Maintaining the U.S.-Saudi Relationship

The once booming strategic alliance between Riyadh and Washington has weathered a number of regional storms but is beginning to show wear and tear.

The US-Saudi partnership that began in the 1940s today bears all the hallmarks of a barely functional and unhappy, but essential marriage of convenience. The same basic interests that drove the two parties together in the first place have maintained the partnership through decades of tension, upheaval, and difference; and they are likely to allow it to persist in the present era, despite virtually unprecedented levels of distrust that have festered in recent years.

Grave historic rifts occurred during the 1973 oil embargo, which gave rise to the highly unflattering cliché of the Arab “oil sheik” in US popular culture; the 9/11 attacks, which produced a great deal of resentment on both sides, particularly in the United States; and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, which Saudi Arabia strongly opposed and most Americans have come to deeply regret.

But resentments reached a new crescendo on both sides during Barack Obama’s second presidential term and the one-term presidency of Donald Trump.

During Obama’s second term, the Saudis and other U.S. partners in the Middle East, including Israel, were unnerved by nuclear negotiations with Iran and the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreement between Tehran and the P5 +1 international consortium, most notably the United States. The Saudis feared that, at its least, the agreement would greatly strengthen Iran at their expense, having been crafted without their input or best interests in mind. At worst, it signaled a long-term intention on the part of some or all of the Obama administration to try to develop a long-term understanding that would effectively create an Iranian-American security regime in the Gulf region. This was nightmarish and catastrophic from the Saudi point of view. In any event, that never materialized and Iran even proved unwilling to discuss anything beyond the nuclear agreement. But Saudi Arabia was shaken by the prospect they suspected was all-too-real.

Saudi disappointment with Washington was, if anything, outdone by the anger many Americans, especially Democrats in Congress—but also some key internationalist Republicans—developed toward Riyadh during the Trump administration. The strong identification between Trump and his family—particularly presidential son-in-law Jared Kushner—with the Saudi government—particularly Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman—fed a narrative among Democrats that recast much of the U.S.-Saudi partnership as a dubious Republican policy orientation, and, indeed, a Trumpian error, rather than a decades-long bipartisan position.

These concerns took hold in the early days of the Trump administration when the new president’s first overseas trip was a pomp and circumstance-filled trip to Saudi Arabia. Added to that were increasing concerns about the human costs of, and the use of U.S. weapons in, the poorly-understood Yemen war. Almost all Democrats and many congressional Republicans were outraged at the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Perceptions that Trump was effectively covering up for Prince Mohammed reinforced the impression of an unhealthy partnership and heightened disdain for the Saudi leadership. Human rights concerns, including the jailing of women’s and human rights activists; a widespread crackdown on political dissent in the kingdom; and accusations that Saudi diplomats had helped Saudi citizens evade trial on serious criminal charges in the United States all made matters worse.

Fears of a U.S. Exit

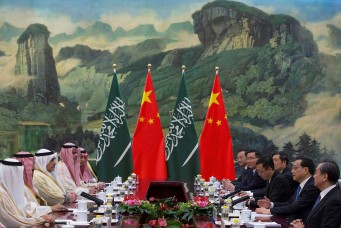

Meanwhile, doubts among the Saudis continued to grow. For all his friendliness, Trump had not allayed their fears that the United States is slowly withdrawing from the Middle East, and has been an unreliable and unwise ally. The Saudis also were concerned that the Democrats may well favor Iran and Islamists like the Muslim Brotherhood. Virtually all U.S. partners in the Middle East have been engaging in a concerted effort at strategic diversification, hedging against the relative decline in American power, global and regional influence, by seeking to increase their options and further develop independent assets. That has included Gulf Arab and Israeli outreach to new global partners like Russia and China; and to each other, as in the case of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Israel.

The days of simply relying on the United States to jump in and rescue Arab states from Middle East crises are plainly over. And going as far back as the George W. Bush administration, Washington has also been demanding more “burden-sharing” by its partners around the world, particularly in the Middle East.

In short, when Joe Biden was inaugurated in January 2021, he inherited a U.S.-Saudi partnership that was arguably in the worst condition, at least between governments, since it began almost 80 years ago. Yet, the relationship remains essential to both parties.

Despite achieving relative energy independence, if the United States wishes to continue to play a global balancing role, maintaining a dominant position in the Gulf region, which is still the beating heart of the global economy (particularly in East and South Asia), is essential. A “pivot to Asia” and a new emphasis on “great power competition” with China does not eliminate the importance of the Gulf region to the United States. On the contrary, because of the centrality of Gulf energy supplies to the economies of East and South Asia, it actually reinforces it.

Saudi reliance on the United States is even more fundamental, since Riyadh requires an international partner to help ensure its basic national security and, despite Saudi doubts about Washington, it’s obvious that no other state is currently either able or willing to fulfill this role. And, certainly, Saudi Arabia is in no position to guarantee its own security, as a failed war in Yemen and disturbingly successful Iranian drone and missile attacks against Saudi Aramco facilities in 2019 clearly demonstrate.

So, even if this is an unhappy marriage, divorce is not an option for either side – assuming Washington does not want to actually embrace a neo-isolationist policy (for which there is, thankfully, little support in Washington).

Relationship Reset

Yet, a reset was obviously required, both politically and strategically. Between them, the Biden administration and the Saudi government have taken a number of important steps to repair the relationship or create the political and diplomatic conditions that will allow the partnership to continue despite the accumulation of mutual doubts and grievances outlined above.

The main onus is on the Saudi government to show that it understands that repairs, if not amends, need to be made, and that business as usual under Trump could not continue without adjustment under Biden.

The first dramatic step came in the final days of the Trump presidency with the ending of the embargo of Qatar imposed by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt—known as the Quartet. While this embargo, which began in 2018, was initially supported by Trump, at least rhetorically, neither the State Department nor especially the Pentagon approved. The US military, in particular, strongly opposed the boycott that threatened to complicate easy interoperability and communications between key military hosting sites in Qatar, Bahrain and the UAE. Eventually, this perspective won, and although the Trump administration pressed for an end to the embargo, it didn’t prioritize the issue. Biden, however, made it clear he did not wish to inherit this difficulty, and Saudi Arabia, evidently realizing that there was little more to be gained by extending the boycott, agreed to end it. The UAE initially declined to sign on, but when they realized they could not stop a bilateral Saudi-Qatari arrangement, the UAE convinced Saudi Arabia to delay the process slightly and ended the boycott by the whole Quartet.

In addition, Saudi Arabia released several key prisoners, including the famed women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hatloul, several Saudi-American dual nationals awaiting trial, and others. It commuted harsh sentences against young Shiite activists and quietly reassured members of Congress that its diplomats would not be helping Saudi nationals evade trial in the United States. The Saudis also tried to draw attention to the dramatic and impressive social and cultural reforms, especially on culture, arts and gender, that really have been taking place in Saudi Arabia in the past few years. Finally, and crucially, Saudi Arabia proposed a cease-fire in Yemen and managed to begin to recast the war in that country not simply as a reckless and cruel gamble by Prince Mohammed, but as an actual conflict with a very dangerous and fanatical Iranian-allied militia group on the other side. Most importantly, perhaps, it has made a lot of headway in demonstrating the extent to which the Houthi rebels are the main obstacle to a peace agreement in Yemen and, above all, the orderly withdrawal of Saudi Arabia from that conflict.

Essential to U.S. Interests

Meanwhile, the Biden administration has begun carefully and systematically making the case to Democrats in Congress and beyond that maintaining the relationship with Saudi Arabia is essential to U.S. foreign policy. The administration, after all, has identified two key priorities in the Middle East, both of which most Americans would find reasonable: 1) ending the war in Yemen; and 2) revising nuclear diplomacy and the JCPOA with Iran. Both of those goals require Saudi cooperation. In Yemen, Saudi Arabia is one of the main parties directly involved. With regard to nuclear diplomacy with Iran, Saudi Arabia is a crucial secondary player. It won’t be at the table, but the dangers of lacking Saudi, Emirati and, above all, Israeli buy-in for an agreement was amply demonstrated by the collapse of the JCPOA under Trump and the strong international and domestic support for his withdrawal from the agreement.

Most importantly, Biden has been attempting to effectively move past the Khashoggi murder and convince Democrats that what can be done has been done and that the issue is, in effect, resolved as a bilateral matter at the highest level between Washington and Riyadh. He released the unclassified version of the intelligence summary on the killing, which, predictably, added virtually nothing that was not already known about the crime. The circumstantial case, particularly based on logical inference, against Prince Mohammed was neither strengthened nor weakened by the information, and even the Prince has acknowledged that as the key official, he bears responsibility. Biden also imposed travel bans and other sanctions on 76 Saudi officials and instituted a new kind of visa restriction, which it called the “Khashoggi ban”, against officials credibly accused of persecuting dissidents and journalists around the world.

It’s likely that by withholding the release of unclassified intelligence summary—which is required by law—Trump kept the Khashoggi murder alive as a controversy. This assured much more political and media attention on the issue would continue, and in turn intensified the damage it was doing to U.S.-Saudi relations. With the report unreleased, there was no way of putting the issue to rest. By releasing it and imposing various penalties and sanctions, although not enough for many critics of Saudi Arabia and Prince Mohammed, Biden was essentially seeking to send a series of messages: we take the issue seriously; we are not pretending not to know what happened or who was responsible as Trump did; we are taking some actions that are meaningful; but we are not going to sacrifice this key bilateral relationship because of a single assassination. The intention is clearly to put the issue to rest between the governments, and it may well have succeeded. Yet, more work will be needed before Prince Mohammed, who is almost certain to become king sooner rather than later, can anticipate a courteous welcome in the United States.

Continued congressional opposition to U.S. weapons sales not only to Saudi Arabia but even to the UAE suggests that the bilateral relationship remains in considerable difficulty in Congress. Meanwhile, Saudi doubts persist about Washington’s will and ability to act decisively to help its partners and friends in the region. These doubts may have even deepened when Trump took no action in response to the Iranian attack on Saudi Aramco’s oil facilities. The spectacle of the Biden administration returning to the nuclear negotiating table with Iran also revives bitter memories of the Obama era, so mutual skepticism remains a serious issue.

Arab Interests at the Table

Traditional U.S. Middle East allies like Saudi Arabia, and even Israel, discovered in 2015 that, as one would expect, they have no veto on US actions or bilateral and multilateral decisions regarding Iran. Their doubts did nothing to prevent Washington from entering into the agreement. However, the biggest problem from the Saudi perspective was not the nuclear agreement itself or even the benefits Iran derived from sanctions relief and enhanced international legitimacy as a result of the JCPOA. Instead, it was uncertainty about underlying U.S. intentions and attitudes regarding Iran and Saudi Arabia. In brief, the Saudis feared being abandoned either in favor of Iran or at the behest of Iran.

It’s imperative that U.S. leaders learn from these mistakes. While Saudi Arabia and other traditional partners will not be at the negotiating table with Iran and the rest of the P5 +1, it’s important for Washington to have a parallel dialogue with Riyadh, to make sure that Saudi Arabia experiences no sudden surprises from the negotiation and is reassured that any agreement will not come at the expense of their fundamental national security. That shouldn’t be too difficult because Saudi Arabia has an obvious interest, too, in Iran not becoming a nuclear power. If Riyadh is reassured that this is really what Washington is trying to achieve, and nothing more or less than that, anxiety should be greatly assuaged.

But Saudi Arabia, too, needs to reassure Washington about its intentions and conduct. In particular, ending the war in Yemen is essential. Furthermore, if Saudi Arabia is really trapped in Yemen by Houthi intransigence, this challenge could be demonstrated to an engaged and focused United States. But it is imperative for Riyadh to effectively demonstrate that Saudi Arabia wants to end the war and leave Yemen. And while the Khashoggi murder indicates that Washington is not going to fundamentally rethink the core partnership because of specific human rights abuses, every egregious case harms the relationship and makes it harder to move toward the day that not only is the US-Saudi relationship restored to its former glories, but that senior leaders like Prince Mohammed will be once again be welcomed in the United States.

Hussein Ibish is a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington and a weekly columnist for Bloomberg Opinion and The National. His work focuses on the role of Arab Americans and he is the author of What’s Wrong with the One-State Agenda? Why Ending the Occupation and Peace with Israel is Still the Palestinian National Goal. On twitter: @Ibishblog.

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter