Egypt’s Revolution, Five Years On

More than ever before, it’s important to understand what we mean when we talk about the January 25 revolution.

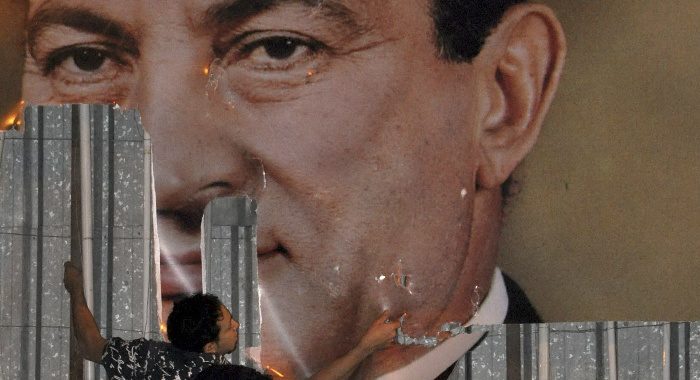

An anti-government protester defaces a picture of President Hosni Mubarak in Alexandria, Egypt, Jan. 25, 2011. Stringer/Egypt/Reuters/Corbis

On the fifth anniversary of the revolution, it appears defeated, broken, offering nothing but nostalgia for a time when Egyptian citizens dreamed of a democratic Egypt that offered them hope for dignity. The return of a police state, far worse than under Hosni Mubarak in terms of the sheer amount of injustices, brutality and abuses, adds insult to injury. Yet one thing remains clear: the social problems that caused the rupture in 2011 continue. Against all appearances, the revolution is not finished nor can it be written off.

Five years on, the regime offers an alternative narrative, one where the revolution is a conspiracy to destroy Egypt or an act of naiveté hijacked by “evil” forces. It’s the emperor’s new clothes. Their narrative is so flimsy it is does nothing but show up the regime’s absurdity. The battle for memory continues.

“Revolution” is not just a name we call the uprising on January 25. It’s a term of hope that says we might possibly be able to achieve more than the toppling of Mubarak. The mass awakening that followed was only a beginning. The revolution was not just the eighteen days of protests that toppled a president, but what started to take form in the months and years that followed. The revolution was, and is, an extended process that witnessed the awakening of many previously apathetic Egyptian citizens to the realities of how deep the regime’s corruption, repression, and awful criminality run within the veins of the Egyptian state.

The long period of upheaval, over the span of months and years, resulted in the participation of much larger segments in society directly in the revolutionary process. Many have been pulled into the revolutionary fight at different points along the way on account of monumental events such as the Maspero massacre, the clashes on Mohamed Mahmoud Street and outside the cabinet offices, or through more personal events, such as witnessing violence and injustice. Many joined the cause well after the initiating events of January 2011, but are in no way lesser “Januarians” than those brave few who made the calls and marched on Tahrir Square that first day.

The history of an extended revolution is not easy to wipe out, even if it is constantly manipulated. These smear campaigns include questioning the motivations of the revolution, slandering individual activists by spreading false news or airing private calls, or even attacking human rights. The regime has also tried to define the revolution as a set of protests and marches, rather than a moral position constantly adopted by its supporters in the face of injustices. However, the regime can no longer simply rewrite history through its limited state-controlled media. More than ever before, the authentic history is accessible through alternative media outlets.

The “Sisimania” that reestablished the regime’s iron grip on power is fading as all but the hopelessly deluded are taking steps back. The economy is in shambles as policy fails to address structural issues and corruption seems to be sponsored by the regime rather than fought. The backlash against the chief state auditor Hesham Geneina’s statements about the magnitude of corruption in Egypt is a prime example. When Geneina claimed that corruption cost the country billions of Egyptian pounds every year, government authorities reacted by accusing him of damaging the economy and defaming the state.

On this anniversary, the President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi regime is at its weakest, but that in no way means that the democratic and secular revolutionary dream will triumph. It simply means that Egypt is presently neither a stable democracy nor a stable autocracy. But political instability is not just a product of the state’s brutality. The international community continues to support the counter-revolution by supplying the present regime with aid, business, and weaponry, shrugging off rights abuses including forced disappearances in 2015.

This state of uncertainty, and political limbo, cannot last forever. Looking forward, it is more important than ever to understand and define the revolution. January 25 represents an identity that is neither Westernized nor Islamist, an authentic Egyptian identity that embraces universal values. Five years on defeated revolutionaries—dead, persecuted, locked up, slandered and abused—remain heroes to many. Revolutionary values were about truth irrespective of who spoke it, a fight against injustice no matter whom you fought, and a belief in the people’s right to determine their own fate through a democratic process. In Egypt, these values have existed long before January 25 and will continue to exist long after. No dictator has been able to eradicate them once and for all. And while there is no guarantee that dreams will become reality in Egypt, there is no turning back time.

Wael Eskandar is a freelance journalist and blogger based in Cairo. He has contributed to Ahram Online, Daily News Egypt, and Jadaliyya. On Twitter: @weskandar.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter