Sustainable Humanism Needed

COVID-19 has become a central election issue, but to overcome this urgent health crisis America needs to tune out the echo chambers that repeat medical misinformation and conspiracies.

COVID-19, climate change, and racism all have some unfortunate similarities. They are global crises and they all have a death toll. Each causes maximum harm to the least well-off in society, and they all lay bare our structures of social inequality. And, they all are made worse by sometimes purposeful and strategic misinformation.

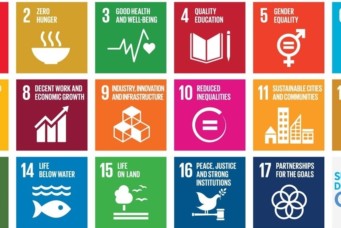

To deal with these and other crises, we need a “sustainable humanism”. On a basic level, sustainable humanism means that we care about and value one another, which in the end sustains the welfare of communities. We need to see the dignity and worth of people and care about their future. To fight racism and the spread of the virus and bend the curve of rising global temperatures, we need to care about other people and act in a way that builds integrity, trust, and well-being.

The picture becomes more transparent when thinking about groups that either want these crises to continue, or at best, do not want to take steps to ameliorate them. These groups have some interesting similarities, much of which surrounds preserving privilege that harms others.

Beating the pandemic requires us to take precautions around congregating and wearing masks, but some groups have protested these measures, and often these protesters are armed. Let’s call them “anti-lockdown protesters”. Anti-lockdown protesters are angry. Their anger is fed through echo chambers that repeat medical misinformation and conspiracies. They believe their personal freedom is harmed and that the government is using the virus to control people and foster tyranny. Notably, anti-lockdown protesters are predominantly Caucasian. The Washington Post reported in May that in addition to attracting militia groups and white supremacists displaying swastikas and the confederate flag, these protests

… have been supported by conservative megadonors, have ties to a host of darker Internet subcultures — people who oppose vaccination, the self-identified Western-chauvinist Proud Boys group, anti-government conspiracy theorists known as QAnon, and people touting a coming civil war.

This description also seems to describe counter-protesters to the Black Lives Matter protests, some of whom have appeared fully armed with semi-automatic rifles and tactical paramilitary gear. These counter-protesters have attracted white power groups and have used their vehicles as weapons, driving into crowds. To resolve systemic racism, we need the opposite behavior, that is we need—individually and socially—to see people of color as humans who possess dignity and worth.

When it comes to climate change, we need to de-carbonize our economy. This will have costs—though most analysts believe those costs will be far outweighed by benefits and damages avoided. Bearing these costs will require us to think about and value the lives of others both at home and abroad. However, if we continue to fail to reduce greenhouse gases, insecurities and threats will multiply and the people affected most will be the poorest on our shared planet.

Sustainable humanism recognizes the value of these lives and the suffering that the poor feel—and will feel in future generations—and requires us to act to lessen the loss and damage already underway. Importantly, we see the need to value non-human life as it is also threatened by climate change. Scientists agree that climate change will bring explosive biodiversity loss and extinctions which will have a chain reaction causing other extinctions. If this were the only fact of climate change impacts, we would still be obligated to avoid abusing the intricate web of life around us because, as many Indigenous traditions assert, our ecology constitutes part of what being human means.

In contemporary sustainability studies, we speak of “social-ecological” systems that mutually reinforce and inform one another. We see that humans would not exist without the ecological systems within which we have evolved. We are co-constitutive with our ecological systems even though humanity has shaped the Earth so extensively that researchers refer to this time as being the Anthropocene (which means a period of time that is fundamentally human-influenced). Embedded in this Anthropocene concept is the example of climate change. Some 97 percent of climate scientists agree that the average global temperatures are rising, due mostly to human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases, and that this event will have many negative impacts such as species extinctions.

However, there has been a thirty-year program organized as a social “countermovement” to cast doubt on climate science without doing any science of its own. This is because climate denial is not about research or fact gathering, but instead it is about politics. Climate denial is animated by a fear of loss of power and privilege that is imagined in the transition from conventional energy sources that have fueled modern progress and industrialization. The Climate Change Countermovement disseminating misinformation was started in the United States, and is primarily a U.S. phenomenon, with some adherents in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries countries like Australia and Canada.

The idea of de-carbonizing the economy fundamentally scares climate deniers because it threatens their global position and privilege, as well as their lifestyle of comfort. This is a lifestyle that is only enjoyed by the high classes in Western nations like the United States and the United Kingdom.

The fact that the Climate Change Countermovement is not significantly organized outside of the English-speaking world should be telling. And, yes, the countermovement supporters are mainly white. Surveys analyzed by McCright and Dunlap (2011) find “that conservative white males are significantly more likely than are other Americans to endorse denialist views … and that these differences are even greater for those conservative white males who self-report understanding global warming very well.”

Why does this view gain traction? It is likely because of echo chambers of digital misinformation that go unchallenged. Active members of these echo chambers or silos share information within their homogenous community which supports narratives similar to the Black Lives Matter counter-protestors.

Between the triple crises, these opponents to meaningful solutions fear losing their individual freedoms and white privilege. Their opposition has been inward looking and pushes its believers toward an exclusion of non-whites. This opposition results in system-defending behavior which exacerbates each crisis. In order to push back against this opposition, we must focus on public policies that value the inherent worth of all humans regardless of skin color.

I argue that we need a new humanism to address each crisis. This new humanism will help us in the future as crises arise such as growing unemployment. I call this new humanism “sustainable humanism” because one hopes this concept can be the moral compass that will maintain humanity in the coming years.

To be sure, past iterations of humanism have been problematic, indeed chauvinistic in their focus on the Enlightened “man” and a masculine, undiluted, all-powerful “reason”. This kind of eighteenth and nineteenth century-based chauvinism is not sustainable. We have seen many examples where this concept of Enlightened “reason” is simply a cover for a white, male justification of Western consolidation of global power. We certainly do not want to resurrect that kind of humanism, but instead build a new humanism that works against prejudice and the abuse of power; a humanism that sustains all communities.

During the pandemic, countries like New Zealand and Iceland took approaches that (1) firmly acted on the best medical science, and (2) were based on valuing human wellness. The prime minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern, openly embraced a humane, public empathy meant to commiserate but more importantly build trust. Both countries forcefully built the capacity to track down anyone thought to be exposed to the virus and then compelled those at-risk people to quarantine for two weeks. The result was a minor inconvenience for the public good. These and other countries with similar responses—interestingly led by women—have been spared the worst of the virus.

In the United States, meanwhile, we have held the economy as our central priority and indecisively squabbled about how or if we should substantially support the unemployed, small businesses, and state and local governments. That has not been a sustainable approach. If we valued the dignity and worth of people, we would prioritize their lives and welfare.

In New Zealand, twenty-two people have died of the virus as of this writing in early September 2020. Iceland has lost ten people. In the United States, more than 180,000 people have been sacrificed for a skewed moral compass empowered by leaders who do not value science. I am making a normative argument, and reasonable people can disagree over my proposition, but ask yourself this: if our beliefs inform our actions, what beliefs do you think would be able to solve virulent crises like racism, global warming, and the coronavirus?

Dealing with crises requires us to be humane—that we minimize harm and suffering and that we are good to each other. That is utterly inconsistent with racism and leaving people to starve—whether from unemployment, climate change, or systematic inequity. Sustainable humanism does not give us a detailed agenda or policies but does perhaps give us some parameters to discuss these things. This is a discussion that should be inclusive, well-informed, honest, and kind.

Dr. Peter Jacques is a Professor of the School of Politics, Security, and International Affairs & the National Center for Integrated Coastal Research at the University of Central Florida. Jacques specializes in global environmental politics and sustainability, and has published five books and many research articles on various related issues.

This article was written as part of the Addressing Global Crisis Project (AGC), which is run by the University of Central Florida’s Office of Global Perspectives & International Initiatives (GPII). AGC examines how governments, individually and collectively, deal with pandemics, natural disasters, ecological challenges, and climate change. AGC is organized around five primary pillars: (1) delivery of services and infrastructure; (2) water-energy-food security; (2) governance and politics; (4) economic development; and, (5) national security. Through its global network, AGC facilitates expert discussion and features articles, publications and online content.

Peter Jacques is professor at the University of Central Florida’s (UCF) School of Politics, Security, and International Affairs. He is also an Earth System Governance Senior Research Fellow at UCF’s National Center for Integrated Coastal Research. His most recent books include Environmental Policy Paradox and Sustainability: The Basics. On Twitter: @PeterJJacques1.

Read More