Saudi Arabia Is Not “Sunni Central”

Unlike what many Western pundits think, Saudi Arabia does not represent the “true” Sunni Islam. Even within the country, there are older traditions of Islam that are far more open and tolerant than the Kingdom’s official Wahhabist sect.

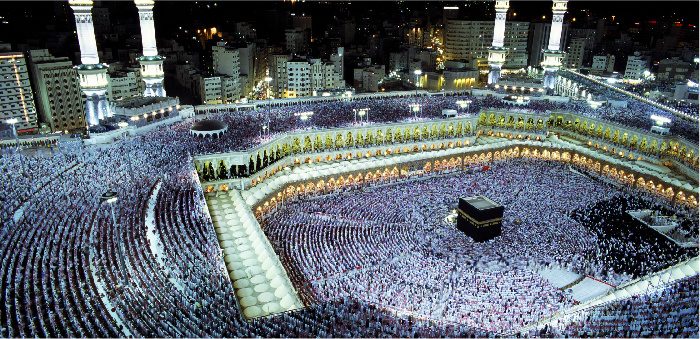

Pilgrims at the Grand Mosque, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Kazuyoshi Nomachi/Corbis

In his column in the New York Times on November 27, Roger Cohen described Saudi Arabia as “Sunni Central.” It is not, was never so, and will never be.

“Sunni Central” means, or implies, being the heartland, or embodiment, or representation of Sunni Islam. Islam was born in the region Al-Hijaz, which since the second decade of the twentieth century after a succession of military battles led by Abdulaziz Al-Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia, has become the western province of the kingdom bearing the family’s name. But whereas the traditionally austere culture of Najd (the central part of Arabia dominated by Bedouin and tribal heritage) shaped the kingdom’s culture, Al-Hijaz has always been a trading hub, a place where Yemeni, Levantine, Egyptian, and local cultures interacted. And so, despite the nine-decades long political link between Al-Hijaz and the rest of present-day Saudi Arabia, Al-Hijaz has retained its distinct cultural and social milieu, which is vastly different from those of the kingdom’s other regions. Invoking any historical or cultural link between Al-Hijaz, the birthplace of Islam, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, confuses traditions and heritages.

Embodiment entails being, in the perception of at least a majority, a prime example of the values associated with, or indeed a clear expression, of Sunni Islam. The history of Sunni Islam does not lend any of that to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The political, social, and to some extent theological expressions of Sunni Islam evolved during the times of the Umayyad, Abbasid, Mameluk, and Ottoman dynasties, from the eight to the eighteenth centuries. These took shape in the, at the time, culturally diverse, and to a large extent cosmopolitan and socially tolerant (many in Saudi Arabia would say decadent) Levant, Iraq, Egypt, and Ottoman heartlands in Asia Minor. These could not be more different in their social influences and theological understandings of Islam from Wahhabism, the highly strict, almost literalist discipline that the Al-Saud family allied itself with in the eighteenth century. This is one reason why Wahhabism remained almost totally confined to the Arabian peninsula up until the early 1970s, when millions of poor and lower middle class Arabs from the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa emigrated to the Gulf, and especially to Saudi Arabia in search for jobs after the exponential increase in oil prices in that decade.

All of this makes the notion of Saudi Arabia representing the “true” Sunni Islam highly fraught. It is important to note that despite being the richest Sunni-majority country in the world, the host of Al-Hajj (the annual Islamic pilgrimage that attracts millions of Muslims every year), and one of the very few Islamic countries in which a group of scholars (the Wahhabi establishment) have a highly influential role in key areas such as education, Saudi Arabia has never managed to establish a religious institution that commands global veneration in the Islamic world, such as that enjoyed by Egypt’s Al-Azhar or Tunisia’s Al-Zeituna.

What leads many observers—not only in the West—to confer on Saudi Arabia the positioning of “Sunni Central” is that, for half a century now, the country has been trying to export the Wahhabi understanding of Islam to the rest of the Sunni Islamic world. It has also been, by far, the biggest and most prominent financier of some Islamist groups, especially in the West. And in the hot-spots where Sunni Islamic forces were drawn into religious or sectarian tensions, for example in Lebanon since the late 1970s, and in Iraq since the mid-2000s, Saudi Arabia has indeed supported the leading forces of Sunni Islam, even if they had no connections at all to Wahhabism.

But that support was always selective. In the 1950s, Saudi Arabia forged a brief alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood, as the two saw in the secular Arab nationalist movement (and its towering representative, Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser) a common enemy. But, Saudi Arabia, whether its political or theological elite, quickly developed many apprehensions against the Brotherhood. More recently, in the last five years, Saudi Arabia emerged as an opponent of—and in some cases saw a strategic threat in—the Brotherhood, Turkey’s Islamist AKP party (which has ruled the country since 2002), and Tunisia’s Ennahda Movement (which arguably has developed one of the most sophisticated attempts by a political Islamist group to reconcile Islamism with secular modernity). And so, Saudi Arabia’s support of Sunni Muslim actors has always been subject to either the kingdom’s interests or its theological discipline, or both.

The notion of Saudi Arabia as “Sunni Central” creates many problems for Sunni Muslims, the world, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia itself. This notion dilutes the rich heritage of Sunni Islam into one of its severest and most rigid interpretations. Without intending it, this notion strengthens the ideologies that reject the Islamic world’s historical episodes of pluralism and openness to intellectual and cultural engagement with the world. It also subtly strengthens the ideologies that permit the usage of violence to spread its presence. It betrays the confusion of many in the West, including in supposedly well-informed circles, of the ideological and cultural struggles that lie behind many of the cold and hot wars that are currently raging across the Middle East.

This notion of being “Sunni Central” also presents Saudi Arabia with a colossal responsibility: of playing a leading role in finding a new way of reconciling secular modernity with Islam as a social frame of reference, identity, and a system of governance and legislation. Despite its wealth and the prestige conferred on the kingdom as the host of Islam’s holiest shrines, Saudi Arabia is unprepared to assume that responsibility. Because of its relatively young age and still limited political experience (the country of Saudi Arabia is less than a hundred years old), the economic and technological changes that are consistently bringing down oil prices and diminishing oil wealth (the fuel that has sustained the project of King Abdulaziz Al-Saud in the last seven decades), and the kingdom’s demographics (over two-thirds of its population under 30-years old, with one of the world’s highest rates of exposure to satellite and digital media), Saudi Arabia is compelled to undergo a transformation of its political and social system to absorb the ambitions—and frustrations—of the majority of its people. And this is happening at a time when the first generation that has ruled the country in the last seven decades (that of Abddulaziz’s sons) is handing over to the next generation of the grandsons, with all the tension and uncertainty that come with such transfer of power, especially in a highly closed structure. Saudi Arabia has its own colossal challenges to confront, to be able to assume any genuinely leading role in the Islamic world that is undergoing its own fraught transformation.

Understanding the diversity that has always characterized and shaped the Sunni Islamic world is key to isolating and diminishing the narrow minded and pugnacious ideologies that are the product of the most frustrating episodes of Islamic history, and which today plague Sunni Islam.

Tarek Osman is the author of Egypt on the Brink and the forthcoming Islamism: What It Means for the Middle East and the World from Yale University Press. He wrote and presented the BBC series “The Making of the Modern Arab World” (2013) and “Sands of Time – A History of Saudi Arabia” (2015). He is the political counselor for the Arab World at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter