Mustafa Amin’s Legacy Revived

Mustafa Amin was a touchstone for a generation of journalists who valued a freer and more truthful school of journalism. His recently donated private library offers a rare glimpse into his professional life.

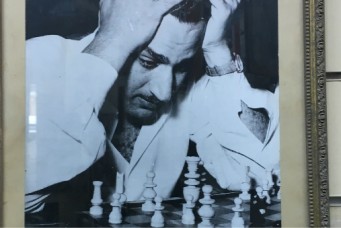

Mustafa Amin writes an editorial about love in Akher Saa magazine. Issue: Nov. 1, 1960. All photos in this article are courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library.

Mustafa Amin—dubbed the “father of modern Arab journalism”—is widely considered one of the greatest newspapermen of the twentieth century. A renowned journalist, columnist, and author, he is also remembered as a longtime agitator for the way he transformed journalism and pushed for free speech in Egypt and the Arab World. Between the 1930s and 1950s, Amin also created a media empire by establishing and boldly building up his own publishing house.

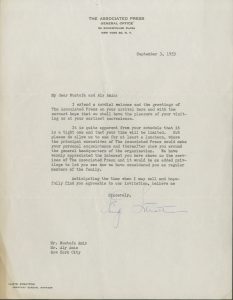

Twenty years after his death in 1997, his wife Isis Tantawi donated over five thousand books from his private library to the American University in Cairo. Beyond the wealth of articles and published work, the collection includes a treasure trove of draft articles, publications, and personal letters, among them an Associated Press telegraph inviting Amin to a luncheon with AP executives. From Amin’s personal archives at the Rare Books and Special Collections Library, there are original documents, including a copy of his will, diaries, drafts of books and television soap operas, and personal correspondence with many icons of that era such as the late Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

His works bear witness to his versatility covering the turmoil and drastic changes of the twentieth century—from the Cold War to the pangs of Arab nationalism and the era of decolonization, from feminism to regional and global politics, as well as philanthropy. Despite Amin’s almost fanatic followership in Egypt and the Arab World, he was a highly controversial figure. He advocated Western-style democracy and free press and was an outspoken liberal at a time when Egypt had more Soviet leanings.

Amin and his twin brother, Ali, found their calling in the home of their great uncle, Saad Zaghloul, a revolutionary political leader who fought against the British. At the precocious age of 14, they launched a series of student papers and magazines at school. “I released a magazine in school and the principal punished me,” wrote Amin. By the time he graduated from the American University in Cairo in 1934, he was already penning a magazine column.

His writings quickly garnered him not only a large readership, but also caught the eye of those in power. In 1944, for example, Amin published a diary-style magazine article titled “Thirty Years A Journalist” recounting memorable incidents in the last thirty years of his life. In one entry of this archival piece, Amin discussed his “ongoing war” against Mustafa El-Nahhas, the prime minister of Egypt at the time. Amin even quoted famed Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum warning the prime minister of a popular backlash against the government if he were to arrest Amin over his writings. Egyptians, she said, would “curse the government if they are deprived of reading his articles!”

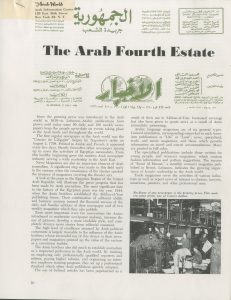

However, the Amin brothers’ greatest contribution was to the field of journalism. When they left a magazine job to start the Saturday weekly paper Al-Akhbar Al-Youm, it was their first time experimenting with the idea of free press. Their main goal was to establish journalism as a respected profession in the Arab World and set the benchmark that other Arab publishers quickly adopted. For example, the Amin brothers insisted on employing only professional and qualified staff and paid them appropriate salaries.

The AUC archives reveal the name of one of the Amin brothers’ biggest inspirations in journalism: Mohamed Al-Tabii—dubbed the “Prince of Journalism”—who was a leading Egyptian political writer and journalist in Egypt and the Arab World as well as the editor of a cultural-turned-political magazine called Rosa Al-Yusuf. Amin and his twin brother were Al-Tabii’s students when they worked at the magazine and then followed him to Akher Saa magazine, which they acquired almost two decades later.

Throughout, they idealized free enterprise and speech, which became entrenched principles in their style of journalism. In an interview found in the archives with student journalist Mostafa Kamal Ahmed, Amin said that he believed the reason behind the success of Al-Akhbar Al-Youm was its pursuit of its mission regardless of popular opinion. This was the mantra Amin followed as he went on to establish a daily and acquire two weeklies and a youth magazine—even when Nasser nationalized the press in the 1960s. It was an arduous task that took a toll on him; in one journal entry dated in 1945, he writes, “My sleep hours have decreased. I have become old in my youth”.

Amin was first jailed briefly in 1939 for criticizing King Farouk. However, he is most known for his altercations with Abdel Nasser in the 1950s for which he was jailed twice, then again in 1965 for nine years on charges of espionage. Amin was arrested while having lunch in Alexandria with U.S. CIA agent Bruce Odell. Despite being handed a life sentence, president Anwar Sadat released him in 1974 for health reasons.

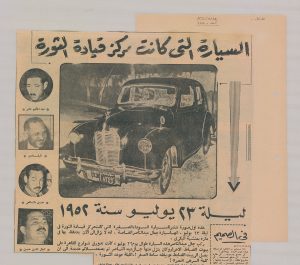

The archives don’t touch upon Amin’s life or works in jail—which were later published in a book titled Year One Jail in which he alleged mistreatment—or even his life afterward. The archives tackle Amin’s early life, which uncover his often-overlooked side. For instance, there are articles that reveal mutual respect between Amin and Abdel Nasser, even after Amin was jailed in the 1950s. Amin mentions his admiration of Abdel Nasser’s “genius”. His support and active involvement in the anti-colonial movement put Amin in a bind: while he seemed a public enemy to Nasser, many of his works praised and analyzed the 1952 coup—with one article calling Abdel Nasser’s car the commanding center for the “revolution”.

Mustafa Amin was a touchstone for a generation of journalists who valued a freer and more truthful school of journalism. His influence on public life is not any less impactful as he popularized anEgyptian Valentine’s Day, which falls on November 4, and advocated celebrating Mother’s Day. He led several appeals in his papers to help those in need. The human impact of his life and work reverberate to this day.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter