Crisis of Identity

Europe’s social and economic order fundamentally changed with the end of the industrial era in the 1970s. The resulting tensions led to an identity crisis, as minorities sought to address injustices and nationalists agitated against cultural and religious diversity. Is multiculturalism now destined to fail?

Far-right protesters carry banner reading “No Islam in Poland,” Warsaw, April 20, 2016. Franciszek Mazur/Agencja Gazeta/Reuters

Over the past half-century, across the entire world, the identity question has replaced social issues in the public debate. The nation, cultural differences, ethnicity, even race and religion—and especially Islam—have stoked passions and terrible tensions within numerous countries, between nation-states, and on a global scale. Meanwhile, we talk far less about the social exploitation of workers or the class struggle.

In Europe, and particularly in France, this change, as the anthropologist Marcel Mauss would say, is a total social fact. It lays the parameters for public debate and constrains the way we think about almost any social, political, or even economic issue today. In order to understand how this total social fact dominates society, in an almost coercive fashion, we have to understand the background factors first.

The social and economic order fundamentally changed from the beginning of the 1970s. The industrial era ended, as did its forms of management and methods of organizing workers—beginning with Taylorism—and the structural conflict opposing the workers’ movement and owners of labor from the workshop to the factory.

A major consequence of these changes was the declining need in Europe’s heavy industries for non-qualified labor, many of whom at the time were migrant workers originally from Arab and often Muslim countries living in France, Belgium, and Germany (where they were called Gastarbeiter, “guest workers”). As a result, many of these workers, who were called upon to stay in Europe along with their wives and children and integrate into society, were confronted by major difficulties: unemployment, diverse forms of social insecurity and exclusion, racism, discrimination, family destabilization, and the poor education of their children. Within these populations there developed a new emphasis on religion, most often Islam, but also sometimes variants of Protestantism.

The growth of Islam in Europe is, essentially, the result of excluded peoples looking for a place in their new countries. They wish to have a decent life, educate their children, and obtain a degree of social mobility. But this form of religious identity can take on radical, and sectarian, aspects. In addition, the option of religion—resuscitated by an Islam in Christian lands—has been able to seduce, and will continue to seduce, young people looking for meaning, even if they are not from immigrant or Muslim-origin backgrounds. This is how terrorism linked with radical Islamism has obtained currency in Europe, and why it includes both those who come from immigrant backgrounds and have not been able to find their place in society, and others who want to give some sense to their life. These people are ready to join the fight against dictatorial regimes in foreign countries and serve a cause that, at the outset, they perceive as humanitarian.

The reference to a collective identity is the result of the journey, and a process of individual subjectification, de-subjectification, and re-subjectification. That identity is not necessarily there to begin with. Actors do not join a living and pre-existing community to which they belong, but refer to an imagined community, the nature of which becomes clear, for them, along the way. Radicalization, as the political scientist Olivier Roy has shown, can come before Islamization. And contrary to popular perception, the phenomenon owes more to modern individualism than belonging to a collectivity. Actors make the choice, at one time or another, to join the community, and this choice is personal, singular, and that of an individual.

Yet the growth of identity issues in Europe, and especially in France, does not only concern young people of immigrant backgrounds. It concerns many kinds of minority groups that have evolved or solidified over the past fifty years within Western societies. From the late 1960s, regionalist movements—sometimes secessionist—developed within countries like Spain (in the Basque region and Catalonia), Northern Ireland, Italy (in Sardinia, and later the country’s Northern League), Belgium (the far-right nationalist party Vlaams Blok in Flanders, which became Vlaams Belang in 2004), and France (the Breton, Occitan, and Corsican movements, among others). These minority movements connected, and in some cases still connect, their identity with a territory that they wish to emancipate or liberate.

Other actors, operating in the same historical context, have put forward claims arising out of a collective past, and demanded recognition of their identity, independent of any territorial issues. In France, Jewish and Armenian populations with painful memories have demanded, since the 1970s, recognition of their historical sufferings, including the French state’s role in the deportation of Jews, or the fact that Armenians were victims of genocide (and not just mass killings, as Turkish authorities claim). Later, a diversity of movements among people of black African origin put forward a post-colonial identity highlighting the injustices of the colonial era: slavery, racism, and exploitation of the colonized.

Consequently, different minority groups—new and old immigrant communities, and other minority populations claiming a long past in Europe, whether real or mythical—opened up a process in the late 1960s and early 1970s which has thrown into doubt the capacity of European nation-states for integration and assimilation.

At the time, these political challenges happened in a context of strong economic growth, almost full employment, and confidence in progress and science. They occurred at a domestic level, and were not international or “global,” even if they emerged at roughly the same time in relatively similar fashion, and sometimes had connections with other (especially diaspora) movements.

Beginning mostly in the 1980s, a third kind of identity politics reemerged on the scene: nationalist parties, which though they did not completely disappear after the Second World War had hitherto been extremely marginal.

The historical idea of the nation begins, in modern times, in the seventeenth century, if not earlier. At moments it has accompanied progressive, emancipatory movements—notably during the “springtime of peoples” in 1848, the nationalist revolts which spread hope across Europe. But, in the last decades of the twentieth century, the nationalist idea became the quasi-monopoly of political forces swinging between the extreme right and populism. Some researchers label these political formations “nationalist populism,” which calls for the self-isolation of societies and develops an image of national homogeneity that is, more or less, racist, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic. Identity is the basis for their political action, which in some cases is openly violent, as with Golden Dawn in Greece.

Other actors prefer to develop a strategy bringing them democratic access to power via elections. In these cases—such as France’s National Front—violence comes from an extreme right that the National Front is unable to control and is dominated by neo-Nazis and skinheads, for example, who merely by existing in the public space gain a certain legitimacy to act.

Failure of Multiculturalism?

An important consequence of the rising power of the radical right—nationalist and nationalist-populist—is the change it imposes on the broader political landscape. On the one hand, large segments of the traditional and conservative right are moving into line with the radicals, at least ideologically, if not politically. That is how national identity has become a central element in the public debate. The traditional right, and even the left, proposes or undertakes policies to promote national identity, usually in a way targeting, openly or implicitly, immigrants, Arabs, Muslims, and on occasion Gypsies or blacks. Alongside cultural, even religious and racial, fragmentation, social and political tensions have moved the identity question to the forefront in France, as across Europe.

These tensions influence many different aspects of the public debate. To some extent, the debate opposes two sides: on the one hand, those supporting an open society who are not afraid of otherness and the broader world, and favor the European project (what the sociologist Ulrich Beck calls “methodological cosmopolitanism”). On the other, partisans of a closed nation, anti-European, “sovereignist,” generally hostile towards cultural and religious diversity, and more or less racist—what Beck calls “methodological nationalists.”

But the debate cannot be reduced entirely to such an elementary juxtaposition. It also takes the form of a conflict between supporters of multiculturalism—institutional arrangements that recognize, to some extent, different cultural identities—and opponents who only wish to recognize “individuals” within the public space. The multiculturalist camp encountered limited success in the 1990s, but has become more and more weak since the early 2000s, especially following the terrorist attacks in London (July 2005) and in Paris (January and November 2015). Multiculturalism is now accused of having “favored” Muslim communities and, therefore, having allowed for the spread of a radical Islam that produces, or seems to come with, terrorism.

Within the space of a few weeks in 2011, British Prime Minister David Cameron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and French President Nicolas Sarkozy used almost the same words to announce the failure of the multicultural model. For the most part, they were referring to Muslims and immigrants, which betrayed a terrible semantic imprecision on their part. Islam is a religion—and not a culture—and most immigrants define themselves foremost as individuals who have left their country to live in another. For them, cultural and religious questions come second. Without those two issues—the role of Muslim religion and migrant policies—the famous discourse around “multiculturalism” falls flat. There would be nothing left to discuss, besides issues around sexual (and homosexual) identities.

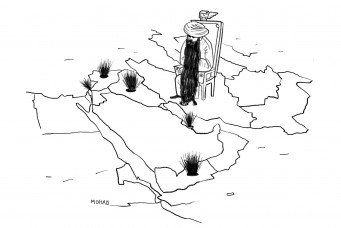

Today, the deepest anxieties about identity center on Islam, which is itself an identity, and migrants, which does not count as one. The debate pits those who envision a respectable place for Muslims in European society alongside the dominant Christian religion, against those who wish to weaken Islam, stop it from flourishing, and keep it in “its place.”

What is the nature of Islam and Muslim identity? The debate here opposes, above all, those believing in the replication of an existing and unchanging identity, and those seeing that identity as an invention, as an ongoing process through which religion renews itself. In our globalized world dominated by a few large religions, Islam in Europe is constantly suspected of being dependent on foreigners, and owing too much to the political support of states like Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, and their role in training imams or paying for the construction of new mosques. As a result, the religious identity of Muslims is perceived to be a threat for the majority identity group and its culture, language, traditions, and religion—even the totality of its cultural and historical being.

At a time of grave difficulties in Europe—when the continent is suffering from a financial and economic crisis, anti-European Union movements in countries like Greece and the United Kingdom, and the migrant crisis—there is an enormous risk that countries will begin closing in on themselves, calling upon the “nation” and, simultaneously, denouncing or casting suspicion on other identities as subverting their “national” identities and cultures. It is no longer clear, in such a stormy context, whether religious and cultural questions arise independent of social ones, or whether they are pushed to the forefront when no one knows anymore how to solve social inequality, unemployment, and the breakdown in economic growth.

The identity debates are a sign of a new era where these issues have become, again, unavoidable. Europe has not forgotten its wars of religion, or the major military and nationalist clashes of past centuries; the resurgence of identity issues expresses the continent’s impotence in the face of its social and economic ills.

Translated from the French by Amir-Hussein Radjy.

Michel Wieviorka is a professor at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales and CEO of the Fondation Maison des sciences de l’homme. He was president of the International Sociological Association from 2006 to 2010 and director of the Centre d’analyse et d’intervention sociologiques between 1993 and 2009. He is the founder and editor of the journal SOCIO and was co-director of the journal Cahiers internationaux de sociologie from 1991 to 2011. He is the author of numerous books including Le Séisme; Retour au sens: Pour en finir avec le déclinisme; L’antisémitisme expliqué aux jeunes; and La violence. On Twitter: @michelwieviorka.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter