Mirroring the Other

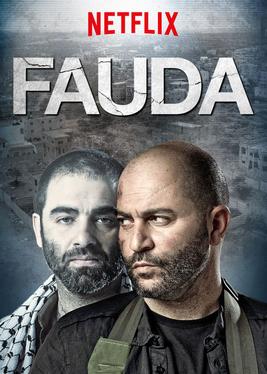

Fauda, Netflix’s hit TV series on Israeli undercover operatives in Palestine, presents Palestinian and Israeli characters that have nuanced emotions and desires; yet the show still otherizes Arabs and justifies Israel’s actions in the West Bank and Gaza.

I was prepared to hate Fauda. The Israeli political thriller about counter- terrorism agents who impersonate Arabs during their operations had been getting a lot of critical buzz since its 2016 Netflix debut. Yet, while I found its premise disturbing, Fauda (Avi Issacharoff, Lior Raz, 2015) had me riveted.

True to its name, which means chaos, confusion, and anarchy, Fauda is a tumultuous descent into the turmoil and lawlessness connected to the enforcement of Israel’s more than fifty-year occupation of the Palestinian territories. Its relentless brutality was difficult to watch, but I could not turn away from its achingly familiar sights and sounds of Palestinian life. Maybe it was Fauda’s unexpected, and perhaps unintended, focus on the linguistic and cultural connections between the protagonists that made the series heartbreaking, and perversely, tinged its mind-numbing chaos with a glimmer of hope.

Fauda is not a coexistence story. It is an Israeli story, made by Israeli producers, who wanted to bring the story about the Mistarvim—Israeli undercover units who impersonate Arabs in order to track, kidnap, or kill suspected Palestinian terrorists—to an Israeli audience. It is an unflinching recreation of what goes on at the tip of the occupation’s spear. In one brutal scene after another, the Mistaravim—a Hebrew verbal noun meaning “those who become Arabs”— slip into Palestinian mosques, hospitals, swimming pools, and obstetricians’ offices, to snatch up potential informants, or carry out an extra-judicial execution at point-blank range.

The series makes no effort to conceal the scale of the carnage, or its gut-wrenching impact on the victims and their families. But even if the series suggests that terrorists may also love their mothers, children, or brothers, there are no apologies for the unit’s tactics or the collateral damage they inflict on the population. On the contrary, the show never misses an opportunity to remind the audience why these units exist: Israelis have been killed, and their deaths cannot go unpunished. Palestinian casualties, on the other hand, are presented as regrettable necessities.

To be fair, unlike some of the more jingoistic variants in the “counterterrorism as entertainment” genre, Fauda’s Palestinian characters have prominent, compelling roles and are played by accomplished Palestinian actors. It also shows the Israeli characters breaching norms and making morally dubious choices. Nevertheless, the series never truly deviates from the Israeli narrative, and spares little artistic effort to ensure that the audience can distinguish between the tragic heroes, whose excesses should be forgiven, and the terrorists, whose inchoate humanity is tainted by fanaticism.

For example, Doron Kabillio, the Israeli lead played by Fauda’s producer and veteran Mistariv Lior Raz, makes his first appearance bathed in warm green sunlight while he playfully sprays his children with a garden hose. In contrast, his Palestinian counterpart, the “Panther,” the nickname for Abu-Ahmed, who is also known as Hamas mastermind Taufiq Hamed, played by Hisham Suliman, literally emerges from the darkness, unwinding a keffiyeh from his face. It is no surprise that the Palestinian heroine, the unveiled, French-educated medical doctor Shirin El-Abed (played by Laëtitia Eïdo), prefers the affections of the wine-making Doron over marriage to the “Panther’s” scraggly bearded henchman, who also happens to be her cousin.

Yet despite these thinly veiled tropes, Fauda also speaks to us in Arabic. In some episodes, upwards of 70 percent of the dialogue is in Arabic which, at a time when Israel’s 2018 nation-state law demoted the status of the language from official to “special” language, is a provocative statement. Not only is Arabic the language of conversation between the Palestinian characters, it is also the lingua franca for the show. Consistent with Fauda’s conceptual premise, the Israeli characters also speak Arabic—not just a few phrases, but well enough to blend into a family wedding, or pass as a member of the Palestinian police or preventive security services. And while not made explicit until season two, the reason the Mistarvim are so facile with the language, as well as the culture and social norms, is not that they are Israelis who can “become” Arabs, it is because they are Arabs. Like the producers, as well as some of the actors in the series, the members of the unit presumably grew up speaking Arabic at home—maybe because their parents, like Doron’s father, Amos, immigrated from Baghdad, or from other parts of the Arab World, or whose families were always part of the multifaith fabric of pre-Mandate Palestine.

What Fauda also hints at, although very subtly, is that the Arabness of the main characters is both the reason they are drafted into these elite units, but also a source of marginalization within the broader Israeli society. If they were not in the unit, the commander jokes, they would likely “still be out on the streets stealing radios.” In the unit, however, they can be counted on to do the dirty work. In comparison with the uniformed soldiers in the command-and-control center, the unit’s agents always appear a little bit rougher, a little less rational, and more likely to come undone. In other words, the creators of Fauda imply it’s not just their knowledge of Arabic, but their Arabness that places the Mistarvim in the vanguard of the occupation.

In some ways, Fauda is almost a confession about the limits of Israel’s massive military and technological superiority when it comes to enforcing the occupation. Yes, its extensive network of drones, internet, and phone surveillance can track every Palestinian’s every move. But translating that information into “quiet,” or the opportunity for Israelis to enjoy a normal and prosperous life on their side of the wall requires sending in what Avichay (played by Boaz Konforty) refers to as “the dogs”—people who won’t pause or ponder the moral implications, but just barge in and execute the kill.

In addition to brute force, the Mistarvim also deploy crippling psychological pressure. Some of the most unsettling scenes in the series are the interrogation sessions, which are typically conducted by the ruthlessly avuncular Captain Ayoub (played by Israeli actor and one-time drag queen Itzik Cohen). With chilling precision, Captain Ayoub assesses which nerve to press in order to bring his victims to their knees. Sometimes he dangles a carrot, or reveals a potentially devastating piece of information to serve as a stick. Alternatively, he just chips away at weaknesses he already senses exist, such as playing off internal divisions with the different Palestinian factions to give his informant a justification for ratting out a former rival, or pushing the wife of a Hamas activist to admit to herself what she has always known: that as long as they remain in Palestine she and her children will never have the opportunity to lead a normal life.

Of course, the weaponization of familiarity is a two-way street. The Israelis are not the only ones who have developed an understanding of their adversaries and leveraged that knowledge to their advantage. During one particularly savage interrogation scene, a Hamas operative unhinges Captain Ayoub by revealing he knows his real first name, and much of the plotline in season two actually revolves around the Palestinian characters attempting to beat the Mistarvim at their own game. Such actions are undertaken by Panther’s successor, “Abu-Saif Al-Makdassi” (played by Firas Nasser), and his small band of junior Hamas defectors, who learn Hebrew and dress up as observant Jews to pass through Israeli checkpoints. They also conduct surveillance, recruit informants, and manage to penetrate the innermost sanctuaries of the unit’s lives. Predictably, their efforts backfire and produce lethal consequences for themselves or their families.

Throughout the series, Captain Ayoub also meets with “Abu-Maher,” a thinly veiled caricature of the former head of Palestinian Security Services Jibril Rajoub. During their conversations, the two circle each other like a pair of gladiators. They sip coffee, trade pleasantries, and warily offer up snippets of information, or promises of cooperation—always trying to reveal less than they learn, or get more than they give away. Ironically, it is often Abu-Maher who gets the upper hand. He parlays requests from Captain Ayoub to leverage against Hamas, and cleverly dupes Captain Ayoub into revealing that the Israeli they caught in Nablus was one of his operatives. Yet, while the relationship is tense, and carefully staged, there is also a genuine level of respect— however begrudging.

And while most of Fauda is about showing the different ways familiarity breeds carnage, or the occasional act of cooperation, it also fosters connection— however brief or bittersweet. After inducing Dr. Shirin to assist in the capture of her cousin—who she had to marry after it was revealed Doron was a Mistariv and not a member of the Palestinian security services—Doron brings her to his father’s place in the Negev desert to await her deportation. Although Doron’s father, Amos, warns his son that nothing good will come out of his tryst with Dr. Shirin, he also takes obvious delight in her presence. They chat over coffee, he quizzes her on the flavors in his cooking, and shares stories of growing up in Baghdad. In turn, she prepares him a sumptuous breakfast. When Amos approaches the spread, he runs his hand over the embroidered cloth she placed on the table with nostalgic awe: “It’s been years since this has been here,” he muses. She responds with a shrug, “I found it in the drawer.”

What seems like a touching but innocuous exchange between two putative strangers actually reveals something quite profound about the nature of Israeli–Palestinian tragedy. Contrary to what the Spectator’s columnist James Delingpole argues, Fauda does not “tell the truth about the conflict” by showing the Israelis and Palestinians as two peoples “impossibly riven by a set of inimical values.” Instead Fauda actually reveals how much they have in common, and how fundamentally similar they are—right down to the contents of their kitchens.

Whether or not this is an unconscious admission of reality, the Israeli and Palestinian characters in Fauda come off as mirror images of each other. Both are driven by deep bonds of honor and loyalty, and when confronted with loss or betrayal, both are quick to rage or crave revenge. And yes, both love their families and are prepared to make sacrifices for the good of their country.

Again, Fauda was not meant to be a coexistence story, but when all the shooting is done and you listen to how the characters speak, and what they say to each other, Fauda reminds us that there is more than the dispute binding the characters together.

Allison Hodgkins is an assistant professor of international security and conflict management at the American University in Cairo (AUC). Prior to joining AUC, she directed the CIEE Study Center at the University of Jordan from 2006 to 2012, and served as academic director at the Middle East Peace and Conflict Studies program of the School for International Training between 1995 and 2001. She taught at the University of Jordan, Bentley College, and Northeastern University. She is a regular contributor at Political Violence @ a Glance. On Twitter: @ABHodgkins.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter