Modi’s Bold New World

Narendra Modi was a global pariah only a few years ago, a Hindu nationalist vilified for anti-Muslim riots that left hundreds dead in Gujarat state. Halfway into his term as India’s prime minister, his swashbuckling foreign policy is scoring military and economic deals from Washington to Beijing.

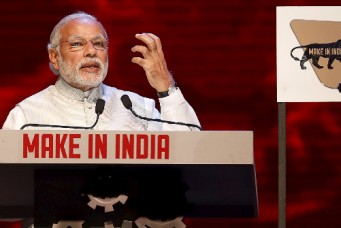

Modi at the Parliament House, New Delhi, Jan. 31, 2017. Adnan Abidi/Reuters

In early March 2013, following pressure from students and professors, the University of Pennsylvania cancelled a lecture that Narendra Modi, then the chief minister of India’s Gujarat state, was scheduled to deliver via videoconference later in the month. At the time, Modi was dogged by allegations that he had failed to stop anti-Muslim riots that killed over one thousand people in Gujarat in 2002. As a result, he had effectively been banned from the West. The United States, citing an obscure law that prevents foreign officials guilty of egregious religious freedom violations from entering the country, had rejected his application for a visa in 2005. The European Union had also refused to let him visit.

Times certainly have changed. As prime minister, Modi is taking the West—and the world—by storm. He hobnobs with heads of state and holds forth with the world’s top corporate leaders. He draws capacity crowds to celebrity venues like New York’s Madison Square Garden and London’s Wembley Arena. In 2014, he even shared a stage with Beyoncé and Jay Z at the anti-poverty Global Citizen Festival in Central Park. Such is the world’s adulation for Modi that relatively few overseas observers—other than human rights and religious freedom activists—have called out the Hindu nationalist leader for his draconian policies at home, which have included crackdowns on nongovernment organizations that receive foreign funding.

The transformation from pariah to pop star since Modi became prime minister in 2014 is nothing short of extraordinary. And yet it’s not just a story about the remarkable rehabilitation of a politician’s reputation—it’s also a broader tale about India. New Delhi’s foreign policy has become increasingly personalized by its globetrotting, spotlight-seeking prime minister. This was most certainly not the case with Modi’s predecessor, the bookish and camera-shy Manmohan Singh.

Modi’s deep personal imprint on India’s foreign relations helps drive a foreign policy focused around three broad themes: prosperity, national interests, and recognition as a global power. The prime minister highlighted the importance of each of these in a speech to a geopolitical conference held in New Delhi in early 2017, emphasizing in particular that the world should welcome India’s growing clout. “Our economic and political rise represents a regional and global opportunity of great significance,” he declared. “It is a force for peace, a factor for stability, and an engine for regional and global prosperity.”

Observers should not dismiss Modi for reveling in swashbuckling personal diplomacy. On the contrary, he appreciates the strategic importance of intense personal interactions in international relations. “The world is interconnected and interdependent,” he said in a 2016 interview on the Indian TV news channel Times Now. “You will have to connect with everybody at the same time.” Not surprisingly, as of February 2017, Modi had made more than fifty foreign trips as prime minister.

Modi’s active personal diplomacy has produced a series of major deals that help serve Indian national interests and promote economic development. These include an accord for the United Arab Emirates to invest up to a whopping $75 billion in infrastructure, one of India’s key needs. The business community in India has cited poor or nonexistent infrastructure as its greatest hurdle, and Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has admitted that the country will need $1.5 trillion over the next decade to address its infrastructure gap.

Modi has also concluded a uranium deal with Australia to boost India’s lagging nuclear energy capacity. India is in great need of energy on the whole; economists have estimated that for Indian economic growth to register in the double digits, energy supplies must increase by three to four times over the next few decades—and yet India currently suffers from peak demand deficits in electricity that reach 25 percent in some regions. When the deal was announced in 2015, India’s nuclear energy capacity was under 5,000 megawatts—less than 2 percent of the country’s total power supply.

Additionally, Modi has signed a transport corridor deal with Iran and Afghanistan. This accord entails the development of a port in the Iranian city of Chabahar, new roads, and a railroad stretching north from Chabahar to the Afghan border. India’s neighboring nemesis Pakistan has long denied it transit rights—a reality that underscores the significance of this deal for New Delhi. A completed transport corridor with Iran and Afghanistan would give India direct land access to key markets—and energy resources—in Afghanistan and by extension in Central Asia for the first time since Partition in 1947.

Furthermore, after several years of unsuccessful negotiations, India was granted membership in the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), a prestigious thirty-five-member entity that facilitates New Delhi’s access to missile technology. Entry into the MTCR is particularly important for New Delhi given that rival Beijing has long wielded its veto to prevent India from joining the Nuclear Suppliers Group, another prestigious club that hastens access to critical technologies.

Arc of Ambition

At home, Modi projects himself as a determined, can-do reformer. This attitude is reflected in his foreign policy as well—evidenced not only by his ability to strike big-ticket deals, but also by his willingness to be bolder and less risk averse than his recent predecessors. Indeed, India’s foreign policy has become more ambitious under Modi, setting new precedents and going places it hasn’t gone before. This is well illustrated by three of Modi’s key policies: stronger engagement with East Asian neighbors, pushback against Pakistan, and deeper defense ties with the United States.

Modi first announced his “Act East” policy in 2014 at the annual summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). It replaces India’s former passive-sounding Look East policy and telegraphs New Delhi’s determination to more actively engage its Asian neighbors to the east. The basic parameters of Act East are the same. New Delhi has long appreciated the strategic necessity of engaging its east. A nation with great power aspirations, after all, needs to cultivate influence not only in far-flung regions, but also in areas close to home—particularly when this broader backyard boasts two-thirds of the world’s population and a major portion of its wealth.

However, three factors suggest that the Act East policy is more than what one critic has dismissed as a “catchy but vacuous” initiative. First, Modi has been extremely present in East Asia. As of February 2017, he had made fifteen visits to the region—more than twice as many as Singh had made at a similar point in his term. Second, Act East has produced some major agreements. One is the uranium deal with Australia. Another is an oil and defense accord with Vietnam that provides naval vessels to Hanoi and grants oil exploration rights to New Delhi in parts of the South China Sea. The deal is a potential boon for India’s energy security but also shows the extent of Modi’s readiness to reach eastward: under the deal, Indian interests (from its oil workers to possible energy assets) could be directly imperiled in the event that rising regional tensions over China’s claims in the South China Sea lead to conflict.

Finally, India’s implementation of the Act East policy has been accompanied by a strong embrace of the new and emerging economic architecture proliferating across the Asia Pacific. India is the second-largest shareholder in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. It is also one of sixteen nations—including China—negotiating the formation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This initiative, which is comprised entirely of Asian countries, has taken on new importance since President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Trump’s move effectively rendered that formerly U.S.-supported trade pact—one that India was never a part of—dead in the water. RCEP, if ratified, would make up a trade bloc comprising half the world’s population and almost 30 percent of global gross domestic product. Significantly, RCEP would further embed India in regional economic networks by facilitating access to key supply chains in Southeast Asia, which houses some of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Pushback against Pakistan is another feature of Modi’s bolder foreign policy. Since independence, the troubled India–Pakistan relationship has vacillated between periods of conflict and calm. During his first year and a half in power, Modi sought the latter. He extended an olive branch and pushed for dialogue. In late 2015, he even made a surprise visit to Pakistan to see his counterpart, Nawaz Sharif. However, in 2016, a year that featured two major terrorist attacks on the Indian military that New Delhi blamed on Pakistani militants with ties to Pakistan’s security establishment, Modi changed tack—in dramatic and arguably unprecedented fashion. He made bold statements that Indian leaders rarely make: he threatened to reexamine and even revoke the Indus Waters Treaty, a decades-old water-sharing agreement that ensures that the Indus River—a critical water source for Pakistanis—flows downstream unencumbered into Pakistan. In his annual independence day speech, he boldly expressed solidarity with people in Balochistan—an impoverished Pakistani province convulsed by a separatist insurgency that Islamabad accuses New Delhi of helping foment.

Modi announced in September 2016 that India had staged a limited military strike on Pakistani terrorist facilities along the disputed India–Pakistan border. India has carried out these covert crossborder strikes before, but rarely if ever has it gone public about them. The message was clear: Pakistan was being put on notice that India is willing to resort to punitive measures to safeguard its national security. New Delhi also announced a campaign to diplomatically isolate Pakistan until the latter cracks down on anti-India terrorists on its soil. The opening salvo was a successful effort to convince member states of the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation to boycott a summit meeting planned in Islamabad.

While Indian leaders have typically sought to avoid overly antagonizing Pakistan, Modi has taken a more defiant position that appears less concerned about Pakistani responses. Tellingly, in 2015, New Delhi signed off on a deal to transfer Russian-made fighter helicopters to Afghanistan—the first time India had sent offensive weaponry to Kabul. Previous Indian leaders have held off, in part to avoid provoking the ire of a Pakistani security establishment that resents any semblance of an Indian military footprint in Afghanistan. Modi, however, was not deterred.

Strengthening India’s military ties with Washington is another example of Modi’s bolder posture. U.S.–India relations have enjoyed growing momentum since the early 1990s. One constraint, however, has been India’s concerns about taking security cooperation too far, for fear of violating the nonalignment principle that has long guided Indian foreign policy and precluded New Delhi from pursuing alliance-like arrangements. India has gradually relaxed its embrace of nonalignment in recent decades, but under Modi this transition has seemingly accelerated. In late 2016, Washington and New Delhi agreed to a deal that gives the latter the status of “Major Defense Partner.” This means that in the realms of defense trade and defense technology sharing, Washington will extend to New Delhi the same types of benefits it does to America’s closest allies.

This isn’t to say the United States and India will be fighting wars together anytime soon; New Delhi isn’t yet ready to completely shake off the nonalignment albatross. Indeed, the mere suggestion—proposed by a top U.S. military commander in a New Delhi speech in 2016—of staging joint patrols in Asian waters prompted immediate rejections from India. Still, under Modi, Indian messaging on bilateral military cooperation has been notably robust. A 2014 joint statement issued after a summit between Modi and President Barack Obama underscored “the importance of safeguarding maritime security and ensuring freedom of navigation and over flight throughout the region, especially in the South China Sea”—suggesting the future prospect of some level of operational cooperation, including in conflict-prone regions.

Indeed, New Delhi’s rising concerns about Beijing’s increasingly provocative actions in the South China Sea, coupled with India’s growing presence in the Asia Pacific region thanks to its Act East policy, have likely influenced Modi’s decision to push for a stronger defense partnership with Washington, which in recent years has pushed for its own “pivot,” or “rebalance,” to East Asia. New Delhi’s interest in deepening naval engagement in Asia—spelled out in a revised maritime security strategy released in 2015—suggests that U.S.–India maritime cooperation could be a major focus area for U.S.–India defense relations.

Policy and Panache

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) 2014 election manifesto provides a strikingly accurate window into the current government’s thinking about foreign policy. It lays out what can perhaps be described as the makings of a Modi doctrine: the embrace of an active, confident, and tightly focused foreign policy that aims to better position India as a rising power and accelerate its path toward superpowerdom.

The manifesto, perhaps underscoring the importance of intensive international diplomacy, contends that India’s previous government “failed to establish enduring friendly and cooperative relations with India’s neighbors.” The document laments how India’s foreign policy has been marked by confusion rather than clarity, and that India has been “floundering” rather than “engaging the world with confidence.” The manifesto promises to build “a strong, self-reliant, and self-confident India, regaining its rightful place in the comity of nations.” The document’s foreign policy guiding principles state that “we will engage proactively on our own with countries in the neighborhood and beyond….We will pursue friendly relations. However, where required we will not hesitate from taking [a] strong stand and steps.” These principles are quite consistent with the moves Modi has pursued in office, such as the Act East strategy and the muscular policy toward Pakistan.

Several other core characteristics undergird India’s foreign policy. These include “enlightened self-interest”—a principle also championed by previous Indian governments, and which stipulates that India’s foreign policy should be carried out independently, without ideological influences or historical baggage. The noted Indian strategic analyst C. Raja Mohan argues in a book on Modi’s foreign policy that this tenet has been on full display—from the prime minister’s engagement with Washington despite the earlier U.S. visa ban to his desire to pursue a workable relationship with China, a nation that once fought a war against India and today is arguably New Delhi’s greatest strategic competitor.

Another core component of India’s current foreign policy is unpredictability. At first blush, this may seem counterintuitive, given New Delhi’s emphasis on a focused and disciplined foreign policy. In fact, however, it’s very much in line with the Modi government’s penchant for bold moves. Consider Modi’s surprise visit to Pakistan in 2015; the unexpected visual of Modi, only three months into his term, happily sitting alongside Xi Jinping, president of rival China, on a swing along a riverbank in Gujarat; and Modi’s invitation to Obama—issued just weeks after he met the U.S. leader for the first time, in Washington, in September 2014—to serve as chief guest at India’s Republic Day festivities the following January. This marked the first time an American president was invited to receive this prestigious honor.

There is actually a fair amount of continuity, too, in Modi’s foreign relations. This includes maintaining strong relations with New Delhi’s old Cold War friend Russia; pursuing a strong economic partnership with Beijing despite ample political tensions; undertaking energy-focused diplomacy in the Middle East; and engaging global forums like BRICS. Additionally, India’s often obstructionist position in global trade negotiations has persisted (in fact, rumors—rejected by New Delhi—abounded in 2016 that India’s overly protectionist position threatened to get it kicked out of RCEP negotiations ). To its credit, however, the Modi government has taken a more conciliatory position in international negotiations over climate change than did its predecessor.

For all of Modi’s foreign policy success stories, he has fallen short on several fronts. India’s hopes to make more of a splash on the global stage have been dashed to some degree by its continued inability to gain entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group and to secure a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. Meanwhile, India’s efforts to patch up relations with its South Asian neighbors (setting aside Pakistan) have suffered a blow thanks to a major spat with Kathmandu, which accused New Delhi of indirectly supporting a blockade of goods into Nepal along the India–Nepal border for several months in 2015 and 2016. Some Indian commentators have also accused New Delhi of aggravating its relations with Pakistan by botching its policy in the disputed region of Kashmir. New Delhi antagonizes Islamabad, contend these critics, by constantly blaming Pakistan for recent unrest in Kashmir without acknowledging that India’s own policies, and particularly its heavy-handed security measures in Kashmir, are a big part of the problem.

Modi’s foreign policy could face additional challenges—both externally and internally driven. Global geopolitics have changed dramatically since Modi assumed office—a reality that could have deleterious impacts on New Delhi’s foreign relations. The Trump administration’s pledge to leave a lighter footprint in the world, and its threat to revisit its relationships with longstanding alliance partners in Asia, raise the specter of stepped-down U.S. engagement in Asia—and perhaps even an end to America’s rebalance policy. A less present America in Asia would constrain the regional security cooperation that New Delhi hopes to scale up with Washington. A downscaling of America in Asia would also strengthen China in a big way, adding to Beijing’s already-formidable clout in the Asia Pacific and complicating Indian efforts to shore up its own influence in the region.

Internally, India’s foreign policy could be hampered by an age-old problem: insufficient capacity within foreign policy institutions. This ranges from a lack of people working in the foreign policy establishment to the absence of an institutionalized process of policy planning and policymaking within the Indian foreign ministry. When India’s foreign secretary asked senior officials who within the government does the thinking about overall foreign policy, “he was met with embarrassed silence,” according to a Brookings Institution study of Modi’s foreign policy. Efforts are underway to address these institutional constraints, but these are longstanding challenges, and even a can-do type like Modi will have his work cut out for him.

With Modi now well into the second half of his five-year term, his popularity abroad remains high and his personal diplomacy robust—even as his government has begun to wholeheartedly embrace a Hindu nationalist social agenda at home. In March, it appointed a hardline, anti-Muslim monk to serve as chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state. There’s no reason to doubt that the he will continue to travel the world with panache, wage an energetic foreign policy, and garner many happy returns for his country’s economy, national interests, and global reputation.

Michael Kugelman is the deputy director of the Asia Program and senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He is a regular contributor to Foreign Policy and has written for the New York Times and Washington Post. On Twitter: @MichaelKugelman.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter