Egypt’s Search for Truth

The effort to hold the former regime of President Hosni Mubarak to account is off to a poor start. But as the experiences of other nations in transition have shown, establishing a credible record of past abuses is essential to forming a democratic culture.

Protesters holding up posters depicting Khaled Said, an Egyptian man killed in police custody, Alexandria, Sept. 25, 2010. Tarek Fawzy/Associated Press

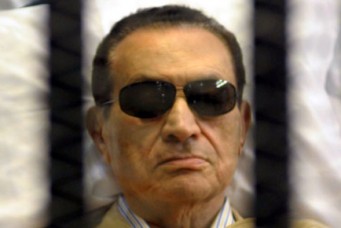

When the deposed former president Hosni Mubarak was wheeled on a hospital bed into the makeshift Cairo courtroom hastily prepared for his trial, the process of transitional justice in Egypt appeared to have achieved an important symbolic victory. The sight of the former autocrat laid low before a court of law to be held accountable for his actions was undoubtedly an important marker of the fundamental changes that have convulsed Egypt following its eighteen-day uprising and the fall of the Mubarak regime. After numerous court proceedings against former Mubarak advisors and confidants, the start of the trial also appeared to fulfill a central demand of the uprising: that Mubarak and his cronies face justice for their past crimes. Yet, the outsized focus on the former president and the speed with which his trial was initiated also raised troubling questions about the future scope and trajectory of transitional justice efforts, converging with broader worries about the course of Egypt’s transition.

[youtube video=https://youtu.be/RUP3hzWDc2M class=vids]Much like the muddled political transition overseen by Egypt’s Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), transitional justice has been characterized by ad hoc decision-making and suffered from a fundamental lack of transparency and popular participation. The outcome of Egypt’s extended struggle for political supremacy—parliamentary elections are due to take place in November 2011 and presidential balloting at a date still to be determined—will shape the depth and scope of transitional justice efforts. Based on the reactionary posture of the SCAF during its tenure as Egypt’s ruling authority, it is a near certainty that transitional justice efforts will remain rudimentary until such time as civilian authority is reinstated. The transition to civilian authority will provide an opportunity to revisit those areas that have been neglected during SCAF’s control. Renewed focus on justice, accountability, and equality before the law would also provide a significant link to the ethos that animated Egypt’s unexpected uprising and direct attention to those lofty goals at a time when prosaic and flawed politics are becoming the central focus of the country’s attention.

Transitional justice will be highly contested within Egyptian society. The goals of these efforts are not simply retributive, although punishment and deterrence through prosecutorial action are certainly important results. Addressing the claims of the former regime’s victims would help in establishing a credible basis for political reconciliation. The creation of an unimpeachable historical record of the excesses and abuses of the Mubarak regime would play a significant role in the difficult long-term task of forming an open and accountable political culture.

The normative value of transitional justice efforts would also have political utility if implemented judiciously, as efforts at increasing accountability for past regime crimes would be an important route to ensuring the supremacy of civilian governance and bolstering the country’s democratic infrastructure. This type of initiative could also play an important part in nurturing judicial independence as a check against future official abuse.

The Egyptian military would likely be much more comfortable with a discrete focus on the excesses of Egypt’s crony-capitalist economy and the violence associated with the repression of the January 25 uprising. The military has played a less pronounced political role in recent years, but a more probing initiative that sought to speak to the systematic crimes of the former regime and its predecessors would more directly implicate the military in light of its central role within Egypt’s authoritarian superstructure. This is particularly the case for earlier periods when Egypt could be described as a military state and society, and the military and its officer corps were implicated directly in day-to-day repression. As such, the military would be averse to broader efforts seeking to document state repression during the time of Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat, in addition to the years of Mubarak’s rule. Demonstrating credibly the repression that has characterized the Egyptian state since the Free Officers’ Movement and the toppling of King Farouk in 1952, however, would have the benefits of reinforcing the imperative to break with the past and lending legitimacy to civilian efforts to limit military interference in governance.

Conversely, an aborted or truncated transitional justice process would likely have deleterious effects on Egyptian society and would divert the search for truth to unfortunate ends. Association with the former regime would provide fodder for the politics of demagoguery and character assassination, with no recourse to institutional checks or burden of proof. The questions that animate transitional justice efforts will not be resolved in the short term. Decisions in the coming months will perhaps complicate future options but will not necessarily foreclose all of them completely. The complex process that undergirds the push for truth and accountability will undoubtedly evolve over time. The struggle to define earlier eras will play a key part in the country’s political discourse, and it is likely that transitional justice efforts will mirror Egypt’s future political, social, and cultural evolution.

From Nuremberg to South Africa

The widely varying responses of countries to the past and issues of accountability indicate that there is no agreed-upon set of prescribed approaches to transitional justice. National responses are an outgrowth of the particular circumstances of a country undergoing a transitional juncture. Yet, accumulated practice offers insights into the various modalities that may be employed in the pursuit of accountability and the many difficulties that states may encounter. This practice has also illustrated that these modalities are often interlinked and overlapping, supporting a broad and flexible discourse.

Traditionally, the quality of transitional justice has been governed by both the extent of governmental change and the political will to tackle wrenching questions that implicate large swaths of a society. In this sense, outright victory, in terms of war, or regime change, have, historically, provided a clearer path to serious engagement with transitional justice processes. Such situations have at times led to excesses and accusations of revenge, retribution, and victor’s justice. The ability to balance the need for accountability with the imperatives of reconciliation and social cohesion has often been lost as a result.

The discipline that has come to be known as transitional or post-conflict justice took more cohesive form in the 1980s and 1990s following a series of high-profile engagements with this set of issues. In many instances, the efforts to account for the past have not simply been a function of transitional politics and finite timelines, and the term itself does not convey fully how these issues can play out within societies for years and decades. In this sense, transitional justice is not a “now or never” proposition, although certain approaches reliant on testimonies and the safeguarding of data may not be delayed to a more conducive moment.

With the landmark initiation of a truth and reconciliation process in South Africa and the institution of ad hoc international tribunals to address the atrocities in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, transitional justice garnered significant international support and academic focus. During this period, a tentative consensus began to coalesce on the need for engagement with the crimes of the past as a necessary prerequisite for the creation of an open and responsive democratic political order and culture. There also emerged an understanding that stabilization and security were often enhanced by ending impunity and limiting the possibilities for unsanctioned revenge, thereby creating a basis upon which societal divides could be overcome.

These developments were a necessary antidote to the practice of political expediency that purported to prioritize stability and, for far too long, inhibited a proper accounting of past misdeeds. In addressing Chile’s long-running failure to prosecute past human rights violations, Jorge Correa Sutil, the former deputy minister of interior in Chile and a judge in the Chilean constitutional court, noted that societal ambivalence was a reflection of “continuing concern among many . . . that any solution that is found to the human rights issue will, in turn, obstruct other political and economic objectives.” Legitimate concerns about social cohesion endure and should be heeded in mapping appropriate and properly-tailored transitional justice strategies, and recent experience offers lessons as to the often difficult balance between stability and justice. On occasion, such lessons have been cautionary, as when zealotry and vengeance have replaced rational analysis in determining the scope and impact of transitional justice processes. Without heed to the practical and political constraints governing its application, transitional justice can be a destabilizing factor. As the noted journalist Tina Rosenberg has observed in her 1995 book, The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism, “Justice must be done—but too much justice is also injustice.” In the aftermath of wholesale regime change or total military victory, it is often the very circumstances that have enabled transitional justice efforts that have undermined their judicious application.

Despite tangible achievements, it is also clear from recent history that combating impunity and seeking accountability remain difficult and controversial endeavors. In this regard, according to the legal scholars George P. Fletcher and Jens David Ohlin, “even the most democratic and legally sophisticated countries may have difficulty punishing their own.” In the case of fragile transitional contexts, partisans of an ousted repressive regime, some of whom might retain an ongoing role in a successor government, will as a matter of course attempt to thwart efforts at establishing accountability.

Although the various strands of transitional justice have received greater systematic attention in recent decades, the antecedents to more robust conceptions of transitional justice can be found in the collective experience born of grappling with the atrocities of World War II. Particularly at the prosecutorial level, these crimes spurred disparate efforts to bring some number of perpetrators and collaborators to justice. While the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg has garnered disproportionate attention due its ambitious agenda and dramatic courtroom clashes, the vast majority of prosecutions undertaken against Nazi crimes and atrocities have taken place in domestic settings, including Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Croatia, Lithuania, Canada, and the United States. While the scope and adequacy of such prosecutions was inconsistent, these prosecutions at the national level constituted the few vital examples of transitional justice during the fraught Cold War era, during which time the development of transitional justice was largely stunted.

The so-called third wave of democratization, which began in the late twentieth century, and whose initial track record was undoubtedly uneven, set in motion a number of democratic transitions in which the issue of accountability was contested as part of the broader political struggles of that era. The turbulent and protracted transitions from military dictatorships to democratic governments in Latin American are particularly relevant with respect to Egypt’s transition. Country-level responses varied dramatically based on the relative continuing power of the militaries and their ability to thwart civilian and judicial efforts to initiate transitional justice processes, ranging from prosecutions of high-level perpetrators, historical commissions, and vetting. However, the breadth and diversity of experience in the Latin American context has now been integrated into the political imagination of the region and created shared understandings and expectations.

But even efforts that failed to immediately achieve stated goals had an ameliorative effect on the long-term struggle to break with the past. Following its transition to civilian authority in 1983 in the wake of its “Dirty War” and the disappearance of at least 14,000 under the rule of a military junta, Argentina began efforts to reconcile with the brutality of its recent history. Central among those efforts was an attempt to prosecute the nine leaders of the military junta. The prosecutions resulted in five convictions, but also set in motion a furious counterreaction that truncated those efforts and led to the passage of amnesty laws and pardons. The issue remained vital within Argentine society due to the persistence of civil society groups and was resuscitated in 2005 when the Argentine Supreme Court declared the country’s amnesty laws unconstitutional.

Undoubtedly, the Argentine experience demonstrates the depth of resistance launched by members and partisans of the former regime. However, even in the face of manifest reversals, it also demonstrates the importance of the efforts to keep issues of accountability alive and the influence such efforts can have on the establishment of new social norms. This type of dual utility is indicative of the potential role of prosecutorial strategies, even when initially unsuccessful, in the reconstruction of political culture and the establishment of democratic institutions.

Prosecutions alone, however, are an inadequate tool. The inherent practical limitations attendant to judicial processes mean that only a select number of perpetrators can be prosecuted. To fill such gaps, states have increasingly relied upon vetting to bar individuals responsible for past abuses from participation in government and political life. Such bars may vary from lifetime bans to limited periods of disqualification. Vetting is a clear method for instilling popular confidence in a country’s newly formed democratic institutions. It is also reasonable to assume that old power structures, particularly in rural settings, may prove resilient and immune to change.

While vetting is a critical facet of any comprehensive approach to transitional justice, its application is prone to excess. States tend to employ less rigorous modes of adjudication because the sanction is less onerous than a criminal finding even if it remains significant. The political ramifications of vetting may be great, often encouraging strategic exploitation for political ends.

Vetting processes were employed, although haphazardly, following the end of World War II, with denazification being the best known of these experiences. In addition to the post-World War II examples, transitioning societies in Latin America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East have undertaken vetting efforts, with widely differing degrees of sincerity and success. Two of the more recent experiences with vetting, in post-Communist Czechoslovakia and post-Baathist Iraq, offer cautionary tales as to the potential for overreaching in design and implementation.

The need for lustrace, or lustration, the vetting process undertaken in Czechoslovakia, was acute and the transition process faced real dangers from elements of the former regime and its collaborators. Although many came to see the Czechoslovakia experience as a witch hunt, “the witches were real,” in the words of Tina Rosenberg. Among the controversies created by its broad lustration process was the evidentiary challenges created by reliance on the files of the secret police, the Státní Bezpečnost, or StB, for proof of collaboration. This system resulted in numerous errors since such files are often inaccurate and open to fabrication. Fabrications were often a function of the need of security service personnel to reach certain quotas for compensatory reasons, and at such times were not reflective of actual collaboration. Similarly, such files were also fabricated to be used as leverage to pressure collaboration through the threat of release of incriminating but falsified evidence. Such standards also do not account for actual behavior, as mere inclusion does not indicate the nature of the contact or necessarily equate with treachery or outright collaboration. Finally, reliance on such files produced a distorted picture since files were subject to manipulation and destruction, often leading to the exclusion of senior leaders. The experience suggests strongly that with respect to secret collaborators, due process protections and stringent evidentiary requirements are essential and that the focus must be on actual behavior as opposed to mere association.

Iraq’s more recent experience with vetting through de-Baathification also proved problematic, particularly with respect to over-broad formulations that focus on mere association as opposed to actions. The Iraqi precedent has now come to be seen as a warning, and transitions in the Arab world have, for the moment, focused on the excesses of the Iraqi example and its destabilizing effects. De-Baathification crippled Iraq’s administrative services and bureaucracy and purged lower-ranking members of the Baath party who had joined merely to advance their careers or secure employment. The policy was initially implemented by the Coalition Provisional Authority, as the temporary occupying power, but was zealously overseen by the country’s de-Baathification commission and its first head, the controversial exile politician Ahmed Chalabi. The initial scope of the vetting process included the dismissal from all government service of the four top levels of Baath party membership and instituted lifetime bans on future participation. This approach was focused solely on association and rank and did not rely on any evidence or findings of wrongdoing, although exceptions could be granted on an individual basis. Many observers believe that by negatively affecting Sunni Muslims who formed the base of Saddam Hussein’s support, de-Baathification exacerbated sectarian divisions and fueled a Sunni insurgency. While the excesses of de-Baathification led to a reassessment of Iraq’s vetting policies and a revised legislative approach, the sectarian and political divisions of the country thwarted implementation.

Despite these unsuccessful efforts to curb the scope of the policy, de-Baathification remained a potent political weapon. It was resurrected recklessly during preparations for the country’s March 2010 parliamentary elections to polarize electoral discourse on sectarian lines, stunt cross-sectarian politics, and exclude political actors without adequate process. The Iraqi experience is a testament to the necessity of standards of proof and guarantees of due process. The associational aspects of the approach have hindered meaningful political reconciliation and stigmatized large classes of people while also empowering demagoguery and amplifying sectarian trends.

Beyond the need for dealing with members of the former regime, truth commissions and other investigatory bodies have come to be seen as important transitional justice mechanisms. While the practice of establishing investigative bodies is not a recent phenomenon, its profile grew with the establishment of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). In fact, such bodies had been widespread throughout Central and South America from the early 1980s, although with varying degrees of efficacy.

Unfortunately, some of the attention on truth commissions is partly due to resistance to prosecutorial strategies and an impression that such investigatory methods offer a less divisive route to truth-telling. However, South Africa’s TRC was unique due to the broad powers conferred upon the body, such as subpoena powers and the ability to grant amnesties under certain circumstances. These powers allowed the TRC to go beyond the mere construction of historical narrative, but amnesties proved to be a controversial approach to eliciting confessions. The public nature of proceedings was constructed as a means toward accountability, by forcing those offering testimony in return for amnesty to do so publicly.

The work of the TRC met with mixed reaction in South Africa as it proceeded, but by its completion many had come to appreciate its role in cultivating a sense of national unity. The TRC’s approach also demonstrated the utility of conditioned and limited amnesties, in distinction to the problematic use of blanket amnesties. Particularly with respect to low-level perpetrators, such amnesties can be a recognition of the scarcity of judicial resources and a possible route to breaking down the conspiracy of silence surrounding the security sector and its repressive apparatus. These positive attributes, however, should not be cause for displacing or preempting other transitional justice strategies. However, cumulative practice in varied national contexts offers strong support for the establishment of truth-telling bodies.

An often overlooked aspect of transitional justice is the attitude of the successor state as expressed through educational reform and symbolic actions such as apologies and practices of memorialization. Such steps, in other contexts, have blunted the impulse for revenge and provided a basis upon which political reconciliation could move forward.

Finally, and more recently, state practice has begun to reflect the emerging academic consensus regarding victims’ rights and reparations. While the examples in practice are limited, a variety of approaches have been implemented, including restitution, compensation, and rehabilitation. While these measures cannot be restorative, they are a reflection of a political commitment to the victims of the former regime and provide a basis for their reintegration into society.

Egypt in Transition

Egypt poses a unique set of challenges due to the particular circumstances that ushered in its transition. As opposed to outright revolution and toppling of the political order, the uprising in Egypt and the removal of the former president required the intervention of the armed forces, themselves a key pillar of the former regime. However, while the Egyptian military had once dominated all facets of government, its role in politics and governance had diminished in recent decades. The military enjoyed distinct privileges, but the Egypt of the Mubarak era could no longer be described as an outright military regime and witnessed the emergence of competing centers of authority, such as the Ministry of the Interior and the crony-capitalist elite associated with the president’s son, Gamal Mubarak. Further, the armed forces were insulated from the practice of day-to-day repression. This allowed the Egyptian military to untether its own future from the fate of the president and his inner circle of civilian advisors.

The transitional government, overseen by the SCAF, has initiated a series of circumscribed steps to address both the corruption that typified the Mubarak regime and the violence directed at protesters during the eighteen-day uprising. The process, in keeping with the SCAF’s approach to the overall transition, has been opaque and haphazard. Furthermore, the interim government’s commitment to accountability has appeared to fluctuate in relation to the level of public outrage and protest, and lacked an articulated rationale for its course. There has also been insufficient public discussion of the direction of transitional justice efforts and this has fueled popular frustration and suspicion regarding the SCAF’s intent. It has also led to public cries that justice must be meted out swiftly, which has complicated efforts to ensure due process to the accused and undermined proper investigatory and prosecutorial processes. Such uncertainties have been compounded by the routine use of military courts for civilians, which became a standard practice for the SCAF. The summary and swift fashion of these military court decisions, alongside the continuation and expansion of the emergency law, has stood in stark contrast to the inconsistent course of accountability efforts for the former regime.

The early moves to prosecute the associates of Gamal Mubarak, such as Ahmed Ezz, the steel magnate and former leading figure in the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), are unsurprising in light of the military’s traditional antipathy for the neoliberal elite cultivated by the former president’s son and the broad public disgust with official corruption. The series of corruption cases involving former high-level members of the Mubarak government, such as Youssef Boutros-Ghali, the former minister of finance, Rashid Mohammed Rashid, the former minister of trade and industry, and Anas Al-Fiqqi, the former minister of information, have proceeded at speed and have raised the specter of inadequate process, although these trials have met with public approval.

Similarly, there has been broad public support for the efforts to prosecute those responsible for the violent crackdown on protesters during the January 25 uprising. The decision to prosecute Habib Al-Adly, the reviled former minister of interior, was one of the first concrete signs that accountability for the crackdown would be pursued. The complicated and strained relationship between the military and the Ministry of the Interior, and the universal public scorn for Al-Adly, made this decision easier for the judiciary and the transitional authorities.

The fate of the former president, however, has been controversial. Some segments of society have viewed the trial as a national humiliation, given the former president’s role as a symbol of the state. The SCAF appeared to hesitate to go forward with Mubarak’s prosecution considering his military background and longstanding ties to the current leaders of the military. The decision to proceed with the prosecution appeared to be a key victory of the protest movement.

Subsequent events eroded confidence in the integrity of the proceedings, however. The preexisting suspicions of the military’s intentions were revived by the apparently inconsistent testimony given by the head of the SCAF and longtime minister of defense, Field Marshall Mohammed Hussein Tantawi. In leaks of his alleged secret testimony before the court, Tantawi is reported to have denied receiving orders to shoot on protesters, stating “We were not ordered to open fire at citizens and we will never do that.” In earlier public comments in May 2011 at a police cadet graduation ceremony, Tantawi had intimated that the military had refused such orders, stating, somewhat cryptically “We don’t open fire on the people.” This sentiment was further memorialized in the SCAF’s Communiqué No. 52. This apparent reversal raises the possibility that the SCAF’s acquiescence to the prosecution was merely an attempt to dampen the continuing protest movement and blunt far-reaching calls for systematic reform.

More generally, inconsistencies have bedeviled the prosecutorial track and the selection of appropriate cases. With very few other ongoing prosecutions, new developments have taken on greater import. In July 2011, riots erupted in Suez when seven policemen accused of killing seventeen protesters were released on bail. Reports indicate that one hundred and forty police officers are in various stages of prosecution for their actions during the uprising.

Ominously, the SCAF’s tenure has produced its own set of abuses as political repression has increasingly come to typify the transitional period. The broad public has partly been shielded from these abuses due to continuing state propaganda efforts and outsized confidence in the armed forces. With the shocking and brazen attacks on largely Coptic Christian protesters on October 9, which resulted in at least twenty-seven deaths at the hands of military, police, and vigilante forces, public discussion at an elite level has shifted, and calls for accountability among a small segment of society have now begun to encompass the transitional period. All told, the situation lacks clarity as to the intent, progress, or scope of current investigations.

In addition to prosecutions, the transitional government established a commission of inquiry in order to investigate the repression and violence employed by the former regime during the January 25 uprising. The fact-finding commission concluded that at least 825 protesters were killed and over six thousand injured during the uprising and that the police forces were responsible for many of those deaths. Among the commission’s key findings was the use of snipers by the Ministry of the Interior. As opposed to injuries and deaths resulting from clashes between protesters and security forces, the use of snipers is unambiguously indicative of premeditated plans to kill and injure protesters. As such, this issue continues to prove contentious, with Ministry of the Interior officials denying the use of snipers during the eighteen-day uprising and, in some statements, denying that the ministry employed snipers at all. The commission also implicated NDP figures with orchestrating violence against protesters, including the February 2 attack on Tahrir Square when armed thugs descended on protesters on camel and horseback. In addition to its limited scope, the work of the commission has not been highlighted by the transitional government or accompanied by public outreach, undermining the usefulness of the exercise and its impact.

The SCAF also established a compensation fund for victims of state repression during the uprising. The fund began disbursements during the month of Ramadan, with payments of thirty thousand Egyptian pounds ($5,000) for the families of those killed, fifteen thousand pounds ($2,500) for disabled protesters, and five thousand pounds ($833) for all others injured.

With respect to broader examinations of the former regime’s repressive past, prosecutorial efforts have been limited, exposing a clear gap in the current approach to accountability. In this regard, the case of Khaled Said, the Alexandrian whose June 2010 death as a result of torture helped galvanize the protest movement, was perhaps the only current instance of a criminal justice process looking beyond the eighteen-day uprising at the repressive legacy of the former regime. While rumors circulated as to the former interior minister’s complicity in an Alexandria church bombing in January 2011, no evidence has been presented to buttress these allegations.

Woefully incomplete efforts at security sector reform have also contributed to a sense of drift from the original goals of Egypt’s uprising. Thoroughgoing reorganization of the Ministry of the Interior and reconstruction of its prevailing culture is one of the more critical tasks for the transitional authorities and their successors. Reforms to date have been largely cosmetic. While the State Security Investigations unit (Mabahith Amn al-Dawla), the most feared arm of the ministry, has been disbanded, the jurisdiction and authority of its successor, the National Security Apparatus (Jihaz al-Amn al-Watani), remains undefined. The Central Security Forces (Amn al-Markazi) have also been involved in heavy-handed dispersals of peaceful protests, evoking their role under Mubarak in suppressing organized dissent. There is as yet no systematic vetting procedure for the ministry, and civilian oversight of its activities is weak. While the ministry announced the dismissal of several hundred senior officers in July 2011, the lack of transparency surrounding the move prompted skepticism regarding implementation. The endemic problems of the ministry will persist without a more consistent effort at inculcating respect for the rule of law and reforming the educational regimen for police officers.

Finally, limited steps have been taken to deal with the former ruling party, which was dissolved in April 2011 by court order and had its assets seized by the state, fulfilling a core demand of the protest movement. However, no plans for vetting former NDP members have been agreed to, and concerns remain about their ability to exploit their previous connections and organizational capacity for electoral gain and to thwart genuine efforts at systemic reform.

Imperatives of Accountability and Justice

With Egypt’s politics in flux, a return to authoritarianism is among the possibilities for the country. Grappling with the past is as much, in this regard, about preventing the return of dictatorship as it is about ending impunity. While an excessive preoccupation with justice and accountability could distort the focus of transition, without a proper and unimpeachable accounting of repression and authoritarian rule, the process of constructing a democratic culture and respect for the rule of law will be compromised from its inception.

The near-exclusive prosecutorial focus on corruption and the repression during the uprising raises an overarching question regarding the extent of commitment to fundamental reform and change. The necessary accounting facing Egypt is not solely bound up with the repression of the eighteen-day uprising or the financial crimes and corruption popularly associated with Gamal Mubarak and his associates. Instead, what is required is a probing of Egypt’s recent history, perhaps dating as far back as 1952 and the establishment of Nasser’s military regime.

The Nasser regime and its successors corrupted Egypt’s political life and inculcated a culture of impunity, constructing an unresponsive government and devaluing the dignity of Egyptians. The authoritarian order was assured by the repression of dissent, often through torture, arbitrary detention, and control of the media. These characteristics were not simply a reflection of the latter years of Mubarak’s rule, but represented a tradition of dictatorship that gave shape to Egypt’s national politics stretching back to the Free Officers’ Movement. The Mubarak regime tolerated a controlled level of dissent and its repression was not totalitarian in its application. However, the state was in the end still the arbiter of acceptable discourse and policed the boundaries. Serious political challenges were dealt with severely, even in their nascent stages. Further, apart from political repression, the routine interactions between citizen and state were often marked by heavy-handed brutality as a matter of course.

The experiences of other similarly situated societies suggest quite clearly that the success and efficacy of transitional justice is often a function of the breadth of those efforts chosen to address the past, bearing in mind that any such efforts will evolve over time. The scope of any such efforts is also reflective of a state’s commitment to the goals of transitional justice, as opposed to the cynical employment of transitional justice to further narrow political goals or to simply exact revenge against enemies.

Retribution is a reasonable goal for transitional justice, as it is for any criminal justice mechanism. However, prosecutions as a tool for accountability must necessarily be selective as a result of limitations of capacity and the serious burdens presented by thorough and fair investigations and trials. Bearing these limitations in mind, prosecutions must prioritize high-level actors in positions of responsibility and authority. The circumstances surrounding the violent crackdown against the largely peaceful protesters of the January 25 uprising will undoubtedly occupy future efforts and will be an area that captures the popular imagination.

However, discretion should be exercised in this regard, and aside from central regime decision-makers, prosecutions should focus on the most egregious incidents of unprovoked killing, with a special emphasis on the use of snipers against peaceful protesters. This should stand in distinction to those protesters killed during attempts to storm police stations and other government buildings, such as the Ministry of the Interior. Despite the moral claim that such actions were justifiable within the context of a revolutionary moment, as a legal matter it is difficult to imagine that defensive actions of individual police officers could be construed as unwarranted killings. Much like the dilemma faced by post-unification German courts during the trials of the East German border guards, while morally reprehensible, such actions were not technically criminal at the time of commission and, in the Egyptian context, could also be plausibly portrayed as self-defense.

Prosecutors should also engage in greater public outreach to reassure the public that credible investigations are being undertaken and that any judgments with respect to investigations and trials are solely a function of prosecutorial discretion. Transparency will engender public trust and afford investigators, prosecutors, and judges greater latitude to pursue their investigations without undue public pressure for speedy resolutions. Credible investigations and proper judicial function are not amenable to popular whims and temporal demands, and judicial authorities should be shielded from unreasonable pressures.

The focus of prosecutions must move beyond the events of the eighteen-day uprising, and prosecutors should look to the systematic abuses that characterized the repression of the former regime. In this regard, prosecutions could be a vehicle for elucidating the regime’s mechanisms of repression, including systematic use of torture and the corruption of the criminal justice system. This pattern of repression and abuse could arguably sustain a conclusion that international crimes, namely crimes against humanity, have been committed. However, there exists no technical legal basis in Egyptian law to prosecute international crimes. Based on the principles of legality, which require that public notice of a crime be delineated prior to the commission of a criminalized act, and the dualist nature of the Egyptian criminal justice system, prosecutions may only rely on domestic law as the basis for any future trials. Unfortunately, the lack of national-level incorporation of international crimes in the Egyptian criminal code has foreclosed the possibility of a symbolically powerful prosecution for a core international crime, such as crimes against humanity.

However, expanding the focus of prosecutions is crucially important to the long-term health of Egypt’s political culture. The legitimacy of the demands for change is not simply a byproduct of the brutal response to peaceful protest, but a rejection of decades of repression and authoritarian rule. Of course, the sheer volume and scope of such violations does not lend itself to vindication through judicial processes. Criminal trials are also insufficient in accounting for the many corrosive actions necessary to maintaining the regime that fall short of criminality. And it is here that Egypt will have to rely on other approaches to ascertain the full truth of the former regime’s crimes and repressive practices.

Among the options, a truth commission should be a component of Egypt’s transitional justice initiatives. A commission would have wide purview to provide an objective account of the decades-long history of violations and abuses. Judicious and regulated usage of amnesties for lower-level perpetrators could provide an avenue to exposing the excesses of the internal security apparatus, and bolster efforts at serious security sector reform.

Egypt will also have to be mindful of the victims of its authoritarian past. In this regard, victim-centered approaches should be crafted with an understanding that the state’s responsibility extends beyond the eighteen-day uprising to encompass those who have long suffered the caprice and cruelty of the former regime.

The issue of vetting has rightly received scrutiny, along with the fate of NDP-affiliated individuals. While vetting is a critical component of the transition the process, two options under consideration to bar the remnants of the former regime from participation in Egyptian political life were flawed and would have potentially negative ramifications if implemented. Unfortunately, the lack of proper preparatory work due to governmental indecision meant that the twin goals of fair process and sufficient scope could not be met.

The first such option is a blanket ban on all members of the NDP. Such a move would, in fact, be both over-broad and underinclusive. The NDP did not function as a true broad-based political party, though it sought to festoon its activities with the trappings of political party life, complete with platforms, policy documents, and secretariats. Political parties had been abolished in January 1953 following the Free Officers’ ascension to power, and the revolutionary regime had sought to fill this void with a regime-led political front, the Liberation Rally. The Liberation Rally was succeeded by the National Union, which included all Egyptians, and set the stage for political repression and the suppression of alternative modes of political organization. These political fronts were established primarily to thwart challenges from existing political culture, but neither played an active role in governance. These aborted attempts foreshadowed future regime efforts by both Nasser and Sadat to contain and direct Egyptian political life, although Sadat’s moves were often aimed at undermining the political forces loyal to Nasser. Within this stultifying political environment, Sadat introduced reforms aimed at establishing a controlled multiparty system, and it is within that context that the NDP was formed in 1978. In its later years, under the influence of Gamal Mubarak, the NDP sought to champion market reforms, but the party lacked coherence and broad-based participation. While the NDP dominated Egypt’s representative bodies, often through fraud and intimidation, it was, in many ways, simply a vehicle for patronage and electoral politicking.

Despite the fact that the numbers of those from the ranks of the NDP are relatively small, a blanket ban would be overbroad and undemocratic in its inclusion of members who are not guilty of any criminal activity and whose disassociation from political life would rest solely on the matter of their association. Such measures could include individuals such as the transitional prime minister, Essam Sharaf, who served in the Mubarak government and was a former member of the NDP’s policy secretariat, despite the absence or suggestion of any criminal or corrupt behavior on his part. This type of vetting raises the uncomfortable question of complicity, which is often diffuse in an authoritarian environment, but blanket bans on participation create a troubling precedent and erode the inculcation of democratic values. It is also disappointing, since the grounds for political exclusion of many politicians and supporters are obvious, whether on the basis of corruption, electoral fraud, or involvement in physical abuse.

Blanket bans would also prove ineffective in combatting entrenched political interests linked to power brokers. This key constituency within the constellation of NDP patronage networks is not dependent on individual personalities, and actual representation could be filled by any number of surrogates, whether relatives or business associates. While this should not forestall vetting efforts, certain longstanding concentrations of power will prove resilient to even the most draconian approaches.

A blanket ban on NDP participation would also be seriously underinclusive in light of the absence of NDP participation in the security sector. As opposed to the former Baath party in Iraq and the Baath party in Syria, the NDP was not a necessary prerequisite to career advancement within the bureaucracy and its membership did not extend to either the armed forces or the internal security forces. While a focus on NDP membership is understandable within the context of elections, vetting should be rooted in examination of past behavior and transgressions that go beyond mere party membership and focus on actual criminality, including electoral fraud and irregularities. In light of upcoming elections, however, vetting procedures would ideally be bifurcated so that judicial panels could certify the participation of individual candidates in the electoral process.

The second approach entails amendment of Qanun al-Ghadr, the moribund treason law established by the Free Officers in 1952. The original law served as a vehicle to purge political enemies and to entrench the power of the new regime. Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the law is its vagueness, since it lists political offenses as potential criminal acts. Without clear guidance rooted in the criminal code, this section of the law could prove malleable and might encourage overbroad application or wholesale purges. Introduction of the law would be poison within the body politic and encourage reckless accusations and the politics of character assassination. It is also unclear what gaps are filled by application of the law as opposed to reliance on the existing criminal code.

Creating a New Arab Order

As with Egypt’s outsized influence on the trajectory of political change in the region, the Egyptian experience with transitional justice will also shape regional understandings of the issue. Success or failure will either encourage or hinder similar efforts elsewhere.

What has emerged on a popular level across the Arab world is the erosion of an Arab order that prioritized the Palestinian cause and resistance to Israel and the West, to the detriment or exclusion of solidarity with the plight of other Arabs living under repressive rule. The emerging regional dynamic eschews this false dichotomy; it has continued to support the cause of Palestine while demanding that the social compact between ruler and ruled be refashioned in a way that affords citizens dignity and respect. Championing Arab causes and channeling hostility toward Israel and the West are no longer a sufficient buffer to domestic scrutiny and opposition, and a revitalized transnational solidarity has meant that repression is no longer ignored or an issue of secondary importance. The sustainability of these nascent shifts and the establishment of regional norms will depend on the broader success of the political and economic transitions now underway in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. How Egypt and other societies account for their often painful pasts will be an important measure of success, or failure.

Bibliography

Juan E. Mendez, In Defense of Transitional Justice, in TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND THE RULE OF LAW IN NEW DEMOCRACIES 1, 6 (A. James McAdams ed., 1997)

Jorge Correa Sutil, “No Victorious Army Has Ever Been Prosecuted . . .”: The Unsettled Story of Transitional Justice in Chile, in TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND THE RULE OF LAW IN NEW DEMOCRACIES, 123.

Tina Rosenberg, The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism, (New York: Random House, 1995).

George P. Fletcher & Jens David Ohlin, The ICC-Two Courts in One?, 4 J. INT’L CRIM. JUST. 428 (2006).

Ruti G. Teitel, TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE 39 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Monika Nalepa, Lustration, in THE PURSUIT OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL

JUSTICE: A WORLD STUDY ON CONFLICTS, VICTIMIZATION, AND POST-CONFLICT JUSTICE, Vol. I, 735 (M. Cherif Bassiouni, 2010) .

Priscilla B. Hayner, Fifteen Truth Commissions – 1974 to 1994: A Comparative Study, 16 HUM. RTS. Q. 558 (1994).

Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm, Truth Commissions and Other Investigative Bodies, in THE PURSUIT OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE: A WORLD STUDY ON CONFLICTS, VICTIMIZATION, AND POST-CONFLICT JUSTICE, Vol. I, 477 (M. Cherif Bassiouni, 2010).

Naomi Roht-Arriaza, Reparations in the Aftermath of Repression and Mass Violence, in My Neighbor, My Enemy: Justice and Community in the Aftermath of Mass Atrocity 121 (Eric Stover & Harvey M. Weinstein eds., Cambridge University Press 2004).

SCAF Communiqué No. 52, May 16, 2011, available at http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=215963445090579&set=a.191412130879044.43504.191115070908750&type=1&theater.

Kristen Chick, “Egyptian Report Details Brutality Against Protesters Before

Mubarak’s Fall,” Christian Science Monitor, April 20, 2011.

Anouar Abdel-Malek, Egypt: Military Society: The Army Regime, the Left, and Social Change under Nasser, translated by Charles Lam Markmann (New York, Random House, 1968) (first American edition)

John Waterbury, The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat:The Political Economy of Two Regimes (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1983)

Michael Wahid Hanna is a fellow and program officer at the Century Foundation. He is a regular contributor to the Atlantic and Foreign Policy’s Middle East Channel. He has been a senior fellow at the International Human Rights Law Institute, where he conducted research on post-conflict justice, victims’ rights under international law, and the Iraqi High Criminal Court. He is a term-member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter