Paving the Way for Bouteflika’s Succession

In an effort to smooth the way for Bouteflika’s successor, the Algerian elite are taking modest but significant steps to open the political sphere and undertake cautious economic reforms.

As the question of succession dominates public debate in Algeria, what has been mostly a rumor for years is gradually turning into a broader debate capable of polarizing the political class. Could Saïd Bouteflika succeed his brother Abdelaziz as president of Algeria when the moment comes? Several hints have been dropped in the press by pro-Bouteflika outlets and anti-regime journalists to support or attack this idea. While often discussed in abstract terms, this previously unlikely scenario is becoming increasingly conceivable, with many observers seeing a series of reshuffles within the security sector and liberalizing measures as preparation for this delicate succession.

Whether for Saïd or someone else, what is clear is that the ruling factions are working on smoothing the transition to a post-Bouteflika Algeria. Their priority is to lay the foundations for an orderly succession that will minimize any risk to their vested interests. The presidential faction, the army, and pro-regime businessmen are unwilling to put forward names at this early stage, because it would spoil their preferred successor’s chances of winning—it would be too easy for other clans and constituencies to undermine their candidate’s credibility. Moreover, the regime is still going through a delicate reorganization, particularly as the formerly all-powerful military intelligence is being tamed. The presidential faction’s preferred plan is likely to have Saïd Bouteflika succeed his brother as president, but before publically putting his name forward the regime needs to clear the way for this transition.

The regime is working on two main tracks to prepare the population for the transition in generally—and for Saïd in particular. First, the authorities are engineering a carefully controlled political opening aimed at winning over a series of key constituencies. This includes promoting an empty slogan of building a civilian state and proposing a series of mostly cosmetic constitutional amendments. In particular, the amendments aim to convince the Amazigh-speaking population, women, and local businessmen that their demands have been met—and it is therefore in their interest to support the factions in power by recognizing the Amazigh language as official, promoting women’s rights and representation in the public sphere, and reinforcing provisions for the private sector. In addition, a series of measures try to appease the formal opposition by guaranteeing its rights of expression in the media and in parliament while isolating the extra-parliamentary opposition (the former members of the outlawed Islamic Salvation Front, for example). In recent weeks, state-owned television channels have been airing talk shows where opposition politicians have been free to express their anti-regime views—an unusual move aimed at underlining the new political environment in Algeria. The regime hopes to market the successor to Bouteflika as one who will continue these policies of ostensible reform.

Second, the authorities have postponed the adoption of politically sensitive austerity measures, despite the collapse in oil prices and the widening fiscal deficit. In a country beset by recurring outbursts of violent unrest, spending cuts could have a devastating impact on political stability and undermine the prospect of a smooth transition. By tapping into the national oil fund (a quasi-sovereign wealth fund known as Fonds de Régulation des Recettes, FRR) to fill this gap, the government has managed so far to protect welfare spending from cuts. Combined with very low levels of external debt, the authorities are in a position to postpone any painful spending cuts until after the presidential succession is complete by depleting the FRR and borrowing externally. This strategy should buy the regime sufficient time to manage the transition and avoid any major bouts of unrest, as the implicit social contract between the regime and the population—high levels of spending in exchange for limited democratic accountability—remains intact.

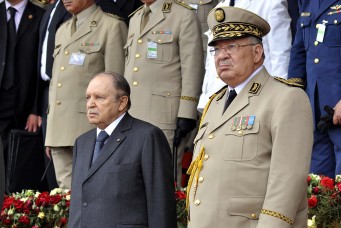

That said, two variables could undermine this strategy: the support of the army and the success of the timid economic liberalization plan. First of all, the support of General Ahmed Gaid Salah, chief-of-staff of the army and de facto defense minister, will be essential to whatever candidate the other factions choose. In the past, military intelligence has played a key role in opposing the idea of Saïd becoming president. However, the removal of General Mohamed “Toufik” Mediene as head of the Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS) at the hands of General Gaid Salah in September 2015 means that the army has now replaced it as the main interlocutor of the presidential faction. While the DRS acted as the main counterweight to the president by undermining the latter’s attempts to monopolize power and impose a successor at the head of the state, the army has been remarkably cooperative and loyal to the Bouteflikas. So far, these two actors have cooperated closely, as General Gaid Salah owes the Bouteflikas his successful career and rise to power. However, the presidential faction would find it difficult to overcome the opposition of the army, the main pillar of stability in the country, if he were to say “no” to Saïd Bouteflika succeeding his brother. While General Gaid Salah and the Bouteflikas are allies, it is possible that a disagreement over the choice of the next president could end their partnership.

Likewise, in recent months the government has unveiled a limited economic liberalization to compensate for the sluggish economic outlook and the end of the oil bonanza. The combination of low oil prices and the need to shore up regime legitimacy ahead of a delicate political transition are pushing Algeria’s ruling elite to implement a policy of cautious reform. For the first time, authorities have authorized private businesses to borrow abroad and set up and run industrial estates. Moreover, the 2016 budget paves the way for the partial privatization of state-owned firms, thus marking a major U-turn in Algeria’s economic policy. Finally, the government has lifted the ban on consumer credit but restricted its use to purchasing locally produced goods, with the aim of boosting domestic production. While these measures remain timid and do little to promote exports, they mark a significant break from the previous fifteen years of state intervention and regulation of the economy.

These modest measures show that the ruling factions desperately need to appease large sections of the population and are therefore ready to make concessions to these constituencies. Although the planned openings seem quite small, they are actually quite significant in historical terms. Domestic pressure on the Algerian regime is empowering those constituencies and regime officials favorable to gradual reform. While the outcome of the transition is still uncertain, for the first time the regime is showing a cautious willingness to tackle some of the issues that have historically restricted its political and economic evolution.

This article is reprinted with permission of Sada. It can be accessed online here.

Riccardo Fabiani is a Senior North Africa Analyst at Eurasia Group.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter