North Africa’s New Directions

Unsteady leadership in the Maghreb could lead to new problems, both on a local and regional level.

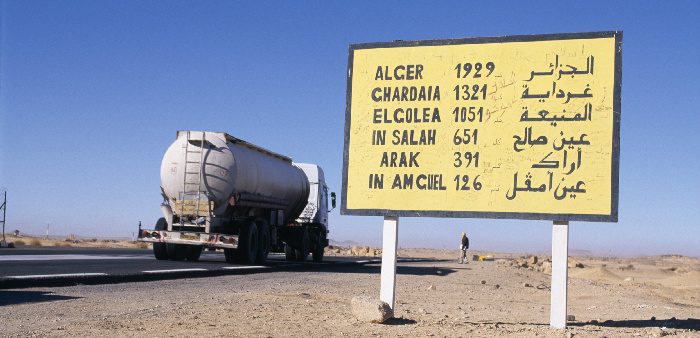

Truck passing road sign in Tamanrasset, Algeria. Frans Lemmens/Corbis

There is mounting speculation that the Western European countries with or without NATO are—yet again—thinking of intervening militarily in Libya. In this case the purpose of what is claimed would be a “limited” engagement would be to prevent the “Islamic State” (also known as ISIS) from consolidating its base on the Libyan coast in Sirte.

So many armed interventions in the broader Middle East and Central Asia since 2001 have come unstuck that a measure of skepticism is only to be expected. Others argue that Europe can hardly let an ISIS base consolidate just across the sea from southern Italy. They have a point: if successful, such an operation could help stabilize a region which is beset by many conflicts that play out both domestically and regionally and, beyond the immediate neighbors of Libya and the European Union, draw in actors from afar—the United States, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. It could however backfire spectacularly, as indeed it did in 2011-12 when the state of Mali came close to collapse thus prompting a French military intervention.

Were Libya to be stabilized—a huge “if”—Tunisia will head the list of beneficiaries. Libya has lost $68 billion in oil revenues since 2011. North Africa’s smallest country already hosts an estimated one million Libyan refugees and stands to gain from a more stable southeastern neighbor. This would help contain the growing free trade no-man’s land that Tunisia’s southern province Ben Gardane has become, a region through which any number of weapons, drugs, and Asian-made manufactured goods are smuggled into the country while avoiding any tax. Tunisia would be able to step up its security cooperation with Libya where many of the more than five thousand Tunisian jihadi fighters who have spread out beyond the borders of their homeland have been trained. A more stable Libya could return the country to the position held for centuries, that of being a close economic partner with Tunisia, to the mutual benefit of both. Were such an operation to fail, however, the blowback effect on Tunisia would be very destabilizing. A flat economy and many difficult social and economic problems are already taxing Tunisia’s young democracy to the limit—an even more chaotic Libya would only make matters worse.

Factors that attract outside interest include the control of oil and gas resources, social and economic rents, political posturing and security issues which have become ever more difficult to define as the lines between terrorism and smuggling become more blurred. Domestic factors, however, outweigh regional ones. Despite two free general elections and one free presidential one, the Tunisian government seems unwilling or incapable of launching a policy of bold economic reform, one which would share wealth with greater equity and, through a policy of rehabilitating the periphery, heal the growing economic and social chasm between the far more developed coastal areas and the poorer hinterland.

The attack against the presidential guard in Tunis last November allowed the president, Beji Caid Essebsi, to move back into senior posts at the interior ministry people who were disgraced after Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali’s fall. The new director general of security is none other than Abderrahmane Belhadj Ali, the head of the former dictator’s security guard. The ministry’s budget has increased by 7.6 percent in 2016 at a time of stringent economic austerity. The country’s economy is reeling from the collapse of two of its key export sectors, tourism and phosphates. The latter reflects the continuing and bitter labor conflict in the phosphates mines of Metlaoui, in the country’s poor southwestern region bordering Algeria. The revolt of the phosphate mines was repressed with great harshness by Ben Ali in 2008—it was in fact the forerunner of the revolt which unseated him in 2011.

The government led by Prime Minister Habib Essid lacks authority and dares not promote public investment, which is the only way the country’s economy could grow. His weakness in turn detracts private investors, Tunisian or foreign, from putting money into manufacturing and creating desperately needed jobs. The foreign debt is rising inexorably and a rescheduling next year can no longer be ruled out. As the economy sheds jobs and unemployment rises, younger Tunisians—who abstained massively in the last elections—have lost whatever hope they entertained five years ago of a better future.

Neighboring Algeria, meanwhile, is going through an interminable succession crisis. President Abdelaziz Bouteflika is essentially out of commission and this has allowed his brother, Saïd Bouteflika, to gain ever more influence. Some of Algeria’s war of independence heroes claim that a “soft coup” has taken place which will usher in a louche republican monarchy—a sobering thought in a country which was once a leader of Third Worldism and the keen supporter of the cause of the Palestine Liberation Organization and the African National Congress. The dismissal of the head of security who held his job for twenty-five years, General Toufik Mediene, and the public exchange of insults between the presidential clan and senior officers thtat followed is unprecedented in the history of modern Algeria. Never have senior officers been arrested, put on trial and condemned to prison sentences—infighting at the top can, if taken too far, spill over into the streets. There is plenty of inflammable material around.

This political uncertainty needs to be set against the backdrop of an economy that has been hit hard by the decline in the country’s foreign oil and gas income from $63 billion in 2013 to $33 billion last year—something that the rudderless government led by Abdelhamid Sellal has quite failed to anticipate. Projects are being cut right, left and center with no logic and without any warning to the regions, which suddenly see one of their pet investment projects airbrushed out of the budget. Price rises have so far met with a muted social response, but bearing in mind that direct and indirect subsidies accounted for a staggering 29 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2013, price rises in petrol, foodstuffs, and electricity are inevitable. Although the average income reached $5,000 in 2011, it is very unevenly distributed. Unemployment among young people meanwhile runs at an estimated 30 percent—the state offers few incentives to those who wish to train or set up their own business.

During the years of fat cows, Algeria witnessed huge expenditure on overpriced infrastructure. Now, corruption is worse than it ever has been and the economy has not diversified. Forty years ago, 30 percent of GDP was invested in the industrial sector, a figure which has fallen to 10 percent in the past decade. That is less than one third of many middle-ranking countries. This explains why Algerian diplomacy, despite the talent the ministry of foreign affairs can claim, boxes below its weight internationally. True Algeria plays an active role in regional diplomacy but that is nothing as to what it could do were its economy on a sounder footing and its future political course less uncertain.

The Algerian army is working hand in hand with its Tunisian counterpart to contain small but well dug in terrorist cells in the border region between the two countries. Since 2013, the Algerians have redeployed massively from the Moroccan to the Tunisia-Libyan border. That followed the unprecedented terrorist attack against the gas field of In Amenas, which speeded up an already massive retooling of the Algerian army. Germany has been the favourite arms provider, along with Russia, followed by Italy and the United States. Algeria knows all to well what the cost of terrorism is. Its political leaders badly mishandled its local version of the Arab Spring in 1988-92 and the resulting civil war cost the country dearly in destroyed infrastructure, capital flight, and hundreds of thousands of qualified people fleeing abroad.

Algeria’s relations with neighboring Morocco, however, remain frozen because of the unresolved status, in international terms, of the Western Sahara. Morocco has continued to modernize its economy, at it own steady pace, but its incapacity to find an imaginative solution to the Western Sahara issue prevents from acting together in a very troubled region the only two countries in northwest Africa which boast a functioning state, a well trained army and an active diplomacy.

Although the borders of the two countries remained closed, billions of dollars worth of smuggled goods flow from Morocco to Algeria and vice versa with the tacit complicity of the security forces. The situation would be funny were it not so sad—a comment on the incapacity of North African leaders more broadly to take the initiative, offer a vision of the future to their countrymen, and give North Africa a bigger voice in world affairs. As things stand, everybody buries their head in the sand—there is plenty of the stuff in the region. North African leaders and the media may be prone to conspiracy theories, but foreign actors are bound to play their own interests in a region where the local ones are incapable of doing so.

Francis Ghilès is an associate senior researcher at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs. He was the Financial Times correspondent for North Africa from 1981-95. He has contributed to the New York Times, Le Monde, El Pais, and others.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter