Russia, Ukraine, and U.S. Policy in the Middle East

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has influenced U.S. policy in the Middle East, the future of which depends on the outcome of the war, as well as Washington’s commitment to the region

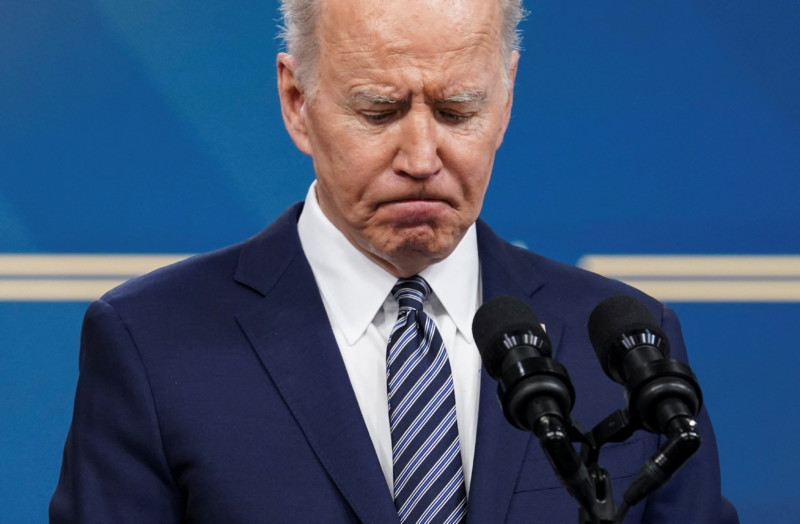

U.S. President Joe Biden during remarks in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building at the White House in Washington, March 31, 2022. Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

Three big power wars have come to define international relations in the first two decades of the 21st century—the United States’s misadventures in Afghanistan and Iraq, and currently the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Each in its own way has exemplified the African proverb: “When elephants fight, the grass suffers.”

These three wars, each fought for a different reason, share at least one thing in common: They negatively impact the confidence that allies have in their bilateral relations with great powers. The United States has experienced almost two decades of declining support from its friends in the Middle East, fueled by the U.S. military misadventures, the perception of diminishing U.S. interest in the Middle East, and by doubts about U.S. commitments to its traditional allies. American policymakers have sought to dispel doubts about American constancy and commitment, but the fact is that domestic priorities and shifting global trends toward Asia have reduced the capacity and willingness of the United States to do all that it used to in the Middle East, most significantly, taking the lead in advancing the prospect of Israeli–Palestinian peace.

As U.S. influence continued to decline over the past two decades, Russia for a while appeared to be gaining support and allies even among some traditional U.S. friends. Russian arms sales increased, especially after its military intervention in Syria in 2015. It appeared then that the Russians were the rising outside power.

However, Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine raised doubts among some in the region, and more recently, its military weaknesses and setbacks have cemented those doubts. Russia clearly is not a first-rate military power, and it does not have first-class leadership, either in its military or within its political elite. Middle East states are coming to understand that Russia does not represent a trusted alternative to the United States as an extra-regional power.

Unbalanced Narratives

There are at least eight important takeaways from Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine that impact the Middle East generally, and the United States specifically.

First, Western nations pay far greater attention to crises and challenges in the West than they do to problems in other areas. The situation in Ukraine has monopolized the attention of Western policymakers, focused on arming Ukraine, while dealing with refugees and displaced persons within the country. The direct impact of Russian aggression on European energy supplies and the threats by Russia’s leader of the possible use of nuclear weapons have dominated the policy planning of European governments and the United States. The decision by Sweden and Finland to join NATO, after years of choosing to remain outside the alliance, is a direct result of Russia’s aggression.

A second takeaway from the situation in Ukraine is the precarious nature of food security in the Middle East and elsewhere. With uncertain schedules and quantities of grain exports from Ukraine and Russia, many Middle East states are scrambling to meet the minimum food requirements of their people. Egypt, for example, is significantly reliant on grain imports from Ukraine and Russia, both for food and as “virtual water,”—the water it takes to grow the crops that Egypt imports as food.

A third related issue is global inflation and the impact of supply chain issues that started during COVID but have been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. The challenge of food security has worsened because of rising prices and uncertain supply. For some countries, the availability of food staples at inexpensive, often subsidized prices has always been an internal security problem, not just a health issue.

Fourth, Russia’s military setbacks and its pronounced military weaknesses have given pause to regional states that had hoped for Russian military support. More so, the fact that Russia is using Iranian “kamikaze drones” to terrorize the Ukrainian population sends a shiver through the halls of power in the Middle East. Gulf states and Israel were already seriously concerned about Iranian power projection in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen; this enhanced relationship with an aggressive Russia will deepen those concerns.

Fifth, the West’s reactions to Russia’s actions highlight what it is ignoring in the Middle East, such as ongoing state-directed terrorism in Syria, instability in Libya, the 55-year Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories, and unresolved disputes related to the Western Sahara and the GERD dam in Ethiopia. The Western bandwidth for active conflict mediation has narrowed considerably because of its diverted attention to Ukraine. The resources available to help vulnerable populations in the Middle East are shrinking and the patience for dealing with intractable conflicts and stubborn leaders is running out. Fatigue over conflict in the Middle East has given way to active engagement in the conflict in Ukraine.

Sixth, the breakdown in dialogue between the West and Russia has dimmed even further the prospect of a renewed agreement relating to the Iranian nuclear program. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), agreed in 2015, resulted from unprecedented cooperation among the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, both in the negotiations themselves and in the multilateral sanctions imposed on Iran after 2010. Without coordination today, the JCPOA negotiations are likely to go nowhere. The failure to reach agreement on reviving the JCPOA will create a significant threat of escalation in the region. Israel will ramp up its overt and covert military operations designed to disrupt the Iranian nuclear program. Military escalation risks engaging extra-regional players in a widening conflict.

Seventh, Russia’s aggression has placed Israel in a particularly awkward position, as it grapples with challenging contradictions among its interests. Israeli hesitation to condemn Russia has annoyed the United States and European countries. While Israel has provided humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, it has not responded to repeated requests from Kiev for anti-missile defensive systems, such as the Iron Dome. Israel does not want to alienate Russia, given the close ties between the Russian Jewish émigré community in Israel and their families still in Russia, as well as substantial trade ties between the two countries. However, Israel’s diplomatic tightrope walk appears to satisfy none of the major powers.

Finally, U.S. opposition to the Russian invasion has provided Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas an opportunity to blast American policy as hypocritical and unfairly biased toward Israel. His criticism reflects his disappointment over the Biden administration’s hesitation to reverse some of the damage done by the Trump administration, for example, the shuttering of the American Consulate in Jerusalem and the closing of the PLO office in Washington. Abbas was disappointed after meeting Biden and appeared to jump at the chance to embrace Putin and criticize the United States when he met the Russian president on the sidelines of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), in Astana, Kazakhstan, in mid-October.

Assessing U.S. Policies

Several of these factors—food insecurity and the perception of alliance unreliability—are tied directly to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, some of what we are witnessing now is old news, exacerbated by Ukraine, but in evidence well before the Russian invasion.

For example, many in the region believed the United States had started to pivot away from the Middle East toward Asia as long ago as the Obama administration. Never mind that the reality was far more nuanced; Obama invested significant time and resources in the region, including on the Israeli–Palestine conflict with John Kerry as Secretary of State. He also sought to reorient American policy in the Gulf, so as to create something of a balance of power between Saudi Arabia/ Gulf states and Iran, but that never meant abandoning America’s Arab allies or diminishing support for them in favor of Iran.

The Trump administration—for all the damage it did to U.S. interests in the region—also focused a great deal of attention on the region. This led to a strengthening of U.S. relations with Saudi Arabia which culminated in the Abraham Accords. Trump had no strategy for the region and allowed ideologically driven advisers to guide U.S. policy. But this led to an intensification of U.S. engagement with the region, not a diminution of interest.

President Biden, who entered office intent on domestic transformation, has pursued a relatively active policy in the Middle East, both prior to and since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, however poorly executed, extracted America from what seemed like a never-ending war, thus removing a significant irritant in Arab public opinion. Active U.S. diplomacy in Yemen, bolstered by Biden’s appointment of a talented special envoy with significant regional experience, Ambassador Tim Lenderking, has contributed to the ceasefire there. The administration has also taken steps to reverse some of the most malign aspects of Trump’s policies toward the Palestinians by restoring assistance, resuming aid to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), and establishing an independent diplomatic reporting channel from the Palestinians to Washington.

With regards to the U.S embassy, the administration cannot move the embassy back to Tel Aviv for at least two reasons: There is a law on the books requiring the embassy to be in Jerusalem; and there is no political support among Democrats or Republicans to move it. That said, President Biden can still find a way to put Jerusalem back on the negotiating table—after Trump said that he had removed the issue from the table—and to address Palestinian requirements of having their capital, and the U.S. embassy, in Jerusalem when a Palestinian state is established.

The real test of how the Russian invasion of Ukraine will impact U.S. policy in the Middle East is yet to come. One indicator will be the degree of American constancy, that is, whether the United States can continue to pour billions of dollars of military equipment into Ukraine, or whether domestic politics will force a change in policy. A second factor will be the unity of the anti-Russian alliance, as winter impacts Europe with diminished and more expensive energy supplies.

For the time being, the United States has proven capable of “walking and chewing gum,” that is, the U.S. administration continues to put pressure on Russia by supporting Ukraine, and it continues to engage on a number of Middle East issues. One example: the successful maritime agreement between Lebanon and Israel, mediated over several years by the United States. Absent a significant reversal of Ukrainian fortunes, these two pillars of American policy are likely to remain unchanged.

Daniel C. Kurtzer is S. Daniel Abraham Professor in Middle Eastern Policy Studies at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs. He served as the American ambassador to Israel (2001−2005) and to Egypt (1997−2001). Instrumental in formulating and executing U.S. policy toward the Middle East peace process, he participated in the team that convened the Madrid Peace Conference in 1991. He is the co-author of The Peace Puzzle: America’s Quest for Arab-Israeli Peace, 1989-2011.

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter