A Visualization of Egypt’s Economic Performance During COVID-19

In this infographic article, we illustrate Egypt’s economic performance, pandemic response, and future based on commentary from IMF economist Said Bakhache.

A man walks past a currency exchange bureau in Cairo, Egypt, May 6, 2018. Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters

Every corner of the world has been impacted by the pandemic’s effect on the economy, but the extent to which they have taken a hit has varied from country to country. Egypt, for example, has so far done better than others in the region in part due to the fact that a full lockdown was never implemented, but also because of its enhanced macroeconomic resilience by way of recent reforms.

In a webinar hosted by the Cairo Center for African Studies “Assessing the Economic Impact of COVID-19 and Policy Responses in Africa”, Said Bakhache, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) senior resident representative in Egypt, reviewed how Egypt’s economic performance facilitated pandemic-response and offered some of his recommendations for the future.

Difficult Decisions

Egypt went to the IMF in 2016 for a $12 billion loan. Although a difficult decision, Bakhache believes that if Egypt hadn’t taken the loan at that time “the situation would be very dire”. For example, from 2012 to 2015, central bank reserves were critically low at $15-16 billion, falling below the threshold needed to cover three months’ imports. Furthermore, the value of the pound was artificially inflated to allow the importing of vital goods, and access to foreign currency outside of activities deemed essential was restricted.

As a result, Egypt undertook a series of reforms to restructure its economy. These reforms included floating the Egyptian pound, essentially doubling the cost of imports (and gains from exports) overnight. Fiscal reforms such as cutting and restructuring subsidies, especially energy subsidies on electricity and fuel, were pursued, and pensions were reformed. A slow privatization program, which is still underway, was initiated. The difficult question of Egypt’s notoriously low tax collection was also tackled with measures such as expanding the sales tax to cover services as well as goods through the newly-introduced value-added tax. Several other technical and regulatory reforms were also undertaken, such as increasing the central bank’s interest rate to attract portfolio investment. Spending on social security programs was also increased to 1 percent of the GDP—a measure which would have been considered off-brand for the IMF in the past. Indeed, programs such as Takafol and Karama, which provide cash transfers to orphans, the elderly and disabled, and families with students, have been continually expanded, currently reaching more than 3 million households.

These reforms, however, were austerely felt. The purchasing power of Egyptians was hard hit due to the flotation of the pound combined with subsidy cuts and tax increases, which exacerbated poverty and lowered the standard of living for almost all Egyptians. Nevertheless, the merits of the reforms were seen during the Covid-19 crisis. Bakhache said that these reforms generally made the economy more resilient, giving officials a “healthy policy space” to take the measures necessary to mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

For example, fiscal reforms especially with regards to energy subsidies led to unprecedented primary surpluses in the budget; in 2018, the Ministry of Finance announced that it had achieved a 0.2 percent primary surplus for the first time in fifteen years. On the monetary side, Bakhache said that reserves reached a comfortable position of over $40 billion from its lowest at 15 billion in 2014. Banks are also now in a “healthy situation,” he added. Moreover, inflation has gone down significantly since the flotation-induced spike, peaking at almost 33 percent in July of 2017 before falling to just over 4 percent this January.

Of course, Covid-19 produced a shock to the system that resulted in a big outflow of capital from Egypt, with, for example, portfolio investment, which is known as “hot money” due to the quickness at which it can enter and exit markets, going from $43 billion in FY18/19 to -$73 billion in 19/20.

Pandemic Response

Yet, the crisis was contained “a lot better than expected,” said Bakhach especially compared to other countries. The IMF economist believes that “Egypt is a great example of how to deal with a crisis but also how to address challenges that are looming”. He praised the government’s fiscal policy, allocating EGP 100 billion to combat the pandemic and mitigate its effects. For example, it extended welfare as part of the Takaful and Karama to an additional 142,000 households, serving 3.6 million Egyptians, gave EGP 500 to irregular workers for three months, increased tax exemptions, and raised health spending by 47 percent and that of education by 14.8 percent. It also earmarked contingency money for possible expansions in pandemic response.

Bakhache also praised Egypt’s proactive seeking of financing at the start of the pandemic, before the pressures of the pandemic intensified. Egypt went to the IMF for an emergency loan of 2.7 billion, in May 2020, and sought a 5.2 billion twelve-month Stand-By Arrangement that was approved in June. He expects that given the measures it took, Egypt will not need to go to the IMF again at this time.

However, the crisis is still playing out and Bakhache questions “whether the reforms of the past few years can still carry the Egyptian economy for the remainder of the crisis and beyond Covid”. He emphasized the need for continued reforms, despite having been the only country in the region to experience positive GDP growth in 2020.

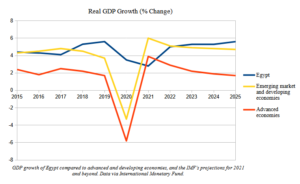

As seen in the graph below, Egypt recorded 3.8 percent GDP growth in 2020, ahead of the average for both advanced and emerging economies, where both groups recorded a contraction in real GDP. However, according to IMF projections, both country groups will exhibit a stronger recovery in 2021, with advanced economies achieving a 4 percent real GDP growth and emerging markets 6 percent. While Egypt is still above average in projections for the medium term, concerns remain over longstanding issues in the Egyptian economy.

Challenges Remain

Bakhache noted that there are still looming challenges associated with the growth outlook, drawing our attention to the less-than-promising investment, exports, and labor market situation. He said that growth so far has been driven by consumption, and points to the fact that 50 percent of investment in Egypt is made by the public sector. There is low private investment, with most foreign direct investment (FDI) mainly coming from the oil sector.

While one of the goals of the recent reforms was to spur industry to shift toward an (at least in part) export-oriented economy, this has yet to happen. Exports are low compared to any country grouping, and the trade balance is still a burden on the balance of payments. On average, as illustrated below, Egypt’s imports are $35 billion higher than its exports. “The ability for the Egyptian economy to integrate into the global value chain depends on the ability of exporters to import products on which they can add value and then export again”.

Sectors which have driven this growth, such as oil and tourism (pre-Covid), have been successful. Petroleum, for example, retains over a third of the share of proceeds from exports, as can be seen in the graph below. Bakhache believes the road to growth for Egypt is through diversification.

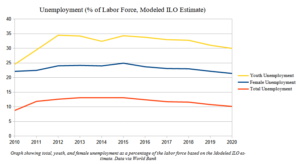

When it comes to the labor market, unemployment is declining, but youth unemployment is still very high at above 30 percent, and female participation in the market remains lower than desired at less than 80 percent. Moreover, Bakhache stated that the quality of jobs is generally poor, as many are in the informal sector, where there is no job security or labor protections. Bakhache also warned that the biggest issue facing the labor market is demographic, stating that Egypt’s working age population will increase by 30 percent in the next twenty years, and that the effects of this will be felt this decade.

This lends to reason why the private sector needs to be energized. While he recommended staying on the path of the current macroeconomic policy of treating the interest rate with caution, which has been gradually lowered from its peak of 19.25 percent to 8.75 percent, there is also a need to deepen reforms and empower the private sector. In that vein, the state’s role in the economy must be clarified, and regulatory and bureaucratic impediments to participation must be identified and eliminated. According to Bakhache, it is essential to “create the space and environment for the private sector to take advantage of these opportunities”.

On Poverty, Inequality, and Structural Reforms

Bakhache looks forward to the deepening and sustaining of efforts with regards to economic reform. When asked about how macroeconomic indicators reflect on the general well being of the Egyptian people, the IMF expert stated that there have been improvements in growth and employment, but that he would still like to see more spillover from strong macroeconomic indicators into more widespread and inclusive employment. He stated that the numbers are not completely reflective of the relatively worse situation on the ground.

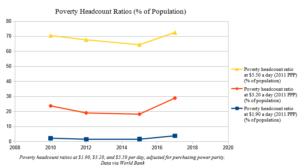

Unfortunately, Egypt still has widespread poverty, as most jobs in the informal sector are low-paying and often well below the minimum wage. The national poverty rate in Egypt recently went down just before the pandemic from 32.5 percent in 2017/2018 to 29.7 percent in 2019/2020; however, the pandemic is expected to exacerbate poverty once more.

Egypt’s national poverty line is set at EGP 857 per month, which is around EGP 28.5 and $1.82 per day. However, when adjusted for purchasing power parity, Egypt’s national poverty rate exhibits a similar rate to the World Bank’s designation of the lower-middle income poverty line of $3.20 (2011 PPP).

As can be seen by the graph below, 3.2 percent of Egypt’s population was below the international extreme poverty line at $1.90 (2011 PPP). However, that still means that over three million people are in extreme poverty. A World Bank report puts Egypt’s multidimensional poverty rate at 4.1 percent of the population, which the report notes is comparatively low. However, by lower-middle income, let alone upper-middle income country standards, poverty is still widespread at 28.9 and 72.6 percent respectively, according to the latest World Bank data.

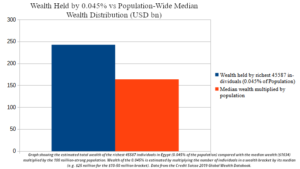

There are yet questions to be asked when it comes to Egypt’s socioeconomic conditions and how to address the longstanding issues of poverty, inequality, and inadequate service delivery, especially in the areas of health and education. There has been some progress in this regard, with attempts to modernize the education system and gradually move toward universal health coverage. However, the question of income and wealth inequality still lingers. According to estimates in the Credit Suisse 2019 Global Wealth Databook, wealth concentrated in the hands of the country’s richest 45000 individuals, less than 0.05 percent of the population, is more than the median wealth distributed to the entire population, as illustrated below. Although subsidies have been cut (and many such as fuel rightly so), economic benefits have failed to “trickle down.” Social protection efforts provided during the pandemic are a good start, however, and one can only hope that going forward the structural reforms are pursued not just in a macroeconomic sense but in a socioeconomic one as well, ensuring that the benefits of Egypt’s revitalized economy are distributed in a more equitable way.

Egypt has the potential to become a regional economic leader and global powerhouse. What is needed is a clear economic vision and the will to execute it. In 1991, and again in 2016, Egypt subscribed to the IMF’s economic vision of structural reforms (with no small degree of austerity), that forced it to push for an empowered private sector and a dynamic and resilient economy. This economic resilience proved its worth throughout the Covid crisis. However, questions remain regarding how systematic these structural reforms have been, how empowered the private sector actually is, how equity-driven Egypt’s socioeconomic landscape is, and whether the Egyptian economy is heading toward fulfilling its full potential. Bakhache believes that excellent progress has been made, but work still needs to be done, especially when it comes to exports and investments. To imagine if the pandemic had hit Egypt five years earlier, in 2015 rather than 2020, is a worrisome thought.

Omar Auf is deputy senior editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. He has previously worked and published in independent media organization Mada Masr and as an assistant editor at the Cairo Review.

Auf holds a Master of Global Affairs degree with a regional and international security concentration from the American University in Cairo, and a Bachelor of Arts in economics from Sciences Po Paris.

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter