Anatomy of a Revolution

The fight against racialized violence in the U.S. prison and policing system has characterized the last fifty years of the struggle for racial justice. In 2020, new momentum marks a historic moment.

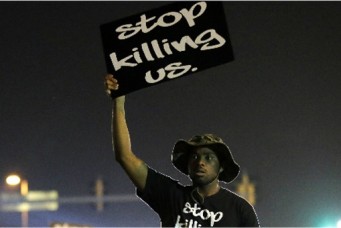

A demonstrator stands in front of New York Police Department (NYPD) officers inside of an area being called the “City Hall Autonomous Zone” in New York City, July 1, 2020. Andrew Kelly/Reuters

From May to August 2020, protests calling for justice for black people in the United States were held from Minneapolis to Portland; New York City to its surrounding suburbs; London to South Africa; and Iraq to Palestine. These are not new, they are the latest step in a racial justice movement that has been in effect for more than a century. However, today’s movement is unprecedented in scope; this time, anger has found a new outlet in social media, demands have taken a fiscal orientation, and, as a result, protests have reverberated far wider than they had before.

After Michael Brown was killed in 2014, the largest racial justice demonstrations seen since the 1960s erupted in the city of Ferguson, Missouri. In 2020, the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, among many others, incited protests that dwarfed Ferguson, both throughout the United States and abroad.

If today’s moment is to be analyzed, the victims that inspired it deserve to have their stories told. Forty-six-year-old George Floyd was killed on May 25 when Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds, despite the illegality of the restraint and Floyd’s pleas of “I can’t breathe.” On May 29, Chauvin was arrested and charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter; on June 3, those charges were upgraded to include second-degree murder, and three other officers who were involved—Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng, and Tou Thao—were also charged.

Protests began in Minneapolis after a cell phone video showing Floyd’s death was circulated online, and the demonstrations quickly reverberated through surrounding states. At that point, the story of Breonna Taylor, a twenty-six-year-old medical worker from Louisville, Kentucky, also gained traction. Taylor was shot dead in her bed on the night of March 13. Police officers had entered her home under the authority of a no-knock warrant in connection to a drug case, and later realized that they had entered the wrong house. The officers’ names are Brett Hankinson, Jonathan Mattingly, and Myles Cosgrove. Though none have been charged for Breonna’s death, her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, was charged with assault and attempted murder for firing his gun in defense, unaware of who was barging into the home. The charges against Walker have been dropped, but there has been no accountability for the killing. Of the three officers, only Hankinson has been fired from the police force.

Although Black Americans make up 13 percent of the U.S. population as of 2019, they comprise 23 percent of the victims of police brutality; 1,098 Americans were shot and killed by police in 2019, 249 of which were Black. Each year, a few stories make national news; consider Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile, Stephon Clark, and Sandra Bland. However, the vast majority of the stories of the black victims of American policing remain untold. Social media is making some progress in putting names to this statistic. However, drawing attention to the scope of the policing problem is just one tenet of the movement’s objective. To prevent further deaths, the movement seeks to dramatically alter the ways that communities solve problems.

“What Do We Want?” “Justice!”

The objectives of the 2020 movement can be boiled down to one core demand: “Quite simply, it is to keep from dying,” Stefan Bradley, professor of African–American studies at Loyola Marymount University and author of Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power and the Ivy League, told the Cairo Review. Hence the movement’s rallying cry: “Black Lives Matter” (BLM).

As a result, the phrase “defund the police” has become part of the movement’s lexicon. The language reflects the idea that taxpayers deserve resources that work for them; thus, the movement to defund looks to lower police budgets and reallocate their funds toward underfunded preventative crime measures such as social work, education, and mental health resources. On June 8, Congressional Democrats introduced the Justice in Policing Act of 2020, which includes a bundle of reforms, requiring the use of body cameras, banning chokeholds, ending no-knock warrants in drug cases, and making lynching a federal hate crime. But, there was no mention of ending federal funding for local police, which reached over $1 billion in fiscal year 2020 through various initiatives.

In addition, many are arguing that reforms just do not work. In an op-ed for the New York Times, anti-criminalization organizer Mariame Kaba pointed out that reforms rely on the assumption that rules will be followed; although Minneapolis had passed a “duty to intervene” policy in 2016 in an attempt to force officers to hold each other accountable for inappropriate use of force, Keung, Lane, and Lao stood by as Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd. “What we’ve got to get to is the culture of policing at this point,” said Bradley, noting that it was the culture of policing that caused the other three officers to value Chauvin’s seniority over Floyd’s life.

Some activists take the call to defund a step further; for them, it demands the complete abolition of police forces. “We can build other ways of responding to harms in our society,” Kaba wrote. She suggested that “trained ‘community care workers’ could do mental health checks if someone needs help. Towns could use restorative-justice models instead of throwing people in prison.” Such models include holding offenders accountable by rehabilitating their relationship with victims and their families rather than isolating them in the criminal justice system.

The abolition argument asserts that reform is impossible in a system with inherent malintent. Federally-funded, official “police departments” began to spring up in the North in the nineteenth century, but during the post-Civil War Reconstruction of the late 1800s in the southern United States, “many local sheriffs functioned in a way analogous to the earlier slave patrols, enforcing segregation and the disenfranchisement of freed slaves,” writes Olivia B. Waxman for Time. Those slave patrols were fully sanctioned in any state where slavery was legal, and had the authority to enter lodgings, quell uprisings, inflict punishment, and return slaves who had run away from their plantations.

African slavery was fully institutionalized when the first trading ship from Angola arrived in Jamestown as early as 1619. All this is to demonstrate that the United States benefited from African subordination before it even became a state that could sanction it on its own; racial violence toward Black people is in the country’s DNA, and it created a hierarchy that was grandfathered into the creation of “American” institutions.

Though “slavery,” in the strictest sense of the word, was ended by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, this is a half-blind interpretation of history. Historically, every structure of racial oppression in the United States has been abolished simply to be rebranded; slavery warped into sharecropping agreements, which warped into Jim Crow segregation, which warped into a system of mass incarceration and violent policing that disproportionately affects Black people. As such, the fight for racial justice has evolved in turn. Abolitionists became the civil rights leaders of the 1960s, the Black Panther Party and the followers of Martin Luther King, Jr., who became the people on the streets today.

The Social Media Vector

Social media was integral in the formation and organization of the 2020 protests, and further distinguishes the 2020 movement from past phases of the racial justice struggle. “Anyone who has one of these,” said Diana Carlin, Professor Emerita of Communication at St. Louis University, holding up her phone, “is a journalist and can tell a story.”

The American public was brought face-to-face with police brutality when a video of Floyd’s death captured by seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier went viral. As individuals took their phones to protests, they shed light on brutal tactics used by police to repress the demonstrations, which just further galvanized support for the cause. T. Greg Doucette, a Virginia-based attorney, is just one example of the rise in citizen journalism. His “Police Brutality Mega-Thread” on Twitter documented over 850 instances of excessive force against protestors from May to July 31, 2020.

Doucette documented a host of the tactics utilized by police, including the use of rubber bullets and tear gas. As of June 18, the New York Times had documented the use of tear gas in one hundred U.S. cities, despite the substance’s illegality in warfare under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). USA Today reported on June 22 that at least seven people had lost eyes after being shot with rubber bullets, which are sometimes used even despite bans within local departments. Law enforcement justify their use of force under the pretext of quelling looting, rioting, and other violence aimed at officers. However, although acts of violence have been committed by some protesters, over 93 percent of protests have been peaceful, and the level of violence committed by law enforcement has exceeded what is necessary.

At the end of July, the city of Portland emerged as the epicenter of violence. The beginning of August marked over sixty consecutive nights of protest in the city. Like its counterparts in other U.S. cities, Portland’s demonstrations were mostly peaceful; however, after a federal courthouse was vandalized and fire was set to the Portland Police Association, federal agents entered the city under the authority of an executive order issued on June 26 to protect monuments and statues. These federal officers began seizing protesters from the street, transporting them in unmarked vans, and detaining them without cause. Though the federal agents vacated the city in the beginning of August, they left behind a legacy of state-sanctioned brutality. Physicians for Human Rights concluded that the response by federal agents that it documented in Portland was “disproportionate, excessive, and indiscriminate, and deployed in ways that caused severe injury to innocent civilians, including medics”. President Trump dismissed reports about these abuses as “fake news”.

Lastly, journalists in the United States have themselves been targeted by police. The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker documented over six hundred press freedom violations in the country from May 26 to August 6. In its own analysis on press freedom violations with Bellingcat, The Guardian wrote: “Reporters in Minneapolis, Louisville, or the dozens of other places that witnessed protests and riots in the days after the alleged murder of George Floyd were not killed or prosecuted, as they increasingly are elsewhere in the world. But they were blinded, beaten, maced, and arrested by police in numbers never before documented in the U.S.” Moreover, The Guardian notes that, in seven out of ten instances, journalists attacked by police forces were visibly displaying press credentials. Take, for example, CNN reporter Omar Jiminez, who was arrested along with his production team while broadcasting on-air. It is worth noting that Jiminez is Black and Latino, and that white CNN reporter Josh Campbell was allowed to remain in the area.

Partners in Solidarity

“We always said Ferguson was everywhere, but I don’t know if we ever imagined this kind of reaction throughout the world,” Bradley said, remarking that it would have been unfathomable in 2015 to imagine solidarity protests in over forty countries like those that have been held since May. This global spread is also unique to the 2020 phase of the racial justice movement, and owes at least part of its breadth to the role of social media.

The countries standing in solidarity with the United States are diverse; protests have been held on every continent besides Antarctica. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization and former British Commonwealth countries led the solidarity protests, with demonstrations in twenty-four cities in the United Kingdom; thirteen in Australia; six in Germany and France each; and four in Canada. Activists in Middle Eastern countries have also responded, including in Israel, Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq, and Palestine. In Bethlehem, Palestinian artist Taqi Spateen painted a mural of George Floyd on the barrier wall separating Israel from the West Bank. “I want the people in America who see this mural to know that we in Palestine are standing with them, because we know what it’s like to be strangled every day,” Spateen said in an interview with Mondoweiss. “I want justice, not O2,” the mural proclaims in English.

As seen in the Palestinian case, the global protests often refract the message of BLM to their own governments. In Australia, for instance, protests are in solidarity with the country’s Aboriginal population as much as they are for George Floyd. Since 1991, over four hundred Aboriginal people have died in police custody, and Aboriginal adults are fifteen times more likely than their non-Aboriginal counterparts to enter the prison system. “Australia is not innocent,” the country’s protesters shouted.

Bradley spoke to the effect that watching global protests for Black justice has had on him, having grown up being taught that America was supposed to fight for freedom for others. “I never thought I’d get to the point where there are people in other nations lobbying for justice for American citizens in such a loud and resonant way,” Bradley told the Cairo Review “I feel comforted that the world recognized us, but I also feel embarrassed that that had to happen.”

What Now?

It has been proven that protests can force change. George Floyd’s killers are being prosecuted, and twelve cities have heeded the call to cut police budgets. However, most budget cuts remain incremental. New York City cut funding to the New York Police Department by the largest dollar amount—$1 billion from roughly $5.6 billion in FY20—but it had the largest budget in the country to begin with, and about half of that “reduction” is accounted for by shifting personnel and departments to other agencies, writes Steve Malanga for the Manhattan Institute.

Some officials have voiced support for radical change—a veto-proof majority of the Minneapolis City Council voted to disband their police department, and the same quorum of the Seattle City Council voted to slash the police budget by 50 percent—but their promises have been blocked by bureaucracy and are yet to be realized on the ground. Though “Breonna’s Law,” which bans no-knock warrants, was passed in Louisville, her killers walk (and work) freely.

In these cases, officials make clear that they view placation, or acts that appease the public but are not serious steps toward reform, as an adequate substitute for justice. Take, for instance, the assortment of murals proclaiming “Black Lives Matter” that have appeared across the country. BLM murals have been publicly funded in over thirty states; however, those same states refuse to make tangible changes to their budgets (i.e. New York). Art is powerful, but the people know when it’s being used as an opiate.

However, at least the movement has thrust such conversations into the spotlight, Bradley and Carlin agreed. With the movement plastered across social media, it is difficult for politicians to skirt the subject. Bradley acknowledged that structural change will be more difficult at the federal level, which is distanced from local police units. However, there is a common desire among protesters for a change in the administration come November. “I think for a lot of young people—particularly those who are coming of age, turning 18 years old, voting in their first election—this is going to be a changing of the guard in a lot of ways,” he said. “But, I’m also skeptical of the contingent of people that says ‘If you vote, all this will go away’. That’s not how American history works,” he warned. It is not enough just to create laws; they need to be enforced as well. At the end of the day, there’s a culture constituted by community–police relations that needs to be drastically changed.

Instead, in Ferguson, some of the activists become candidates for political roles, Bradley continued. This is already happening via state primaries. In August, Cori Bush, who was a lead organizer of the Ferguson movement, ousted twenty-year incumbent William Lacy Clay in the Missouri Democratic Primary. This new wave of leaders is already being bred. In the United States, 90 percent of adult social media users are between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine, many of whom took to and used Instagram, their third-most favored platform, as a depository for activism and justice. After George Floyd’s death, users began to share petitions, links to organizations seeking donations, photos of protests, antiracist readings, and other informational plaques on their Stories with unprecedented frequency.

The watershed moment that racial justice organization is at in 2020 is not the movement’s first, nor will it be the last. But, to make progress, the country needs to understand just how deep the issue cuts; to think that racism is relegated to the past or that racial justice organization is uniquely modern is yet another symptom of white supremacy. Without first extinguishing this core fallacy, any change will fail to assess the entirety of the problem. What’s different about today’s moment is that, with the world completely connected online, it is significantly more difficult to turn a blind eye to the history of your country. And, with the world at a unique pause, the manpower dedicated to sharing information has significantly increased. Hence, the creation of new ideas, like defunding the police. What is yet to be seen is if the momentum can make its way to the polls—not only on November 3, but at the local level—and whether sitting politicians will have the courage to respond to their constituents’ demands.

Sydney Wise is contributing editor at the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. Her past work has been published at the Boston Consortium for Arab Region Studies. On Twitter: @sydneyywisee

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter