Exposing Inequality, Accelerating Innovation: COVID-19 and the Digital Economy

COVID-19 has highlighted the great promise borne by the digital economy, as well as the challenges standing in the way of reaping its full potential.

The COVID-19 global pandemic has demonstrated the prominence of the digital economy and its ability to quickly digitize and digitalize practices such as education and governance.

The flip side, however, is that we now understand there to be a significant digital divide between those who are either without internet access or unskilled in the use of modern technology, and those who could easily work and learn from home.

Working from home-and the acronym WFH it produced on social media-has been an enormous advantage for economies in crisis, when jobs are in peril or when schools shut down and human productivity appears to be lost.

The Access to Knowledge for Development Center at the American University in Cairo (AUC) tackled the effects of the pandemic on the digital economy and the outlook for the future, in a webinar as part of a series for their tenth annual workshop.

Titled “The Digital Economy Post COVID-19: Global Outlook and Local Contexts”, the webinar was moderated by Nagla Rizk, founder of the Access to Knowledge for Development Center and a Professor of Economics at AUC.

She opened the discussion by referencing the “common narrative” surrounding the digital economy, which is that it can be harnessed for great growth and development but also serves to widen the digital divide. Rizk then set the tone of the discussion by asking one central question: how, if at all, has COVID-19 changed the common narrative?

Effect of COVID-19 on the Digital Economy

In today’s world, it is not at all uncommon to hear the clichéd phrase that the world is changing at an unprecedented rate, and for good reason; technological innovation is driving such rapid change.

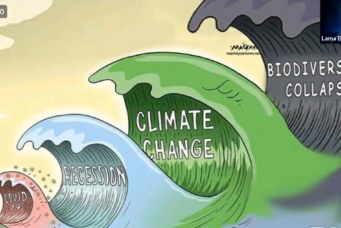

The first three industrial revolutions respectively brought forth steam engines and spinning looms; the electrification of industry; and digitization with the advent of circuit boards, computers and the internet. The world is now undergoing what some claim to be a fourth industrial revolution, characterized by increasing digitization and digitalization, the combining of different technologies, and technological innovation at an exponential rate. We are entering what some refer to as the second half of the chessboard–incomprehensible exponential growth. While the digital economy bears much promise for innovation and creativity, access to technology is highly unequal, thus creating a digital divide and exacerbating pre-existing inequalities.

Fabian Stephany, a researcher in Computational Social Science at the Oxford Internet Institute and one of the webinar panelists, began by questioning the very positive narrative of the internet as the bastion of free access and equality, stating that demand for online work in Africa is “only roughly 3% of the global demand of online work”, making clear that high inequality persists. On the effect of the pandemic, Stephany observed a fragmentation of work and that “digitalization will be promoted by COVID-19”. The question he raises, however, is whether such a process will move at the same speed for all parts of society. It appears that there is a lot of catching up to do in that regard.

According to panelist Monica Kerrets-Makau, the Academic Director at Thunderbird’s Center for Excellence for Africa and consultant to the World Bank, there are factors which must be taken into account: infrastructure, access, and costs. Kerrets-Makau observes a shift in how technological companies are altering their models to increase access in Africa, creating low-cost pay-every-day models. However, despite some progress, the question of internet penetration in Africa is still one which needs to be answered, as penetration rates are much lower compared to Europe.

When it comes to the nature of work, Kerrets-Makau says that the corporate sector in Africa has adapted to the pandemic, small and medium enterprises are changing how they do work, and the mobile banking and money transfer sector is experiencing a big shift, especially in Eastern Africa. Additionally, costs of digital transactions in Kenya have been eliminated for transfers up to one thousand shillings. However, she warns that people need to be watchful of predatory lending practices, and carefully consider the interest rates and terms they’re agreeing to.

When it comes to education, Kenya opened in-person teaching to three grades, with other grades and private schools continuing to teach online. Kerrets-Makau notes that the pandemic highlighted the economic divide between those who can afford to go online and others, including public schools, which cannot afford to go online due to problems in infrastructure, access, and costs, highlighting the digital divide which occurs not only between different countries, but within them as well.

Post-COVID Challenges and Solutions

It is clear that the pandemic had an accelerating effect on the nature of the digital economy. While it didn’t necessarily change the shape of the digital economy, it did force a development of phenomena that were slowly maturing, such as online learning, or inequality of access to technology. As Rizk neatly put it, it calls upon us to address scenarios that we anticipated to take place in the future.

COVID-19 is the present and its effects will be felt long into the future, which is for us to shape as a global society. Returning to the status quo before the pandemic, or keeping the present structures in place , is impossible. What lies ahead are a set of long-standing questions which have either been amplified or had their answers reevaluated by COVID-19. The nature of work as we know it is changing, and so is the nature of education, governance, and communication. Accordingly, several challenges lie ahead.

Continuing with her focus on Africa, Kerrets-Makau identifies data as a significant challenge in the continent. She says that governments are hoarding data, and citizens, who are mistrustful of regional governments, are scared of data misuse, especially when it comes to elections. This must be addressed by bringing everybody to the table and finding answers to questions on data ownership and usage.

Another top challenge is facilitating access and affordability of digital technology. She makes the point that good infrastructure alone has little use if access and affordability of the technologies it provides are restricted by heavy taxation. She suggests making duty exemptions to devices crucial for facilitating access to the internet, such as phones and computers.

Finally, she warns that governments have to be less hasty in bringing out the “regulatory stick” when addressing innovation, noting that “the aim of regulation is to eliminate regulation.” She calls on the government to coordinate between the private and the public sectors, thinking differently across different institutions and facilitating cross-cutting cooperation across different sectors.

Stephany encourages cross-cutting cooperation, adding that despite the internet’s huge potential, activities are still clustered in certain circles and geographical areas. This goes back to the three concerns of infrastructure, access, and costs raised by Kerrets-Makau. Furthermore, AI promises to play a big role in the digital economy, but there are still questions of racial bias in the development of AI systems. This is a problem which stems from the lack of diversity among AI programmers, perpetuating their own biases in the programming; and from a lack of input by those who have limited access to such technology due to the digital divide.

To Stephany, education is key–“education, education, education”. And here he isn’t only referring to traditional education, but also to digital literacy and reskilling. He stresses that the more digital technology progresses, the more automation progresses and expands into our lives and work. In this regard, Stephany claims that we must think of automation of tasks rather than automation of jobs, which may lead to some unemployment but will also increase demand for more skilled labor. As such, there must be intensive efforts to reskill and upskill workers, looking for valuable pre-existing skills and complementing them with critical new skills related to digital technology. Stephany gives the example of someone who has a background in statistics combining this with knowledge of machine learning to become a data scientist, for example.

Stephany dubs this phenomenon “agile cross-skilling” where people remove and add new things to their skillset. He emphasizes that cross-skilling mustn’t be a one size fits all approach, and that it must be tailored to the needs of each individual.

As Keretts-Makau puts it, “COVID-19 is a free of charge consultant”. Indeed, it has shown us the flaws in our economic systems and the challenges that lie ahead, the extent of inequality both between and within states, not to mention the real effects of maintaining such a digital divide; and the huge potential of the digital economy as a platform of creativity, innovation, and empowerment. Moreover, it has shown us that history is not linear; as we enter the second half of the chessboard and experience an exponential proliferation of digital technology in our everyday lives. Under the umbrella of the fourth industrial revolution, we begin to understand that our response as governments, thinkers, and policy makers must be its equal in robustness.

Omar Auf is deputy senior editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. He has previously worked and published in independent media organization Mada Masr and as an assistant editor at the Cairo Review.

Auf holds a Master of Global Affairs degree with a regional and international security concentration from the American University in Cairo, and a Bachelor of Arts in economics from Sciences Po Paris.

Read More