Bram Fischer’s Legacy

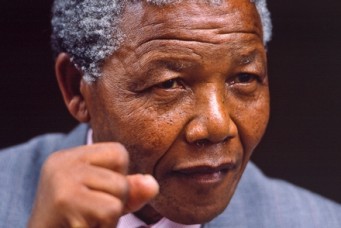

Nelson Mandela’s leadership steered South Africa to the end of apartheid rule. But the remarkable rapprochement between the races can be traced to Mandela’s friendship with an Afrikaner Nationalist who helped save the country.

Bram Fischer, Johannesburg, circa 1963. Wessel Oosthuizen/South African Sports Picture Agency.

How did South Africa avoid the bloody civil war that most people expected? After forty years of apartheid, brutal repression, and mutual fear and hostility, deeply rooted in race and ideology, the conflict seemed to be one of the most intractable in the world.

In history, cause and effect do not normally work in straight lines. There was the sudden ending of the Cold War with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The West and in particular the United States no longer needed South Africa as a strategic ally against the Soviet Union. The following year there was the wholly unexpected unilateral decision of President F. W. de Klerk to release Nelson Mandela from prison and to lift unconditionally the ban on the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). There was the pivotal juncture in 1993 after the assassination of Chris Hani, the charismatic leader of the SACP, by a white extremist, when the country stood on the brink. Mandela arrived unannounced at the studios of the South African Broadcasting Corporation, appealed to all sides to hold back, and commanded his supporters to exercise restraint. This was the moment when the mantle of national leadership and political authority if not state power changed hands. Two years later there was the famous appearance of Mandela, now president of South Africa, wearing a Springbok jersey, for decades the symbol of white Afrikaner domination, at the final of the Rugby World Cup held in Johannesburg.

When Mandela emerged from twenty-seven years in prison and extended the hand of reconciliation to the white population, and de Klerk accepted that hand, it reverberated around the globe. On paper, there was no conflict more bitter and entrenched. Much of the credit of course must go to Mandela for his unique act of forgiveness and political vision. Credit also goes to de Klerk and his minister of justice, Hendrik “Kobie” Coetsee for recognizing that apartheid and white domination could not survive the end of the Cold War—at any rate not without a bloody civil war. But the seeds of this remarkable rapprochement can be traced back thirty years earlier, to the period before Mandela was sent to Robben Island and to the extraordinary story of the relationship between Mandela, Walter Sisulu and other leaders of the ANC, and a small group of white and Indian political activists and lawyers. It is a story that changed the history of South Africa.

Afrikaners and Africanists

At a memorial service for Mandela in Westminster Abbey, Archbishop Desmond Tutu described how the world held its breath after the victory of the ANC in the 1994 election, fearing that South Africa would be overwhelmed by the racial bloodbath so many had predicted. “Instead of retribution and revenge, which everybody expected, the world saw black and white South Africans walking the path of forgiveness and reconciliation,” he said. “It was because he who spent twenty-seven years in jail came out transformed from the angry militant to the magnanimous leader who believed we each had the capacity to be great, to be magnanimous, to be forgiving, and to be generous. We cannot give up on anyone. He might not have put it like that, but basically he was saying no one is a hopeless case, with a first class ticket to hell. We all have the capacity to be saints. Nelson Mandela has shown us what we can be.”

The world knows the famous passage in Mandela’s speech from the dock at the Rivonia Trial, at which he was sentenced to life in prison. He had fought against white domination and he had fought against black domination. A democratic and free society in which all could live together in harmony and with equal opportunities was an ideal for which he had worked all his life, which he hoped to see realized and for which, if needs be, he was prepared to die. Less well known is the fact that when he began his involvement in the struggle against apartheid, he espoused a narrow Africanist approach, believing that there was no place for alliance with whites or Indians.

Mandela and the other non-white Rivonia trialists spent their long years on Robben Island engaged in intensive political discussions, in which their political views evolved. But it would be wrong to attribute, as Tutu appeared to do at Westminster Abbey, the sea change in Mandela’s thinking exclusively to the prison years. His shift to a wholehearted commitment to a multiracial approach owed a great deal to the friendships he struck up with a small group of white and Indian political activists and white lawyers as well as black African Communists at the Rivonia Trial and in the years leading up to it.

Chief among these figures was Bram Fischer QC. He is the great unsung hero of the early phase of the struggle against apartheid. He led the defense team at the Rivonia Trial and, with his brilliant conduct of the defense, saved Mandela, Sisulu, Govan Mbeki (father of Thabo, who later succeeded Mandela as the second president of a free South Africa), and the other defendants from the gallows. By proving that the ANC and Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation (known as “MK”), were separate organizations and that neither of them had yet adopted Operation Mayibuye, a controversial blueprint for full-scale guerilla warfare, he enabled the trial judge to justify passing sentences of life in prison rather than the death sentences most observers had expected.

But Fischer’s relationship with Mandela and Sisulu went far beyond that of lawyer/client. He was also acting chairman of the banned SACP and was one of Mandela’s closest political comrades. Indeed, he was a frequent visitor to what had become the MK safe house at Liliesleaf farm in the Johannesburg suburb of Rivonia from which the trial took its name. It was pure chance that he happened to be absent from the meeting of the High Command on the morning of June 11, 1963, when most of the defendants were arrested in a police raid. In fact, he had been involved in acquiring Liliesleaf as a safe house for meetings of the SACP.

Eighteen months after the Rivonia Trial, Fischer found himself back in Court C of the Pretoria Supreme Court, this time not as a QC but as a defendant standing in the same dock as his former client Mandela and charged with the same offense: conspiracy to commit sabotage. And like Mandela, he faced a possible death sentence but was sentenced to life in prison.

Road to Damascus

Fischer had come a long way from his roots. Abram Louis Fischer, known to all as Bram, was born on April 23, 1908, into one of the most prominent Afrikaner Nationalist families. His grandfather Abraham, the first and only prime minister of the Orange River Colony who later served as minister of the interior in General Jan Smuts’ South African government, referred to “stinking coolies” and “the natural tendency of natives generally to lead lives of idleness.” His father, Percy, a judge president of the Free State, had been effectively driven from practice at the bar in Bloemfontein for representing members of the Boer rebellion in 1914. Fischer himself was elected Nationalist prime minister at a student parliament, and in his speech from the dock at his trial said that he had been a Nationalist from the age of 6.

As a schoolboy at Grey College in Bloemfontein where he came top of the school in his matriculation, he persuaded the headmaster to let the boys boycott a reception for the visiting Prince of Wales .While at Grey University College where he obtained the degrees of BA and LLB, both cum laude, he became the only revolutionary Communist leader ever to have played scrum-half against the All Blacks for the Free State. In 1931 he won a Rhodes scholarship to New College, Oxford, where he obtained a diploma in law and economics.

On his return to South Africa from Oxford, he joined the bar and in due course became one of the most distinguished and sought-after QCs in South Africa, specializing in commercial and mining law. Had he wished, he could have attained, by reason of his family connections and his talents, the highest political or judicial office in apartheid South Africa. He was tipped as a future prime minister or chief justice. Instead, he turned his back on personal ambition in favor of pursuing the ideal of a fair and just multiracial democracy.

As a young man, Fischer had a Road to Damascus experience. He was distressed to feel revulsion at shaking hands with a black man. He recalled that, as a child growing up on a farm, his two best friends had been black and he realized that he had become brainwashed with the irrational culture of racial prejudice. Years later in his speech from the dock in which he explained why he had become a Communist, he traced it back to this epiphany. At that time the Communist Party was the only party that was open to all races and advocated an extension of the franchise. While at Oxford Fischer travelled to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1932 and, although it is not clear exactly when he joined the party, by the time of the 1946 miners’ strike, he was a member of the Johannesburg district committee. When the other members of the committee were arrested for inciting the strike while he was out of town, he insisted on being charged alongside his comrades. When the party was banned in the 1950s he remained a member of the successor SACP, in due course becoming acting chairman.

Together with his wife, Molly, who also came from a patrician Afrikaner family (she was the niece of the wife of General Smuts) and also joined the Communist Party, Fischer dedicated his life to working for the overthrow of apartheid. This manifested itself in his personal, professional, and political life. He was widely regarded even by many who did not share his political opinions as a man of complete integrity. In many areas of his life he lived the change he wanted for his people and his country. His house on Beaumont Street in Johannesburg became a home to multiracial social and political gatherings, including mixed-race bathing in his swimming pool, which were unique at the time; Mandela and Sisulu were frequent visitors. Fischer informally adopted a young orphaned African girl who shared a bedroom with his younger daughter, Ilse. It is hard to convey how exceptional this was. In the desert of racial separation entrenched and developed by apartheid, this house was an oasis of genuine racial equality, friendship, and respect.

Throughout the 1950s and up to the Rivonia Trial in 1963, Fischer straddled the worlds of the law and anti-apartheid politics, acting for both Mandela and Sisulu in a series of political cases that he conducted alongside his commercial practice. At the beginning of his political career, Mandela was not at all in sympathy with Fischer’s position. When he first assumed a leadership role in 1949 in the ANC Youth League with Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, with whom he founded the first black attorney’s firm in South Africa, he was, in his own words, “fiercely nationalistic in our approach and anti-White, anti-Indian, and anti-Communist.” In his speech at the funeral of Elias Motsoaledi, one of the Rivonia defendants who died on the day of Mandela’s presidential inauguration in 1994, Mandela said: “Comrade Motsoaledi was a member of the Communist Party of SA as it was then known. We had many clashes in which he criticized us and at times attacked us viciously for what he considered very conservative and reactionary views. But in that debate we learned a great deal, because when you debate issues of that nature, if you approach that debate with seriousness and earnest at the end of the debate you find yourself closer to your rivals than you were before that debate.”

Gradually through the 1950s, Mandela softened his attitude both to the Communist Party and to alliances with white and Indian activists. As well as black Communists such as Motsoaledi and Moses Kotane, Fischer played a key role in this process. Mandela told Fischer’s biographer Stephen Clingman: “Even when we were attacking the Communist Party I used to say that Bram is really exceptional. He was not really a Communist. He was in that party because there was no other party that men like him could join.”

That is an assessment with which Fischer probably would not have concurred. When his close friend and one of his junior counsel at the Rivonia Trial George Bizos made a similar comment to an American academic observing the trial who expressed surprise that such a brilliant and charming man should be a Communist, Fischer, in a rare outburst of anger, reprimanded him: “George, don’t you ever apologize to anyone for my political beliefs again.” He was a party loyalist and made it clear in his speech from the dock that he fully believed in what he called scientific Marxism. How did a man of his brilliance and integrity maintain that loyalty in the face of the mounting evidence of Stalin’s crimes? A possible clue is provided by Bob Hepple in his book, Young Man with a Red Tie: A Memoir of Mandela and the Failed Revolution, 1960–1963. He was asked by Fischer if there were any writings that refuted the revelations of Stalin’s crimes that he could show his daughters. When Hepple said the evidence against Stalin was irrefutable, Fischer’s response was: “Well we now know what to avoid when we establish Communism here.”

Mandela assessed Fischer’s attitude not from what he said but from the way he treated his black workers and the risk he took in adopting a black child. He told Clingman: “The woman who worked for him regarded Bram as a brother, and she would be involved in his parties not as a waiter but as a colleague, as a comrade and then you saw what type of man Bram was.” Sisulu described Fischer as a very kind man. He remembered him getting up when his son Paul, who suffered from cystic fibrosis, coughed in the night and was touched by the sound of him running to be with Paul. Sisulu said it was as if Fischer’s children were his own. “When Paul finally died, it was like my own child had died,” he said.

By the time Kotane told Chief Albert Luthuli, the then-president general of the ANC, that the SACP was about to announce its underground existence in 1960, Luthuli queried whether the party still included people like Fischer because only then could he trust it. This reflected the degree to which friendships and alliances had been forged across the racial divide between leaders of the ANC and the SACP.

Luthuli, Slovo, and Bernstein were among the 156 leaders of the ANC and the other groups fighting apartheid, including the South African Indian Congress (SAIC), the South African Coloured People’s Congress, the SACP, and the white Congress of Democrats, who had been arrested and tried at the so-called Treason Trial. Slovo, a barrister, was a Jewish Communist advocate who later joined the High Command of MK and in 1963 argued (against Fischer and Sisulu) for the adoption of guerrilla warfare. Bernstein, also a Jewish Communist and married to Hilda Watt, who in 1942 became the only Communist ever elected to public office under apartheid when she won a seat on the Johannesburg city council, was an architect.

In 1954, sifting through literally thousands of written responses, mostly from Africans, Bernstein had been largely responsible for drafting the Freedom Charter which was adopted at the 1955 Congress of the People in Kliptown, and ratified by the ANC the following year. He worked closely with Mandela, Sisulu, and Tambo in the Congress Alliance which organized the Congress. The Freedom Charter, which underpinned the ANC for the next forty years and later found expression in the post-apartheid constitution of South Africa, proclaimed the right of the people to a free and multiracial democracy: “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white.”

Black, White, and Indian

Second only to the Rivonia Trial, the Treason Trial was the most important political trial of the apartheid era. It lasted from 1956 to 1961 and ended with the dismissal of all charges. Its unintended but perhaps most important lasting contribution to the peaceful end of apartheid was the opportunity it created for the black, white, and Indian leaders of the opponents of the regime to discuss political as well a legal tactics, strategy and policy and in the process get to know each other. It was a spectacular own goal on the part of the Nationalist regime. Most of the defendants had been banned from taking part in any political or public meetings; the daily bus journeys between Johannesburg and the court in Pretoria provided them with a unique forum to develop personal and political relationships. Luthuli wrote that if there was one thing that helped push the movement along non-racial lines, away from narrow, separative racialism, it was the Treason Trial, which showed the depth of sincerity and devotion to a noble cause on the white side of the color line. He singled out for praise “the brilliant team of legal men who defended us so magnificently for so little financial reward.”

In particular Fischer’s role was critical. Such was his standing at the Johannesburg Bar (despite his well-known political views he was the longest-serving member of its Bar Council and ultimately became its chairman) that he was able to persuade the non-political leaders of the bar to act for the defendants. As second QC under Issie Maisels QC, he contributed to the successful outcome with his patient and skillful cross examination; it persuaded the judges, by whom he was held in high esteem, that the defendants were committed to the ideal of a multiracial democracy to be achieved by non-violent means, albeit including civil disobedience.

Unlike most of their other lawyers, Fischer was regarded by many of the defendants, including Mandela and Sisulu, as a friend and comrade as well as an advocate. He would invite them to dinner at Beaumont Street and undertook the task of helping solve many personal and family problems during the long years when they and their families endured great financial privations. He had already acted for Mandela, Sisulu, and eighteen other Congress leaders in 1952 when they were charged under the Suppression of Communism Act for their activities in the Defiance Campaign. In 1954, he had arranged for another leading QC to act pro bono for Mandela in his successful resistance of an attempt to have him struck off the roll of attorneys because of his involvement in that campaign.

After the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 and the introduction of repressive emergency legislation that outlawed the ANC and allowed first 90- and then 180-day detention without trial, Mandela persuaded the ANC to adopt a policy of selective and nonlethal sabotage. He went underground and MK was formed, with him as its leader and its High Command drawn from the ANC and the SACP. This extended his close collaboration with white and Indian activists. Among those who drove Mandela to clandestine meetings (or rather he drove them, disguised as a chauffeur so as not to attract attention) were Bob Hepple and Ahmed Kathrada. Hepple was a young Jewish advocate who was co-opted by Fischer onto the Central Committee of the SACP. Kathrada was a leading young member of the SAIC, who a decade before as a leader of the Young Communist League had clashed with Mandela over Mandela’s opposition to a strike organized jointly by the ANC and the Transvaal Indian Congress. He had challenged him to a public debate that he boasted he would win, for which he was roundly rebuked and about which they later teased each other on Robben Island.

In 1962, Mandela was arrested while “chauffeuring” another white comrade, a film director called Cecil Williams, from Durban to Johannesburg, and was sentenced to five years in prison for inciting a strike and leaving the country without a passport. He decided to wear tribal dress and to take no formal part in the trial, declaring that he was “a black man in a white man’s court.” However, in place of Slovo, now under a banning order, he asked Hepple to give him informal legal advice and, before being led off to prison, warmly embraced him. Their next meeting would be at an event at Buckingham Palace in 1996, and Mandela again embraced Hepple. Hepple had been tortured and then released from prison during the Rivonia Trial in exchange for agreeing to give evidence for the prosecution. Fischer had organized his escape from South Africa to avoid him giving evidence. He was living in exile in England where he had recently become Master of Clare College, Cambridge. As Mandela lined up to be presented to the Queen, he spotted Hepple: “Bob, is that you?”

There were by now very close ties between the ANC, the SACP, and the High Command of MK, which included Fischer, Slovo, and Bernstein, as well as Mandela, Sisulu, and Mbeki. When the police raided the Liliesleaf safe house on June 11, 1963, they interrupted a debate on whether Operation Mayibuye should be adopted. Those arrested included Sisulu, Mbeki, Hepple, and Bernstein, as well as Kathrada and Denis Goldberg, who was responsible for buying equipment for the sabotage campaign.

At the Rivonia Trial, Fischer led the most brilliant legal team ever assembled in South Africa—Vernon Berrangé QC, George Bizos, Arthur Chaskalson, and attorney Joel Joffe. Although with the exception of Berrangé the other lawyers were not political activists, they were all committed opponents of apartheid. There was a real sense of camaraderie between the defendants and their lawyers, who were subjected to intimidation and harassment by the regime. In heading the defense, Fischer took the huge risk of being identified by prosecution witnesses since he had himself been a frequent participant at meetings at Liliesleaf.

It was not the only risk Fischer took. When Kathrada had been detained after Sharpeville, Fischer smuggled a radio into prison for him. During the Rivonia Trial, he and Molly smuggled letters in and out of prison between Kathrada and his white girlfriend, Sylvia Neame. Once in the dead of night, he broke into the garage of another safe house in Mountainview where, before his arrest, Goldberg had parked a van which was registered to the Rivonia safe house and freewheeled it down a hill so that the owners of the safe house would not be compromised if the van was found there. He then tried to arrange for Goldberg to escape from prison and aided Hepple’s flight from South Africa.

George Bizos had come to South Africa in the Second World War as a 13-year-old refugee after helping his father, the mayor of a Greek village, rescue seven New Zealand soldiers from the Germans. As a young advocate, he was often instructed in political cases by Mandela, with whom he would share sandwiches in his car—the law prevented them from lunching together in a restaurant. Before the trial began, he brought Greek delicacies to lift everyone’s spirits in the drab prison cell where they met to discuss tactics. It was Bizos who persuaded a skeptical Fischer to expose Sisulu, who had only a few years’ schooling, to the cross-examination of Percy Yutar, the only prosecutor in South Africa with a PhD. Over six days Sisulu wiped the floor with Yutar. Bizos remained one of Mandela’s closest confidants throughout the prison, transition, and post-apartheid years.

Joffe had decided to emigrate to Australia to avoid bringing his children up under apartheid but deferred his departure to take on the defense. On top of his key role as sole attorney in the case, he raised the funds for the defense and acted as an informal welfare officer for the families of the defendants. Berrangé, a former Communist and the most feared cross-examiner at the bar, effectively sacrificed any chance of continuing to practice in South Africa by taking on the case.

Denis Kuny had previously risked everything by agreeing to let Mandela chauffeur him to Port Elisabeth when he was on the run. According to Kuny, Chaskalson had taken a similar risk by lending him his car for the same purpose. Kuny acted for James Kantor, an apolitical solicitor who lived a playboy lifestyle and was arrested by the Special Branch out of pique because his brother-in-law Harold Wolpe, a leading SACP figure, had escaped from the Marshall Square police station. Such was Mandela’s admiration for Chaskalson, who later gave up a lucrative commercial practice to establish the Legal Resources Centre to fight test cases against apartheid laws, that when he became president he appointed him first to the Constitutional Court and then as chief justice. When he knew he faced a life behind bars Bram Fischer gave Chaskalson his advocate’s gown and his desk, which Chaskalson took with him to the Constitutional Court.

As for the defendants themselves, there were eleven of them—six black, one Indian, and four white. By the time they stood to hear the judge pass sentence there were eight, of whom one was white. Hepple had fled the country, the charges against Kantor were thrown out at the end of the prosecution case, and Bernstein was acquitted. The trial lasted eight months and by the end the bonds of comradeship that had been forged between them under the threat of the gallows lasted a lifetime. In 2014, Goldberg revisited Court C in the Pretoria Supreme Court and sat in the dock in which he had heard Mandela end his peroration by declaring that he was prepared to die for the ideal of a multiracial democracy. “He wasn’t just saying ‘hang me,’” he explained. “He was telling the judge, ‘Hang Walter, hang Govan, hang Denis, hang all of us.’ It created a bond that can only be broken by death. I’m sorry, but it’s stronger than the bond between husband and wife.”

Before, during, and after the trial there were acts of great bravery and solidarity. Kantor, who had been offered his freedom if he betrayed the others, warned Hepple and Bernstein not to pass on any secrets to him lest he reveal them under torture. Goldberg, at the first meeting of the defendants, when they were released from 90-day detention and charged with sabotage, which carried the death penalty, offered to take all the blame if it would save the others. Kathrada, who was advised that he had a very good chance of overturning his conviction and/or life sentence, declined to appeal as a matter of solidarity and spent twenty-six years in prison rather than break ranks.

Tragedy, Compounded

The day after the Rivonia Trial ended, Fischer’s wife, Molly, drowned in a freak car accident, a fact of which he made no mention when visiting his clients/comrades on Robben Island to discuss whether they should appeal, so as not to burden them with his personal tragedy. It was typical of his ascetic and self-effacing character and his consideration for others. When a prison guard informed Mandela about Molly’s death, he wrote Fischer a letter of condolence that the authorities refused to deliver.

When Fischer was himself arrested a few weeks later for membership of the outlawed SACP, he got bail to argue a case in the Privy Council in London. He refused entreaties to estreat bail and remain in London because “I gave my word” and because he believed it vital for leaders, particularly white leaders, of the struggle against apartheid to make a stand inside the country.

However, Fischer then made a further life-changing personal sacrifice. In the middle of his trial, at which he faced a maximum of five years in prison, he decided that he could best continue his fight against apartheid by going underground, thereby courting a life sentence and possibly even a death sentence when in due course, as was inevitable, he was captured. In his prophetic letter to the court he said that any sentence passed on his co-defendants would be punishing them “for holding the ideas today that will be universally accepted tomorrow.” He explained that he “could no longer serve justice in the way I have attempted to do during the past thirty years. I can do it only in the way I have now chosen.”

By surviving for nine months underground in heavy disguise (the “Red Pimpernel” to the “Black Pimpernel” as Mandela was called in his period underground) at a time when the national leadership structure of both the ANC and the SACP had been smashed by the Rivonia and other raids, Fischer raised the defiant banner of resistance and made a symbolic stand to show the world that at least one Afrikaner stood shoulder to shoulder with the non-white imprisoned leaders of South Africa’s freedom movement. It boosted the morale of Mandela and the other prisoners on Robben Island. When Bizos made a prison visit, Mandela’s first inquiry was to find out how Fischer, whose nom de guerre was Shorty, was faring. This he did by holding his hand at chest height with his thumb outstretched turning it questioningly up and down. When he saw Bizos’ thumb pointing firmly up in the air, a broad smile crossed his face.

When Fischer was finally captured, he was charged with sabotage and the prosecution called for the death sentence. He refused to testify in his own defense because his loyalty to his comrades would not permit him to implicate others and his respect for the rule of law would not permit him to lie on oath. Instead, like Mandela before him, he chose to read a statement from the dock to explain the choices he had made. Also like Mandela, he was a passionate believer in the rule of law but, as he said in this historic speech from the same dock where Mandela had made his famous speech two years earlier, “When the laws themselves become immoral and require the citizen to take part in an organized system of oppression—if only by his silence and apathy—then I believe that a higher duty arises. This compels one to refuse to recognize such laws.” In that speech, which remains one of the most inspiring political speeches of the twentieth century, Fischer explained why he had felt compelled to join first the Communist Party and then the underground struggle against apartheid:

All the conduct with which I have been charged has been directed towards maintaining contact and understanding between the races of this country. If one day it may help to establish a bridge across which white leaders and the real leaders of the non-white can meet to settle the destinies of all of us by negotiation, and not by force of arms, I shall be able to bear with fortitude any sentence which this court may impose on me. It will be a fortitude, my Lord, strengthened by this knowledge, at least, that for the past twenty-five years I have taken no part, not even by passive acceptance, in that hideous system of discrimination which we have erected in this country, and which has become a byword in the civilized world.

Fischer paid a heavy price for his principled and visionary refusal to acquiesce in what he saw as the evil and unjust system of apartheid. In 1966, at the age of 58, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. His decision to go underground, followed by his life sentence, meant that he was unable to continue looking after his son Paul, whom he and Molly had nursed with devotion all his life. When Paul died in 1971 at the age of 23, Fischer was not permitted to attend the funeral.

The prison authorities in Pretoria Local Prison, who viewed Fischer as a traitor to his Afrikaner people, singled him out for especially harsh and cruel treatment. He was made to clean latrines with a toothbrush and was shown off in his cell, like a prize exhibit in a museum, to friends of the warden after drunken dinner parties. When he became ill with cancer and suffered a painful breach of the femur, he was treated with callous indifference and it was left to Denis Goldberg, his comrade, former client and fellow prisoner, to nurse him as best he could. (Among the Rivonia defendants, only Goldberg was not allowed to serve his life sentence on Robben Island with his comrades; the hand of apartheid reached even into prison). Even though it was obvious by 1974 that Fischer was terminally ill and had only a few months left to live, the state refused to free him.

Fischer died of cancer on May 8, 1975, at the home of his brother, Paul, which had officially been designated part of the prison estate so that his visitors could be restricted. Shortly after the funeral the prison authorities confiscated his ashes lest his grave should act as a shrine for his many admirers. They were never recovered.

Alone of the Rivonia defendants and their lawyers, Fischer did not live to see the Promised Land of a free and democratic South Africa. But his influence on the thinking of Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and other leaders of the ANC as well as on other members of the legal team manifested itself in the critical negotiations after Mandela’s release from prison and in the creation of the new South Africa.

Nelson Mandela, his former client, who had started out nearly fifty years earlier with a narrow Africanist approach, became the first president elected by a universal franchise and appointed F. W. de Klerk, an Afrikaner Nationalist, as his vice president. Mandela said that in any history written of South Africa two Afrikaner names will be always remembered: Beyers Naude, the anti-apartheid minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, and Bram Fischer. Delivering the Legal Resources Centre’s inaugural Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture in 1995, President Mandela said that as he stood at the voting booth in the first free elections the previous year, one of those next to him, alongside Oliver Tambo, Chris Hani and Albert Luthuli, was Bram Fischer.

“As Comrades, As Brothers”

Fischer occupies a unique place in the history of the struggle against apartheid and the fight to achieve a peaceful transition to a multiracial democracy in South Africa. By his conduct of the defence at the Rivonia Trial, he played the key role in saving Mandela and the senior leadership of the ANC from the gallows. By his willingness to sacrifice his career, his family life and his liberty in the cause of securing freedom for the majority black population, he helped to influence Mandela to abandon a narrow Africanist approach and sowed the seeds of Mandela’s magnanimous extension of the hand of friendship and reconciliation to the white population when he was released from Robben Island. By his personal example he showed that there were white South Africans, and in particular Afrikaners, who were prepared to put the interests of freedom and justice for all above their own personal interest. He succeeded in creating the bridge between his Afrikaner people and the legitimate leaders of the black population, which in 1994 enabled them to settle their differences without a bloodbath, as he had hoped in his speech from the dock.

Mandela said in his Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture:

As an Afrikaner whose conscience forced him to reject his own heritage and be ostracized by his own people, he showed a level of courage and sacrifice that was in a class by itself. No matter what I suffered in my pursuit of freedom, I always took strength from the fact that I was fighting with and for my own people. Bram was a free man who fought against his own people to ensure the freedom of others.

Referring to Fischer’s elite Afrikaner heritage and early espousal of Afrikaner Nationalism, Mandela added:

With that background he could not but have become an Afrikaner Nationalist, as we became African nationalists thirty years later as a result of our oppression by whites. Both of us changed. Both of us rejected the notion that our political rights were to be determined by the color of our skins. We embraced each other as comrades, as brothers, to fight for freedom for all in South Africa, to put an end to racism and exploitation.

Sir Nicholas Stadlen is a former English High Court Judge (2007–13) and distinguished Queen’s Counsel. From 2006 to 2007, he published the Brief Encounters series of podcast interviews in the Guardian with Gerry Adams, Hanan Ashrawi, Shimon Peres, Desmond Tutu, and F. W. de Klerk. He has conducted extensive interviews with the surviving defendants and lawyers who took part in the Rivonia Trial. In March, he chaired a colloquium at the University of the Witwatersrand on the life of Nelson Mandela’s defense counsel Bram Fischer. He will be a Visiting Fellow at St. Antony’s College Oxford in 2015-16.