Saudi Arabia’s Post-Oil Future

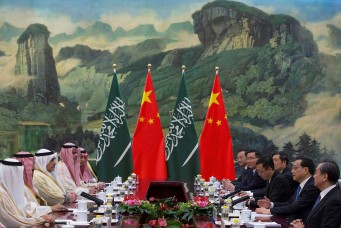

The story behind Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman Bin Abdelaziz Al-Saud’s vision to take the country into the future

Logo of Vision 2030 at a news conference, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia June 7, 2016. Faisal Al Nasser/Reuters

The euphoria that accompanied the launch of “Saudi Vision 2030” has begun to dim in the face of fundamental challenges. Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman Bin Abdelaziz Al-Saud’s ambitious plan to steer the country’s economy away from oil dependency and through an era of austerity seemed to offer a much-needed roadmap for overdue reforms. The plan’s measures include new taxes on foreign workers (the majority in the private sector), raised visa fees, reduced public salaries and hiring, and a gradual withdrawal of energy subsidies.

The call for austerity had an inauspicious start: soon after the launch of Saudi Vision 2030, foreign media reported on the continued lavish spending of both Prince Mohammed and his father, King Salman Bin Abdelaziz Al-Saud. Critics of the economic reforms cite the government’s precipitate approach and the absence of the necessary legal or political guarantees to ensure accountability or sustainability. Prince Mohammed, appointed deputy crown prince in 2015 after his father ascended the throne, consolidated the regulatory and executive power of the government under his direction in the Council for Economic and Developmental Affairs. To much of the public, the reforms seem to be reallocating money from one place to another, rather than investing in privatization.

The immediate outcomes of the economic reforms on the labor market to date are counterintuitive. The government is mainly targeting the private sector for taxation. Unfortunately, the private sector is rather weak and highly dependent on governmental contracts. In addition, weak labor regulations and the lack of unions undermine workers’ rights in labor disputes. The government suspended payments to major private contractors in 2016, leaving thousands of foreign workers unpaid for months and without legal redress. Some took to the streets in anger and were imprisoned and flogged for destroying public property. When foreign governments intervened, King Salman allocated $266.5 million to settle cases, and later replaced the minister of labor over rising unemployment among nationals, which had reached 12.1 percent.

The situation is also dire for Saudi citizens in the private sector. Saudis occupy 70 percent of jobs in the public sector and less than 15 percent in the private sector. Since 2011, the state adopted measures toward the “Saudization” of jobs in the private sector. Despite the state efforts to spike Saudization, private sector employers continue to prefer lower-paid foreigners over Saudis. Recently, the Shura Council criticized the Saudi Arabian General Investment authority for a failed strategy that caused one out of eight foreign investors to end their business in Saudi Arabia. It was more likely that the rising cost of operation and the taxation of foreign workers is what drove investors away.

A recent revision of Article 77 of the labor law granted employers the right to terminate workers’ contracts for modest compensation. This caused a 38 percent drop in Saudization. In the last nine months alone, 50,000 Saudis’ contracts were terminated and 170,000 new foreigners were hired. It is therefore unlikely that the projected 450,000 jobs for Saudis will be created in the private sector by 2020. Small measures were planned to absorb the public fury, such as the Shura Council meeting with unemployed Saudis, after receiving thousands of petitions, and a decision to suspend companies accused of blanket layoffs. However, businesses continue to terminate employment contracts to manage the rising cost of operations.

The state’s cautious manner in addressing the position of women was evident in how it managed women’s participation in the workforce, one of the lowest globally. Though Saudi Vision 2030 places an ambitious objective of “unlocking the talent, potential, and dedication of our young men and women,” it does little to translate it into reality. The plan targets only an 8 percent increase in women’s workforce participation.

Saudi Arabia also chooses to ignore the grassroots advocacy campaigns to further women’s rights, for example by abolishing the ban on women driving and the male guardianship system. Nor does the kingdom have a codified personal status law supporting women’s family rights. The state’s investment in the ride-hailing company Uber, with women representing 85 percent of its clients, ensures a long shelf life for the driving ban.

Women are eager to join the job market. Ironically, some women have even found opportunities operating food trucks—even though they cannot drive the vehicles themselves. Though the state has placed several women in top positions, appointments should never be confused with representation. Four of the first women members in the Shura Council submitted a request to the king to be relieved from their duties due to obstructions in reforming women’s legal rights. The state continues to treat women as avatars of the kingdom’s Islamic and tribal identity.

The state has always managed reforms in a way that maintains the ultimate control of the ruling Saudi family. Even when terms like “our people” and “our society” are used, as in Saudi Vision 2030, public participation remains symbolic rather than genuine. A fierce domestic resistance has developed against selling shares in the oil giant Aramco because of concerns about losing control of the sole resource of the nation to foreign investors.

The monarchy’s system of patronage, based on loyalty rather than public rights, is hard to maintain when money is in short supply. The Saudi royal family has long deferred political reforms—particularly those affecting women, youth, and minorities—based on the premise that they may trigger a backlash among religious conservatives, an argument which is easily refuted considering the little to no resistance following decisions to curtail the religious police’s powers, or to allow concerts and public performances. Failure to address human development in its true essence—job creation, social security, and representation in decision-making—is the hallmark of a blurry, unsustainable vision for the future.

Hala Al-Dosari is a visiting scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter