Palestine, an Arab Issue

Arab leaders are confronted by the peace process’ legacy of failure. Today, they face the urgent task of achieving a two-state solution before it is too late.

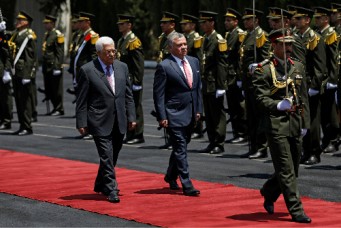

Arab leaders attending an Arab League emergency meeting in Cairo, Dec. 21, 2013. Mohammed Bendari/APA Images/Zuma/Alamy

The Arab-Israeli conflict, particularly its Palestinian dimension, is the longest ongoing conflict in modern history. It has witnessed the loss of invaluable human life and of vast resources beyond reason. This conflict has been the focus of numerous peace processes, with the record of failure far outweighing the few cases of success.

During the formative stage of the conflict, the adoption of the 1947 partition resolution by the UN General Assembly, and the establishment of the State of Israel at the expense of the Palestinians, the Arab region itself was undergoing major transformation. New leaders were confronting the challenges of nation-building as the era of European colonialism gave way to the establishment of new states and a new phase of nationalist politics. President Gamal Abdel Nasser is rightly credited for championing the Arab case against Israel while raising Egypt’s posture regionally as a leader of the Arab World and internationally as a co-founder of the Non-Aligned Movement. However, he is also held responsible politically for the debacle of the 1967 war, which broke the Arab World’s confidence and shattered its image. His successor Anwar Sadat took the courageous position of initiating the 1973 October War to recover Arab lands occupied by Israel, and to embrace a new direction for Egypt’s foreign policy that focused on negotiating with Israel. However, by signing a peace agreement with the Israelis, Sadat diminished the negotiating weight of the Arab side in the overall conflict, and thus derailed, or at least postponed, any possibility of a comprehensive Arab-Israeli peace. President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak succeeded in restoring Egypt’s position as the central actor in the Arab World, and reestablished a sense of stability and security, both in Egypt and the region. He did this in his first decade in office while safeguarding peace with Israel and upholding Egypt’s commitment to the ultimate goal of comprehensive peace. He did not, however, substantively contribute to widening the scope of Arab-Israeli peace, despite Egypt’s consistent role in hosting numerous Palestinian-Israeli negotiations, nor did he offer a clear vision for the future of the Middle East.

Leaders in Syria and Jordan, each for their own motives, supported Palestinian aspirations, especially when they coincided with their respective interests, which was not always the case. The Syrian government, the most vocal amongst the so-called rejectionist states, spoke loudly about a comprehensive peace, but never engaged seriously in the various peace efforts for addressing the conflict, beginning with the Geneva conference immediately after the October War. Rather than participate in a common Arab negotiating effort, Syria wanted the Arabs to join a Syrian-led rejectionist front against Israel. Having adopted the least constructive posture toward peace, Syria in fact undermined Palestinian efforts toward a negotiated settlement with Israel.

The Jordanian monarchy had the unique challenge of preserving Jordanian identity with a diverse population the majority of which was of Palestinian origin. That was an ever-present factor that limited Jordan’s political and diplomatic options vis-à-vis the conflict, often unable to reconcile the need to engage with Israel in peace negotiations to ensure the stability of the Kingdom, and the constant pressure of the Arab rejectionist front to adopt a more hardline approach toward Israel.

A House Divided

As a result of this mix of competing, and often conflicting, Arab motivations, the story of Arab involvement in the conflict is replete with inter-Arab rivalry that distracted and weakened the Arab negotiating position. The eviction of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from Beirut under Syrian pressure during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the Jordanian-PLO confrontation of 1970–71 (befittingly known by the infamous label of “Black September”), and the near military confrontation between Syria and Jordan during that same period are only the most prominent episodes of the inter-Arab rivalries that undermined the Palestinian cause in the conflict with Israel.

Though Arab politics could have been more supportive of the Palestinian cause, under no circumstances does the onus for the failures we have witnessed fall solely on the Arab side. Israeli leaders from Prime Ministers David Ben-Gurion to Benjamin Netanyahu, and all of those in between, pursued opportunistic, mostly expansionist, policies based—almost without exception—on a balance of power philosophy. This contradicted the very premise upon which the state of Israel was established by the United Nations. UN General Assembly Resolution 181 adopted seventy years ago this month envisioned the establishment of a Jewish state alongside an Arab state. The hallmark of Israel’s policy since then has been the adamant resistance to the creation of a Palestinian state on any portion of the land of historic Palestine between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River. Even the tentative moves by Prime Ministers Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres to accommodate Palestinian aspirations were ambiguous at best and short-lived with the assassination of the first, and the political decline of the second. The onus for the failure of Palestinian-Israeli peace efforts falls squarely on Israel.

The Palestinians no doubt also bear their share of responsibility. The constant infighting between the different Palestinian factions was highly detrimental to their cause, and rendered them easy prey to their adversaries. Such a verdict should in no way detract from the manifest legitimacy of Palestinian claims, the justness of their cause, or the undeniable reality of Israel’s ultimate responsibility for the perpetuation of what is now the longest military occupation in modern history.

In their long and varied involvement, the superpowers also prioritized their own interests over the imperative of peace. This was true in equal measure for both the former Soviet Union and the Russian Federation today, and the United States, especially given the fact that the peace process has been a mostly U.S.-dominated affair since the late 1970s.

A Final Chance for Peace

As the decades passed and frustration accumulated, violence was the inevitable, if not justifiable, byproduct of Israel’s deepening occupation of the West Bank and Gaza strip, its demeaning treatment of the Palestinians, and the repeated failure of the “peace process,” which served more as a cover for Israel’s occupation than as a genuine attempt at reaching a settlement. There were innumerable reasons for the failures we have witnessed, much of which can be attributed to the failure of both sides to the conflict and those outside powers that have sought to intervene on their behalf. The penchant for substituting double standards for principle, together with the massive imbalance of military and political power between Israel and the Palestinians, worked to undermine the prospects of a just and lasting settlement to the conflict.

Some progress was nonetheless achieved. Most notable in this regard is the creation of the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Gaza, the clarity with respect to the settlement of the core issues of Israeli-Palestinian peace (Jerusalem, borders, security, and refugees) as a result of countless rounds of negotiations, and the widespread recognition that the Palestinian issue remains at the heart of the region’s conflicts and instability, even if current regional crises continue to dominate the headlines in Syria, Libya, Iraq, and elsewhere. Whatever their merit, such achievements are in no way commensurate with the toll of human suffering, the numerous missed opportunities for advancing peace, or Israel’s relentless settlement drive that is gradually eroding the prospects for a two-state solution to the conflict. Perhaps the one “achievement” if one can use such a term given the grim reality, is that after decades of occupation, the human toll is much clearer today than ever before. No less stark are the alternatives to peace. We are at a crossroads between peaceful resolution or future generations of strife and conflict about identity and equality.

If we choose the path toward a peaceful, negotiated resolution for the conflict, then there is no viable solution except the establishment of two states, Palestine and Israel side by side. The Palestinian state will have to be based on the 1967 Arab borders with Israel, with minor exchanges of territory for the sake of unifying villages and contiguity between Gaza and the West Bank. Jerusalem will have to be the capital of the two states, with cooperative arrangements adopted for management of overlapping services or connectivity. The right of return or compensation of Palestinian refugees will have to be recognized by Israel even if refugee resettlement will be mostly, but not exclusively, within the territory of the newly established Palestinian state. And security arrangements for Israel and the Palestinian state will need to ensure against surprise attack, or use of territories as launching pads against the other. The time for incrementalism is over. Negotiations need to be undertaken with a clear time-bound approach to ensure implementation of commitments, and not recreate the conditions for failure of the Oslo process, where commitments were avoided, political balances changed, and where leadership changes resulted in radical policy shifts.

As farfetched as a two-state solution may appear today, it is the only peaceful option that preserves the unique national identity of both Israelis and Palestinians. This stark reality should be a clarion call for resolving this historic conflict once and for all.

Nevertheless, I am anything but optimistic. There is little clarity of purpose for the arduous task of moving toward peace; the political balance of power in the Middle East is further distorted; and the pressing issues of regional conflict and countering the threat of terrorism have diminished the focus on Arab-Israeli peace as a regional and international priority.

In light of existing peace agreements with Egypt and Jordan, and the security coordination with the Palestinians, Israelis feel more secure, and thus are not inclined to confront the difficult choices for a final settlement with the Palestinians. New drivers of conflict in the Arab World, from within our societies as well as with our neighbors, have understandably shifted regional priorities. A decade of a unipolar world created global imbalances in favor not of Israel, but of the Israeli right, at the cost of the Palestinians. And the inconclusive Palestinian-Israeli peace efforts were detrimental to the credibility of the nascent Palestinian authorities established as the kernel of future governing bodies of the state of Palestine.

Obstacles to a Regional Solution

Slowly, calls for realism have started to infringe on the core tenets of the Arab-Israeli peace enshrined in UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, and the parameters set by the Madrid Arab-Israeli Peace Conference in 1991. Amongst the most apparent were the assurances given by U.S. President George W. Bush to Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon in 2004 that “it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949,” thus opening the door for Israel to continue its expansionist settlement policy in the occupied territories and in effect reversing Washington’s long-standing opposition to Israeli settlements. It is not coincidental that since then the number of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories has increased exponentially.

In the past few months, talk of creative regional approaches has come to the fore with very little detail. The assumption that Arab cooperation with Israel to counter extremist elements in the Middle East, and/or the hegemonic influence of Iran, will drive the Israelis to support a viable Palestinian state, lies at the core of the “regional” approach.

Regional approaches to peace are hardly novel. The Arab Peace Initiative, announced at the Arab League summit in Beirut in 2002, is one such example offering full Arab-Israeli peace and normal relations in exchange for ending Israeli occupation of Arab territory. However, current ideas about a “regional solution” seem to be premised on absolving Israel of the hard choices involved in reaching peace with the Palestinians, and thus shifting the burden of peace altogether on the Arab states. Needless to say, the viability of such proposals is dubious at best and no doubt elicit skepticism on the part of veteran observers of the peace process. Such skepticism is justified in light of the fact that it has become increasingly apparent that the present Israeli government does not believe in a two-state solution resulting in the establishment of a viable Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. This opposition is inherently ideological, and not based on credible security considerations.

Much as I would like to see the Palestinian-Israeli conflict resolved, I expect that any effort to reach a peaceful resolution without creating a Palestinian state side by side with Israel will fail.

The alternative is that of a victor and vanquished scenario, one identity for the victor at the expense of the vanquished. That is what a one-state solution would mean, and this is not at all conducive to peaceful resolution or expressions of national identity. It will lead to the reemergence of violence, not only among nation states, but amongst the peoples themselves. This will also horrifically fuel the frustrations often taken advantage of to promote violence, intolerance, and human suffering.

Only the irrational or inhumane would have difficulty choosing the road to freedom.

Nabil Fahmy, a former foreign minister of Egypt, is the dean of the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the American University in Cairo. He served as Egypt’s ambassador to the United States from 1999–2008, and as envoy to Japan between 1997 and 1999. On Twitter: @mnabilfahmy.