failures (Iran in 1979) and times when allies went rogue (Israel in Lebanon in 1982). There were also a number of surprises, like the 1973 [Arab–Israeli] War and the oil price revolution. The first brought the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war, the second nearly collapsed the global economy. This is what I meant by “yes and no.” But in the main the premise of your question is correct: if measured in American terms, the Cold War represented America’s moment in the Middle East.

With the end of the Cold War, that community of interest between the United States and its allies was gone. Furthermore, as the sole superpower the United States fell under the spell of imperial hubris, overreaching in Iraq and elsewhere. The result was Obama’s Middle East policy. Obama believed the United States had expended far too much blood and treasure in the Middle East under George W. Bush. The Middle East has no comparative advantage in anything, and suffers from multiple, deep-seated problems. Its only major exports are oil and unemployed youths.

For Obama, Asia would be the epicenter of global competition in the twenty-first century. His policy was to get the United States out of the Middle East and instead “pivot to Asia.” Obama wanted the United States to lighten its footprint in the region and to tamp down conflicts: hence the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq, the Iran nuclear deal, and attempts to restart negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians. This is not necessarily a bad thing for the United States, but it led to two inevitable results: the loss of American influence in the region, and a scramble by mostly regional players to strengthen their position.

That’s where we are now, only Trump’s made everything even worse. By basing his policy on doing the opposite of what Obama did—by being the “Unbama”—he’s made American foreign policy a wholly owned subsidiary of Israel and Saudi Arabia, and involved the United States in their paranoid fantasy that the biggest problem in the Middle East is terrorism and Iran is the biggest purveyor of terrorism.

CAIRO REVIEW: And about America being a peace broker?

JAMES GELVIN: American “mediation” of the various conflicts involving Israel has done as much harm as good and still hasn’t resolved the conflict that is at the root of the overall problem, which is between Israel and the Palestinians—not Israel and the Arab states. Whenever the United States intervened in the conflict it has been because U.S. interests were at stake, and the United States naturally intervened primarily to further those interests whatever the cost.

Let me give you an example: at the end of the 1973 war, Israeli and Egyptian commanders engaged in what became known as the “Kilometer 101 Talks,” which began with the disentangling of forces in Sinai, then moved on to more substantive issues. Where those talks would have gone will never be known, because the United States—in fact, Henry Kissinger—put pressure on [prime minister] Golda Meir to break them off. Kissinger wasn’t particularly interested in peace—he was interested in enhancing America’s position in the region, and he believed any talks between Israel and its neighbors had to include the United States. Hence, Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy made the United States indispensable as a mediator but ended up resolving only limited issues.

The United States has never initiated negotiations that panned out. The two lasting peace treaties signed between Israel and its neighbors came about as a result of local initiative, as did the Oslo Accord. So I guess in answer to your question, under Trump the United States has irrevocably lost its position as mediator in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but maybe that’s not a bad thing.

CAIRO REVIEW: Do you see the divide between Saudi Arabia and Iran as connected to some of the failures of the Obama administration?

JAMES GELVIN: I think that at its root there are three reasons why Saudi Arabia has become as paranoid as it has and felt that its best option is to gather its closest allies around it, including the United States, to form a coalition against Iran.

The first is the uprisings, which threatened other status quo powers in the region, which were Saudi allies. Second, the Obama administration frightened them by pulling back and telling them they would have to “learn to share the neighborhood” with the Iranians, something they desperately wanted to avoid. And third, the extraordinary drop in oil prices between 2014 and 2016, which forced them to draw on past earnings to maintain solvency and continue to pay off their population in exchange for their compliance.

Saudi Arabia and Iran operate on different models of governance, have different goals in the region, and have different survival strategies. Saudi Arabia promotes submission to the dynasty at home and adherence to the status quo abroad. The Saudi government does not like to see Islamic activism anywhere because it threatens that status quo. Saudi Arabia has also been aligned with the United States, the dominant status quo power in the world and the guarantor of the Middle East state system.

The profile of Iran is the polar opposite of that of Saudi Arabia. Iran was a staunch ally of the United States in the region before the revolution of 1979. Then, Iranian foreign policy flipped 180 degrees. The newly established Islamic Republic viewed itself as a revolutionary power intent on shaking up the status quo and defying and rolling back American imperialism. While Iran has largely backed away from spreading the revolutionary model in its rhetoric and actions, it has taken advantage of cracks in the system, particularly those borne of the Arab uprisings.

CAIRO REVIEW: What do you think is the future of human rights in the region?

JAMES GELVIN: There are global norms of human rights to which the region will move in the future. I’m not optimistic about that in the short term or even midterm, but overall, it’s going to happen. There’s enough of a political constituency to keep this on the agenda.

The United States began pushing for human rights in the 1970s alongside neoliberal economic policy simply because the two were compatible. You need individuals able to make autonomous decisions, have access to information, form associations among themselves, and represent their interests in government to have neoliberalism. And the United States used human rights as a stick to beat both the Soviet Union and the Third World during the 1970s.

The United States was growing increasingly paranoid of the Third World flexing its muscles in global economic relations, blocking the West’s access to raw materials, and demanding a place at the table. So the United States began to fight back with human rights, and one of the first places it did so was the Helsinki agreement of 1975. While neither the United States nor the Soviet Union that signed on to it cared about the human rights language in the agreement, populations in the Soviet bloc used it as a stick with which to beat their governments.

In the Middle East, the United States asked its allies to establish toothless human rights councils. It didn’t do this because the United States thought they would be effective but for domestic American consumption. Now, everybody knows the Saudi government doesn’t care about human rights, and yet there is a Saudi commission that is supposed to monitor human rights in Saudi Arabia. The citizens of Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arab World do, however, care. To monitor the monitors, Arabs founded their own human rights groups. The first of these was founded in Tunisia two years before Human Rights Watch was founded.

In other words, populations use human rights in the Middle East in exactly the same way that populations in Eastern Europe used human rights: as a stick with which to beat their governments. And this is how it became part of the political discourse in the region. Governments that would never even think of giving in to their populations on anything at least pay lip service to human rights. So win or lose, human rights has come to be embedded in the political discourse of the Arab World. This is the only cause I have for optimism.