How to Deal with COVID-19 in Africa

Strengthening the capacity, the data networks, and the community response to win against COVID-19.

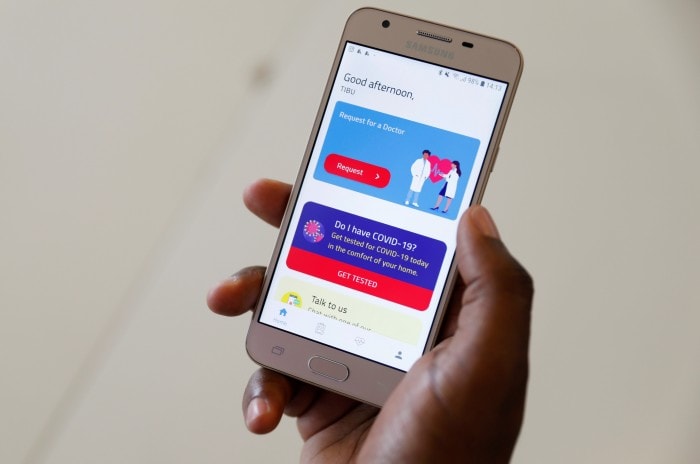

A man displays the TIBU Health app of the Nairobi-based startup on his phone in Nairobi, Kenya May 22, 2020. Picture taken May 22, 2020. Baz Ratner/Reuters.

Health is a catalyst for socioeconomic transformation. In the Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19 (PERC)’s May 7 report titled Responding to COVID-19 in Africa: Using Data to Find a Balance, three recommendations were put forward. They are not new in the context of what Africa has been doing to keep its citizens safe from most common illnesses such as malaria, Neglected Tropical Diseases, Lassa Fever, diarrhea and other diseases that have shaped the relationship between citizens and their environment. As such, building public health capacity, monitoring data, and engaging communities are central, not only in responding to COVID-19, but in confronting issues such as jobs, agriculture, and other challenges. We must confront all of these points as we work to transform our economies.

The Dual Target: Good Public Health and a Good Economy

Having a goal to strengthen public health capacity is not a new narrative. COVID-19, however, has wrought a massive health and economic disruption. The economic disruption affects the most vulnerable, as the lack of physical proximity destroys their businesses in the informal economy. Thus, the vital injection of resources to support their daily lives disappears and the measures required to ensure that individuals do not contract the virus contradict the economic system that keeps some of us fed and provides for their livelihoods.

Building capacity is a two way street where the benefits of adhering to public health measures do not limit short, medium, and long term economic benefits. The PERC report indicates that about one-third of respondents, in all African regions, expressed opposition toward measures related to workplace and market closures. Public health and economics are generally uneasy partners until the lack of effective health and social measures threaten lives in a pandemic. Many respondents stated that they defied the COVID-19 protective measures put in place by states across the continent with 83 percent of respondents in Western Africa, stating there were unable to stay-at-home as food and water are often not accessible at their homes. In Central Africa for example, 61 percent of respondents believed that running out of money is a reasonable reason why not to respect confinement orders. Yet, in Northern Africa only 19 percent of respondents in the PERC report cited losing a job as their main motive for breaking anti-COVID-19 procedures.

People do not need medical attention at scale, they need access to decent jobs and preventive measures. While the African continent has been good at taming viruses and disrupting transmission chains, we have had poorer success at creating decent jobs. As such, prevention needs to be the key enabler of strengthening public health capacity for a person’s journey through the system. We must no longer have a system based on vertical diseases funding. We know today that COVID-19 is, potentially, reversing twenty years of progress in malaria. The era of single disease funding has got to come to an end.

Monitoring data never used to be that important. That a virus has put a spotlight on the lack of reliable data on the continent is a good opportunity for Africans to use the tools at hand to share data with health authorities. A cellphone with existing technologies can ensure that those with symptoms can inform, at distance, health authorities. One can imagine how the spread of Ebola—a much more virulent virus—could have been limited if we had been able to use the existing infrastructure to share data and monitor the situation in the regional community.

The COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed the innovative spirit of many African entrepreneurs. In Burkina-Faso, for example, the application “DiagnoseMe” is a success story. It allows individuals to check their exposure to COVID-19 by simply filling out a form. If infected, the application connects them to the relevant social and medical services. As far as states are concerned, many are focused on tracing and tracking technology which make it easy to locate potentially infected persons, and limit the movement of those already infected.

These methods are in the implementation phase in South Africa, where through a partnership with local mobile operator Telkom, tracing and tracking services are rendered possible. In Morocco, the Minister of Interior unveiled the application “Wiqaytna” (Arabic for “safety”)—recently approved by the data protection and privacy watchdog—allowing individuals downloading this application to be notified every times they are close to person tested positive for COVID-19 in the last twenty-one days. Technology as a public good, however, has limitations when it comes to confidentiality and data privacy. To date, five out fifty-five African Union Member States have adopted, since 2014, the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Data Protection. Yet, basic human rights are challenged by domestic legal vacuums in terms of legislation governing how data is collected, and legal avenues for citizens to seek redress in case of violation.

It is important to acknowledge, as stated in the PERC report, that Africa’s COVID-19 response demonstrated coordination in the early phase of the pandemic which was critical in reducing the spread. As our governments’ separate responses have evolved, we are now able to take into account our specificities. Clearly, the one-size-fits-all approach in dealing with COVID-19 has not been applicable to a continent as vast as Africa.

Engaging Communities

Community engagement in response to the COVID-19 pandemic leads policymakers to think of demography first. With better data now available from other parts of the world, we see that the health impact of the virus on senior citizens has been devastating. Meanwhile, economically, the real challenge might be now on Africa’s relatively young population—45 percent of the continent’s population is less than fifteen years old. Over the past few months, young people have had to contend with preventive measures against COVID-19 all the while trying to find decent employment.

Our hope is that, as things improve in our response to the pandemic, there will be no better health response than the ability to spur the economy toward full employment of its resources. A new job opens opportunities for individuals and their community to prevent themselves from diseases and increase their community’s wealth. A key pillar in this approach should emphasize as well the importance of a sensitization campaign toward communities being served.

Recently, news in and out Africa is saturated with COVID-19-related information. But is the right information known? Is the African layman or woman familiar with the methods of transmission of the pandemic? Those are the questions the PERC report tried to pinpoint.

Only 13 percent of the surveyed population knew that an infected person may not show up any symptoms for five to fourteen days. When respondents do know about the pandemic, there is a need to fine-tune their knowledge, as 32 percent expressed a desire to learn more about the pandemic. This is an encouraging finding, as accurate information is a catalyst for prevention against COVID-19 and other diseases. Thus, factual communication is the responsibility of citizens and their governments. Misinformation, however, is an opposing force that leaders must combat with the same vigor as the virus. Viral misinformation may claim lives and breed parallel theories of change around the world.

One of these issues is related to clinical trials for vaccines. While we are in the early stages, communication about protocols and mechanisms are extremely important, even if some regional African countries do not participate in the clinical trials. While waiting for vaccines, people’s imaginations and beliefs often seek a common understanding of what could boost their immune system.

Ultimately, effective communication passed on from generation to generation is helpful when accurate. The same should apply to engagements with local leaders. Providing these leaders with accurate information on the coronavirus ultimately will help these leaders in guiding their communities’ multimedia consumption. And, we know that the key to fighting COVID-19 and other diseases in Africa lies with government and health officials having the ability to consult, listen and help local leaders tailor the message with accurate and relevant information for their communities.

Not a Passing Storm

COVID-19 puts a finger on the pulse of vulnerable communities. As policymakers, we cannot just check and leave. There is a great risk related to employment conditions, further challenged by prevention measures. As an African society, we know that this pandemic is the turning point in how we deal with access to health for the most vulnerable.

This crisis is not a storm that will pass. It will stay with us, and mopping up will not be enough. Restricting physical proximity has undoubtedly an economic cost. An exit strategy recognizes that the virus is with us to stay in different waves. Thus, public health capacity, data, and community participation are the holy alliance in making citizens adhere to measures that will fire the economic engine while maintaining the progress made in putting health at the center of the economic response.

Arnaud OULEPO is a Research Associate at the Centre of Research for International Cooperation and Development at University Cadi Ayyad. Former intern at a World Bank Group Institution, he regularly comments on African politics, economics and development issues.

Read MoreCarl Manlan works at the intersection of public, private, and civil society sectors at Ecobank Foundation in Lomé, Togo. He is a graduate of Harvard Kennedy School and the author of numerous articles on African economic transformation. On Twitter: @CarlManlan.

Read MoreSubscribe to Our Newsletter