The Changing Middle East Regional Order

A history of the Arab state system starting from the second half of the twentieth century to the present

Middle Eastern leaders meet during the Baghdad summit in Iraq, August 28, 2021. Iraqi Prime Minister Media Office/Reuters

During the second half of the 20th century, there was at least order in the Arab World, even if precarious. Represented by the League of Arab States, the practice of Arab summitry provided some semblance of regional order. However, this precarious order broke down in stages, firstly as a result of Egypt’s separate peace with Israel in 1979 and later due to Iraq’s invasion of a fellow Arab state, Kuwait, in 1990. Meanwhile, the positions of non-Arab players shifted. After 1979, Iran turned away from the West to focus on building influence in the Arab-Muslim world. Two decades later, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has also recalibrated Turkey’s foreign policy, balancing a continued interest in Europe with rebuilding influence in the former Ottoman Arab World.

To this day, the region continues to undergo dynamic changes as new regional alignments and divisions ebb and flow, but all without yet arriving at an overarching political, economic or security architecture that could build on common interests, manage areas of difference, and work to avoid direct or proxy conflict.

There is an increasing need for such an effective regional order. Already beset by high levels of conflict, inequality, and unemployment, the region is facing a future further challenged by climate change, water scarcity, and other unpredictable systemic challenges, as vividly illustrated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. There is a budding awareness of the need to turn away from decades of geopolitical contestation and focus on the common systemic issues faced by the societies of this region in a challenging century.

But a history of division and tension runs deep, and the goal of regional order still seems dangerously beyond the horizon.

The Arab Regional Order Leading Up To 2020

In 1987, Egypt had been readmitted into the Arab League after its membership was suspended for signing the 1979 peace treaty with Israel. Cooperation between Egypt and Saudi Arabia provided a partnered leadership between the most populous and wealthiest Arab states. Saddam Hussein’s regime, which had challenged the Arab order in 1990 by invading Kuwait, was removed by the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq—an invasion which would generate its own set of major regional threats and challenges. Arab summits resumed with a sense of complacency and assurance that an old familiar order had been restored. But that order was facing serious challenges from within and without.

From without, external players began intruding into the Arab region in new and unprecedented ways. During the Cold War, global powers—namely the United States and the Soviet Union—built enormous influence in the Middle East by choosing and aligning client states along the East-West axis. But it is noteworthy that the global powers competed largely by proxy, avoiding large-scale direct military interventions of their own for fear of escalating direct conflict with the rival superpower. The collapse of the Soviet Union removed that constraint. When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, the United States went ahead with a full-scale military deployment in the Middle East without any concern for a backlash from Russia. And when Al-Qaeda attacked the United States on September 11, 2001, the United States, again, felt no restraint in sending forces to topple the Taliban regime in Kabul and the Saddam regime in Baghdad. The United States was not the only global power to take up direct military intervention. Russia would recover from the collapse of the Soviet Union and follow suit in 2015 with a military intervention in support of the Bashar Al-Assad regime in Syria, although it was not the only actor in this multi-party-led external intervention. From without, regional powers were increasing their presence as well.

Iran

Since the emergence of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Iran signaled its interest in becoming a direct and powerful player in the Arab World. Throughout the 1980s, Iran had remained fairly contained by Saddam’s power and by an Arab state system that held firm. Iran’s main breakthrough, however, was in Lebanon. State collapse from the 1975 civil war created conditions that allowed Iran to build up Hezbollah as a powerful Iranian proxy throughout the 1980s and beyond.

Iran’s second chance came in 2003, when the United States toppled an Iraqi regime that had kept it largely in check, enabling Iran to emerge as the dominant power in Iraq. Iran’s third breakthrough came as Al-Assad’s regime in Syria risked collapse at the hands of a popular uprising that started in 2011. Iran rushed to the aid of its ally, sending in Iranian, Lebanese, Iraqi, and other militia and military forces under the leadership of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, solidifying its influence in Syria. Its most recent breakthrough came in 2014 in Yemen, where an alliance between the Houthis and former president Ali Abdallah Saleh toppled the transitional government in Sanaa and unleashed a civil war that continues to this day. The Houthis welcomed Iranian support, and Iran has now added another Arab capital to the list of capitals in which it has a strong and seemingly long-lasting presence and influence, including Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad.

Turkey

After almost a century of shunning the Arab-Islamic world and looking westward, Turkey has also sought to reclaim its influence in the Arab World under Erdoğan’s leadership. In 2010, this appeared to be a fairly benign and constructive interest: Turkey was presenting a convincing model of political democratization and economic development; a balance of traditional values and vigorous modernization projects; and the potential for integration with the West via the European Union. Erdoğan promoted a “no problems with neighbors” foreign policy, focused on improving regional cooperation and integration based on common economic interests and win-win solutions, and exported an increasing number of consumer goods and TV soap operas to the Arab World. This changed dramatically after the Arab uprisings of 2011.

Erdoğan saw an opportunity to regain a powerful role for Ankara in the Arab World by backing the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots, who seemed on track to become the ruling party in several Arab countries including Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen, and potentially major players in Morocco, Jordan, and Kuwait. However, his gamble did not pay off, as the Muslim Brotherhood was removed from power in Egypt and failed to make the promised gains in other Arab countries. A chastened but frustrated Erdoğan scaled back his ambitions but compensated with a direct military intervention in Syria and Iraq and a strong proxy presence in Libya.

States of the Arab uprisings

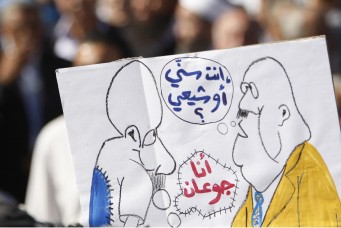

However, the main challenge to the Arab order came from within, in the form of the 2011 Arab uprisings. These uprisings shook the Arab state system to its core, as people finally expressed decades of pent-up frustration over unequal socioeconomic conditions and repressive political institutions. The effect of these events at the regional level was significant. First, they led to full or partial state failure in a number of key Arab states, including Libya, Yemen, and Syria. These collapses created vacuums that would be filled by a number of state actors such as Iran, Turkey, Russia, and the United States, as well as non-state actors such as Hezbollah, the Houthi forces, the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces, ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and affiliated jihadist groups. At the regional level, the uprisings and the potential rise of the Muslim Brotherhood—as well as the rift with Qatar which appeared to be encouraging both—also cemented the Arab Quartet, a regional alliance between Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain.

All of these events, especially those following the 2011 Arab Spring, helped form the current relationships and alignments within the Middle East. The Arab Quartet acted as the new center of the Arab World, commanding the bulk of its economic resources. But Iran has successfully become the dominant power in the “center” of the Arab World with its dominance in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. It has also gained a long-term foothold on the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen. Turkey’s influence has ended up well below its ambitions, with only pockets of influence, mainly in Syria and Libya.

Israel

The breakthrough country, since 2020, has been Israel. In that year, the Abraham Accords, signed between Israel, Bahrain, and the UAE, catapulted Israel into key partnerships with wealthy and influential Arab monarchies. It has also begun normalizing relations with Morocco, the major player on the western reaches of the Arab World. This Israeli breakthrough, particularly in the Gulf, is likely to have important impacts on economic development, technology, trade, and investment, but is also transforming the security relationship between Israel and the Arab Gulf states, as both share an existential fear of Iran. The accords also mark a definitive shift away from years of Arab policy on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, which, since the Arab peace initiative of 2002, has offered normalization only in exchange for a two-state solution for the Palestinians. After decades of being a player excluded from the region, Israel—like the non-Arab Middle Eastern states of Iran and Turkey, but in very different ways—is now also a player inside the Arab World.

The 2022 Regional Order

There is no overarching Middle East order today. We can speak perhaps of two (or rather, two-and-a-half) sub-orders. The first is the centrist Arab order led by the aforementioned Arab Quartet. It promotes stability and economic development, believes in top-down governance, and is, therefore, antithetical to democracy. It is hostile to Iran and radical Islamist groups and is aligned generally with the United States, although it enjoys growing economic relations with China and is open to relations with Russia.

The second sub-order is one that is dominated by Iran and includes the Levantine countries and a big part of Yemen. It is debatable whether this can be considered a sub-order of states, as most of the states in this Iranian sphere of influence are either fully or partially failed, or are in extremely precarious situations. Iran’s agenda in these states is partly aggressive defense against the perceived threats from the United States, Israel, and radical jihadist groups like ISIS. Iran has enjoyed a fair measure of backing from both Russia and China, who share part of its ambition to limit U.S. influence. But it is also a forward-leaning ideological agenda representing both the Islamic Republic’s own revolutionary ambitions to transform and lead the wider Muslim world, and also a revived Iranian appetite to reclaim its prominence in the heart of the Middle East—a role that it has enjoyed on and off in past centuries and millennia. The remaining “half order” is the small Turkish sphere of influence scattered between Syria, Libya, and other parts of the Middle East, although this hardly rivals the other two.

Internationally, the great powers cast long shadows across this Middle East. The United States is still the most present and influential, although its presence and role are diminished compared to the watershed years of George W. Bush. The United States pulled out of Iraq in 2011 (although it had to return in 2015) and Afghanistan in 2021. Successive U.S. administrations from Obama to Trump to Biden have recognized that while the Middle East remains significant, America’s main contest and challenge is further east with a rising China, and that America’s resources must be recalibrated accordingly. The United States is, in a sense, moving back to its pre-1990 level of involvement in the Middle East, which amounts to maintaining sizable diplomatic and economic relations, as well as significant naval, counterterrorism, and other military assets in the region.

An assertive Russia has certainly reemerged in the Middle East, but its return is limited. It has projected military power into Syria, and engaged via proxies in Libya, but its ambitions and capacities are restricted. The Russian economy is only around 7 percent of the U.S. economy and 10 percent of that of China, rendering it unable to compete on par with those two powers.

China, on the other hand, is still playing the long game in the Middle East, focusing on maintaining access to energy resources, finding markets for its products, and investing in its One Belt One Road infrastructure. While it is geopolitically challenging the United States in the South China Sea and over Taiwan, and in the realms of cyberspace, artificial intelligence, cell phone technology, and satellite security, it has chosen not to directly challenge America’s geopolitical role in the Middle East, at least for now. Although China disagrees with U.S. oil sanctions on Iran, American naval presence and policy in the Middle East generally serves Chinese interests as it ensures the free flow of much of the region’s oil to China and ensures the protection of trade routes through which much of China’s global exports flow. How China’s posture and strategy will evolve in 2030 or 2040 is harder to predict.

Navigating the Road to 2030

In the long run, a regional order would need to include all the main Arab and non-Arab states of the region, but given the current differences and divergences, one could suggest a three-track way forward. First, the Arab League should be strengthened and leveraged as a mechanism for rebuilding and enhancing intra-Arab cooperation in order to better face the myriad socioeconomic, security, and environmental challenges of the near future. But the Arab League—in effect, its main leaders—must also better articulate what future it is promising to the region’s youth. We have seen how the gap between youth ambitions and conditions led to wide-scale uprisings in the past decade, and such frustrations might boil up again. For example, what message are the Arab states that dominate the Arab League sending to the region’s youth if they are contemplating readmitting the Syrian regime, after all the ways it has decimated its own population, into the League? Intra-Arab state cooperation is necessary, but the Arab League and its main leaders going forward need to make clear what future they are proposing for the Arab World, if this cooperation is to build stability in the long run. Second, until one can imagine Iran and Israel participating in the same regional forum, the two tracks might need to be kept separate. This could include one regional forum that includes the Arab states, Turkey, and Israel. This platform could be used to address differences, work toward solutions to intractable problems—most notably, the rights of Palestinians to self-determination—and potentially build on common interests. A separate regional forum, including the Arab states, Turkey, and Iran, could also work to reduce conflict, enhance trust and cooperation, and build on common interests. Over time, whether enough progress could be made to merge these two into one overarching regional order is hard to predict, but at least it will be building the pathways and habits of intra-regional cooperation across a wide cross section of states.

Regional cooperation is essential to creating lasting stability, and the same can be said for the international relations of the Middle East. The region must integrate more fully into the global economy, must be a leader in energy transition, and must build fruitful relations with the major economies of the world. But Middle Eastern leaders should also be aware of the need to prevent global competition from sparking division and conflict within the region. This certainly was the case during the Cold War, and as the United States and China face off over the next few decades, history could very well repeat itself. As they navigate the next decade to 2030, regional leaders must figure out how to build and balance their global relations so as to reap the fruits of global economic and technological integration without getting dragged into global rivalries that could take the region down the path of more division and internal conflict.

The challenges of the coming decades will not be easy for the Middle East, nor for any region, to confront. But they will be nearly impossible to overcome if the region’s states remain mired in division and conflict or if global powers choose, once again, the Middle East as a battleground. Building a regional order and enhancing regional cooperation and integration, while dissuading global powers from exporting their differences to the region, is an urgent necessity if we are to stop our region from sliding into chaos. Also, giving our younger generations the means to confront and overcome the challenges lying ahead is a step in the right direction. If done correctly, it is possible to build a future of security, prosperity, and self-actualization together.

Paul Salem is the Vice President for International Engagement. He served previously as MEI’s President and CEO. He is currently based in the Middle East and works on building partnerships throughout the region. His research focuses on issues of political change, transition, and conflict as well as the regional and international relations of the Middle East. Salem is a frequent commentator on US and international media, and is the author and editor of a number of books and reports including Escaping the Conflict Trap: Toward Ending Civil Wars in the Middle East (ed. with Ross Harrison, MEI 2019); Winning the Battle, Losing the War: Addressing the Conditions that Fuel Armed Non State Actors (ed. with Charles Lister, MEI 2019); From Chaos to Cooperation: Toward Regional Order in the Middle East (ed. with Ross Harrison, MEI 2017), Broken Orders: The Causes and Consequences of the Arab Uprisings (In Arabic, 2013), “Thinking Arab Futures: Drivers, scenarios, and strategic choices for the Arab World“, The Cairo Review Spring 2019; Bitter Legacy: Ideology and Politics in the Arab World (1994), and Conflict Resolution in the Arab World (ed., 1997). Prior to joining MEI, Salem was the founding director of the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, Lebanon between 2006 and 2013. From 1999 to 2006, he was director of the Fares Foundation and in 1989-1999 founded and directed the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, Lebanon’s leading public policy think tank. Salem is also a musician and composer of Arabic-Brazilian jazz. His music can be found on iTunes.

Read More