Nuclear Narratives

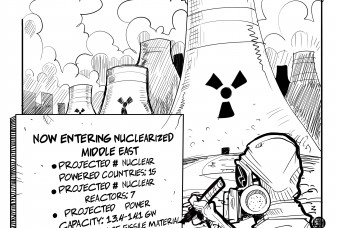

Western media coverage emphasizes how Iran is a threat to global security but rarely explores the more complex contours of the dispute. Are journalists once again fueling a dangerous showdown in the Middle East?

On September 27, 2012, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gave a presentation at the United Nations about Iranian nuclear capabilities. It featured a simplistic, cartoon-like drawing of a bomb and a hand-drawn “red line,” indicating that Iran’s accumulation of enriched nuclear material in excess of the amount represented by the red line would constitute justification for a military attack on Iran. Netanyahu did not mention any other option.

The Wall Street Journal’s coverage of the presentation focused on the differing official opinions about Netanyahu’s claim that “the international community needed to be prepared to attack no later than summer of 2013 to prevent Tehran from developing a nuclear bomb.” The New York Times coverage of the event focused on how Netanyahu’s deadline represented a “softening” of the Israeli position as part of a “difficult dispute with the Obama administration.” Britain’s Financial Times focused on divining Netanyahu’s motivation for the speech: “[The address] was a highly public argument for a stronger U.S. threat to attack Iran if it does not back off from what the Israeli leader described as the final push toward a nuclear weapon.”

Absent from much of the news coverage of Netanyahu’s presentation was a thorough evaluation of Iran’s actual nuclear capabilities, or of the full range of options available to policy makers. The news coverage made it seem as if the only choice facing the international community was when to threaten to attack Iran’s nuclear program, and what Iran needed to do to avoid being attacked.

The media coverage was representative of larger patterns we found in a study of the way in which six leading newspapers in the United States and Britain have framed events related to Iran’s nuclear program over the past four years. Rather than thoroughly exploring Iranian intentions and capabilities—and the factors affecting security strategy on all sides—much of the news coverage has focused on the political and diplomatic back and forth between government officials, particularly on what different American, European, and Israeli officials say and, more briefly, what Iranian officials say back.

Rather than asking why officials say what they say, and how best to settle the dispute on terms acceptable to all, news coverage—and as a consequence, public discussion—has been caught in a constrained and distorted narrative of how Iran threatens global security and how best to coerce it to stop. It is a narrative that has only a passing resemblance to the complex contours of the dispute, but one that holds vast and potentially dire consequences.

Echoing the Official Line

There can be little doubt that English-language news media coverage plays an important role in American and European public perceptions about Iran’s nuclear program and in the official policy response to it. Media scholars and political scientists have found that certain news outlets’ framing of the debate about Iraq’s supposed stores of weapons of mass destruction in 2002 and 2003 was found in hindsight to have profoundly affected public discussion of the threat posed by Iraq and increased the popular and political support for preventive military action.

With the international stakes as high, if not higher, in the case of Iran and its nuclear program, the question becomes how is news media coverage affecting public perceptions, and, ultimately, the policy options available to decision-makers? This was the driving question behind “Media Coverage of Iran’s Nuclear Program,” the study conducted by the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM). The study examined the news coverage of six prominent and agenda-setting English-language newspapers (the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post,Financial Times, Guardian, and Independent) during four three-week periods throughout the past four years.

In this instructive but admittedly limited sample of newspaper coverage of Iran’s nuclear program, many of the same patterns that plagued news coverage prior to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq reappeared: an overreliance on official government sources; a narrow framing of the dispute that hews closely to official preferences; and a lack of precision and context in discussing Iranian nuclear capabilities and intentions.

For example, nearly 70 percent of the sources quoted or relied upon in the 1,232 articles analyzed in the CISSM study were associated with a national government, with U.S. and Iranian officials making up 36 percent and 23 percent, respectively, of all government sources. As a consequence of this heavy reliance on official government sources, news coverage emphasized how officials saw the dispute and what officials argued was the preferred or necessary policy course.

The most prominent example of this pattern was the reporting about the Obama administration’s “two-track policy” of coercive diplomacy. Newspaper coverage of the 2009 Geneva negotiations and the subsequent fuel-swap deal focused on what officials from the United States and Western European states saw as the acceptable outcome of negotiations: Iranian concessions, including full cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and tight restrictions or prohibitions on Iranian dual-use nuclear capabilities. A September 27, 2009 Washington Postarticle reported that “[I]f Tehran does not respond seriously by year’s end [to U.S. demands], the United States and its partners could begin to push for crippling sanctions.” Similarly, an October 2, 2009 Wall Street Journal argued: “Despite initial signs of progress in talks… U.S. officials are expected to push for new U.N. or unilateral sanctions unless Tehran backs up its word with actions in coming weeks and months.”

When negotiations didn’t yield the expected outcome within the U.S.-imposed time frame, coverage focused on the necessity of sanctions to further pressure Iran. While some newspaper coverage focused on the likely inability of sanctions to produce Iranian concessions, few articles explored other potential policy options that might lead to a mutually agreeable outcome and avoid military action. Even fewer mentioned the possibility that pressuring Iran further could actually lead to regional instability or to an Iranian decision to build a nuclear weapon.

When the UN Security Council finally debated and passed an additional sanctions resolution in June 2010, the logic of the sanctions went mostly unquestioned in newspaper coverage. Instead, a majority of the coverage focused on the belief held by U.S. officials and others that the sanctions, in the words of a June 10, 2012, Washington Post article, “should prompt the Islamic Republic to restart stalled political talks over the future of its nuclear program.” Coverage during this period did give some attention to the failed diplomatic efforts of Brazil and Turkey to avoid the sanctions, but didn’t address the substantive critique made by Brazilian and Turkish diplomats of the sanctions resolution and the policy course adopted by the United States, China, France, Russia, the U.K. and Germany (the P5+1).

The news coverage examined in the CISSM study also lacked the necessary precision, context, and sourcing for assessments of Iran’s nuclear capabilities and intentions. Competing official and independent estimates and statements certainly made it difficult for reporters and editors to clearly describe Iran’s nuclear capabilities and intentions. But more often than not, coverage of Iran’s nuclear program simply included a restatement of some of the often-competing official claims. Rarely were the conclusions of all available estimates considered; and rarely were they synthesized sufficiently and put in the necessary context.

The February 2012 release of an IAEA report on Iran’s nuclear activities provided a window into how the newspapers covered this topic. The report noted that Iran had begun enriching uranium up to 20 percent U-235 in the Fordo enrichment facility and was enlarging its total stockpile of this type of uranium.

A February 25, 2012 Washington Post report was careful to characterize Iranian advances in uranium enrichment as moving Iran closer to having the requisite material to build a nuclear weapon, without suggesting that Iran had actually decided to build a weapon. The article did not acknowledge, however, that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), to which Iran is a party, does not prohibit non-nuclear weapon states from enriching uranium up to 20 percent U-235 or limit the amount of such material they may have for peaceful purposes, such as fueling a research reactor or producing isotopes for medical use, so long as these activities are under IAEA safeguards. Instead, the report focused on the degree to which Iran’s activities moved it closer to having enough low enriched uranium and centrifuges to be able to produce a weapons’ worth of highly enriched uranium in a relatively short amount of time, should it choose to do so, and in the likelihood that the “advances” in Iran’s enrichment program were in excess of what Iran needed to meet its stated goals.

Other coverage of the IAEA report was less nuanced, instead using less precise language about Iran’s “nuclear ambitions” and simply presenting Iran’s claims and U.S., European, and Israeli suspicions about Iranian nuclear activities: “New suspicions over Iran’s nuclear ambitions emerged Friday,” reported a February 25, 2012 Wall Street Journal article. “Iran has dramatically accelerated its production of enriched uranium in recent months while refusing to cooperate with an investigation of evidence that it may have worked on designing a bomb,” a February 25, 2012 Guardian report read.

The approach of this coverage reflected the efforts of competing governments to frame public understanding of the policy choices confronting officials. While U.S., European, and Israeli officials often had varying assessments of Iranian capabilities and intentions—and varying preferences for how to address what they perceived to be the threat posed by Iran—all understood the basic dynamics of international diplomacy and domestic politics: portraying Iran’s advances as evidence of dangerous intentions and growing capabilities to make weapons, as some of the coverage of the IAEA report did, made it easier for officials to advocate for a more urgent response to Iran’s nuclear activities, possibly including the use of military force. Putting Iran’s advances in the context of previous assessments, as some of the articles did, left open the possibility that additional coercive measures or diplomacy could succeed in thwarting Iran’s nuclear advances.

Questioning Iran’s Intentions

Other characteristics of news coverage of Iran’s nuclear program included the degree to which coverage placed on Iran the burden for resolving the dispute over its nuclear program, and the manner in which negative sentiments about Iran colored newspaper coverage.

Coverage of the September 2009 revelation of the existence of the Fordo enrichment facility provided a clear example of how newspaper coverage framed Iran as fully responsible for causing the dispute, and therefore fully responsible for the concessions necessary to end it. The coverage acknowledged that U.S. and European leaders were using the construction of an undeclared centrifuge facility at a hardened site near a military base as leverage in upcoming negotiations with Iran, but it gave little consideration to Iran’s claim that it had done so in response to foreign threats to destroy its less protected centrifuge facility. A September 26 Guardian article explained how U.S. and European leaders saw the Fordo revelation as an opportunity to “demand” that Iran take “concrete steps to restore ‘confidence and transparency’ in the country’s nuclear program.” In other words, according to the coverage, the negotiations were exclusively about Iranian behavior—what it was willing to do and not do. As a consequence of its failure to disclose the site earlier, Iran did bear some responsibility; but to place the entire burden on Iran is to ignore a tumultuous history of past negotiations and actions about which all parties have felt aggrieved, and of the well-established tenets of the non-proliferation regime.

Coverage of the negotiations that followed the Fordo revelation referred regularly to the hope that pressure on Iran would force it to engage in “serious negotiations.” However, the coverage did not describe in any detail what behavior would demonstrate that Iran was “serious” about negotiations and how such behavior would differ from previous behavior. Indeed, at times it seemed that “serious negotiations” was a euphemism for conceding to U.S. demands. The coverage never questioned whether the United States or the P5+1 was doing enough to convince Iran that it was serious about seeking a negotiated resolution on mutually acceptable terms, or how American interests and domestic politics constrained Washington’s policy approach.

When the negotiations yielded agreement in principle on a deal for Iran to swap much of its stockpile of low-enriched uranium for fully manufactured nuclear fuel using uranium enriched outside of Iran, newspaper coverage was cautious, focusing on the potential benefits of the deal if Iran would quickly accept specific terms of the U.S. proposal to prove that it was not just “playing for more time.” As an October 2 Wall Street Journal article noted, “Iranians may be seeking to defuse pressure for sanctions while continuing their nuclear program.” A Financial Times article from the same day was considerably more skeptical: “A deal remains a long shot. At stake is whether Iran builds a nuclear infrastructure that, despite all its protestations, would make it much easier to produce fissile material for a bomb.” None of the coverage questioned whether it was necessary or productive to demand that Iran quickly take or leave the deal, at a time when internal politics prevented Iranian leaders from making a quick decision.

Again, the point is not that Iran is blameless and undeserving of suspicion, but that there are complicated international and domestic contexts to the broader dispute that need to be acknowledged. Indeed, if these contexts are understood fully, one would appreciate the degree to which Iran has equally significant reason to be suspicious of U.S. and international motives and behavior. For instance, the United States has a significant and active military presence in the Middle East, Persian Gulf, and Afghanistan, and together with Israel, the United States has been waging a covert campaign to forcibly undermine Iran’s nuclear program.

The generally prevalent negative sentiments toward Iran are most clearly seen when coverage of Iran is compared with international responses to similar events and behavior by other countries. A September 26, 2009 Independent article published a day after the Fordo revelation contrasted calls to lift economic sanctions against Burma with calls to further sanction Iran and suggested that this “double standard” might be Iran’s fault because it is “a particularly difficult country to deal with,” and because “its ambitions and its willingness to compromise are so uncertain.”

Negative sentiment toward Iran was also pervasive in 2010 coverage of the public debate about imposing another round of punitive sanctions against Iran. Iran’s behavior was characterized as sneaky: “Iran and its state-backed enterprises have become adept at skirting sanctions,” read a June 10, 2010 Independent article; “a shadowy network of Middle East gasoline suppliers is already undermining U.S. efforts to pile pressure on Tehran,” read a June 17, 2010 Wall Street Journal article.

While Iran might indeed have developed sophisticated ways to get around UN and national economic sanctions, that could be because it views the sanctions aimed against it as illegitimate and part of a campaign to weaken the government and interfere in the inner-workings of the country. Moreover, the Iranian government and the Iranian people may see the ability to circumvent sanctions as innovative or resourceful, not merely evasive, but none of these alternative interpretations was explored in news media coverage of this issue.

Differences in newspaper coverage of Iranian and Israeli ballistic missile tests also demonstrated underlying sentiments about Iran. In the days leading up to the October 2009 Geneva negotiations, Iran test-fired a few types of ballistic missiles and coverage of these tests focused on the degree to which the events were meant to send a belligerent message to U.S., European, and Israeli officials prior to negotiations. According to a September 29, 2009 Independent article, the Iranian missile tests were a “show of defiance.” This report also emphasized the offensive capabilities of the tested missiles and the fact that their capabilities put Israel within range.

In contrast, when Israel was set to test-fire missiles as part of its anti-ballistic missile program development in early 2012, the emphasis of newspaper coverage was on the missiles’ defensive capability rather than whether its actions provoked concern. Underlying this coverage is the assumption that Iranian missile capabilities pose a threat, while Israeli capabilities are non-threatening and justified. While this could be the case, it’s also possible that Iran’s security strategy rationally justifies its missile capabilities and that Israeli capabilities are threatening to some.

Another aspect of newspaper coverage that could be seen as revealing underlying sentiments about Iran is how frequently Iran is referred to as an “Islamic republic.” The newspapers in this study rarely referred to Iran by its formal name, the Islamic Republic of Iran, on first mention, instead simply referring to the country and its government as “Iran.” Yet on second mention, newspapers regularly referred to the country and the government as “the Islamic republic.” Iran is a theocracy, where Islam is a central part of governance and society, yet in using this alternative term, news outlets implied that Iran’s Muslim identity made it different—and potentially more threatening—than other countries. By comparison, although the formal name of Pakistan is the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, it is rarely if ever referred to by these newspapers as the “Islamic republic.”

Informed Public Discussion?

None of the patterns that were found in recent newspaper coverage of Iran’s nuclear program were terribly surprising. Media scholars and observers have long hypothesized and experimentally confirmed that reporters and editors tend to index their news coverage of foreign policy events to official viewpoints and that public discussion about policy options tends to be limited by the scope of official preferences. News media also have a well-documented tendency to portray “out” groups, such as communists during the Cold War or Muslims after the September 11 attacks, in negative or at the very least suspicious ways. A 2007 study by scholars at Louisiana State University confirmed that the same is true regarding portrayals of Iran and Iranian officials in some coverage of Iran’s nuclear program.

The effects of these tendencies, however, have varied with the nature of events. Sometimes they lead news media to inform public discussion in a way that eventually feeds back into official discussion; sometimes they simply affect official discussions, which are then recycled by reporters and editors who rely predominantly on official sources. Sometimes sentiments presented in news coverage influence public sentiment; and sometimes they simply reinforce already-held public sentiments. In English-language news coverage of Iran’s nuclear program and the outcome of the international dispute about it seldom are these tendencies sidestepped altogether. Journalists rarely seem to find a way to inform public discussion with opinions and policy ideas from outside of official circles, which could then inject new perspectives and possibilities into official debates.

The tendency of some news media to rely so heavily on official sources and to adopt the framing of U.S. and European government officials leads to a focus on official conceptions of the threat posed by Iran’s nuclear program and on official preferences for how to deal with it. Again, while there is variation in official U.S., Israeli, and European policy circles about the threat posed by Iran and how to confront Iran’s nuclear program, the baseline view is that Iran’s known nuclear capabilities, its unreasonable and ideological disposition, and its past interference in regional affairs pose direct threats to U.S., European, and global interests in the Middle East. To address this threat, the international community needs to pressure Iran—with economic sanctions or threats of military attack—to restrict its nuclear activities. Much of the news coverage examined in the CISSM study reflects and reinforces these official views.

Indeed, Iran’s nuclear program is worthy of international scrutiny; some questions about past Iranian research related to nuclear weaponization remain unresolved. But why is the threat posed by Iran’s nuclear program, which by all accounts has not actually developed nuclear weapons, seen so differently by officials than the threat posed by a North Korean regime that has built and tested nuclear weapons? Why can the United States and its international partners be satisfied with patiently and vigilantly limiting the nuclear threat from North Korea but not Iran? Is the threat posed by Iran made larger or smaller by the coercive diplomacy and punitive economic sanctions that have been the dominant approach advocated by U.S., European, and other government officials? These types of questions, which leave room for alternative conceptions of the threat posed by Iran and how to resolve the ongoing dispute, are often overlooked as news media focus primarily on official pronouncements and framings.

The news coverage examined also tended to marginalize public opinion, especially if it was skeptical of official narratives. For instance, official policy discussions about Iran’s nuclear program in February and March 2012 as captured in news coverage, focused on the possibility and rationale for Israel and/or the United States to attack Iran’s nuclear infrastructure in order to impede its nuclear program. Meanwhile, public opinion in the United States and elsewhere showed a considerable reluctance to attack Iran. Only 25 percent of Americans surveyed in a March 2012 Program on International Policy Attitudes poll supported an Israeli military attack against Iranian nuclear installations, while more than 74 percent of respondents thought the United States should work through the UN Security Council, presumably by engaging a broader set of stakeholders, to achieve a peaceful resolution. More recently, a June 2013 New York Times/CBS poll found that nearly 60 percent of Americans surveyed believed that the threat posed by Iran could be contained—nearly the same number that felt that the threat from North Korea could be contained. These sentiments were rarely represented in news coverage during the periods examined. These patterns point to an important incongruity: while newspaper coverage constrains public and official discussion, the public doesn’t always buy the official line.

The tendency of some English-language news coverage to place on Iran the burden to resolve the dispute about its nuclear program also significantly constrained policy and public discussions. Identifying the appropriate policy course depends on whether one sees the failure to resolve the dispute as a result of Iranian intransigence and unwillingness to engage in “serious negotiations,” or as a consequence of the P5+1 trying to apply inequitable rules on the use of nuclear technology and materials. If the latter were the case—and this is not the majority opinion among U.S., European, Israeli, and other officials and as a consequence was rarely expressed in news coverage—then resolving the dispute might require the P5+1 to assure Iran that it would not be kept from or punished for engaging in activities protected by international law. Similarly, if what is perceived and reported as Iranian intransigence or lack of sincerity is seen instead as a reasonable Iranian response to what Iranian officials view as threats from Israel and the United States, then P5+1 policy makers are foolhardy to wait for Iran to agree to terms that could institutionalize what it views as a strategic disadvantage.

Perhaps most troubling of all of the patterns identified in the study is the tendency to associate negative sentiments with Iran. If policy makers or members of the public perceive Iran as implacably hostile toward some of its neighbors, other actors, or the international system as a whole, or as preternaturally untrustworthy—as some of the news coverage examined suggests it is—then it will be that much more difficult to conceive of and execute a consensual resolution to the dispute.

If the goal of news media is to act in the public interest, to hold public officials accountable, and to permit an informed public to play a constructive role in the foreign policy decisions made by their governments—in their name—then journalists ought to consider more carefully how they go about framing the facts and assessments that animate complex policy issues such as Iran’s nuclear program and how the international community could and should respond. Without considering these fundamental characteristics more carefully and reflecting a broader spectrum of viewpoints and policy possibilities in their coverage, they are liable to repeat the mistakes that contributed to disastrous policy choices in the past.

Jonas Siegel

Saranaz Barforoush is a PhD student at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland. From 2002 to 2008, she worked as a reporter and translator for Iranian newspapers and weekly magazines, including Hamshahri Daily, Asr-e-ertebat, Zanan, and Hayat-e-no.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter